Coal remains a key fuel for the power industry and metal making. Pressured by the “green” agenda, the developed economies that placed utmost importance on environmental priorities, especially in the European Union (EU), have become much less dependent on the fuel in the last 10 years. The developing economies, including India and China, which are desperate for affordable energy, do not reduce their consumption but rather plan to build new coal-fired power plants through 2030. In 2021 and 2022, the global energy crisis triggered by sanctions against Russia and a hike in gas prices has brought coal back to the agenda of leading European powers, too.

This review comes first in a series of three publications on the future of coal in Russia and worldwide: Russian Coal Market, Global Coal Market, and Russian Coal Export Potential. The publications will present an analysis of the status and a forecast of sector development through 2050.

Russian coal production status: in defiance of sanctions

The coal industry has special significance for Russia notwithstanding a notable decline in coal consumption by the power sector. In particular, coal accounts for approximately 12–13% of power generated in Russia and the revenue from international sales provides about 4% of contributions to the national budget from the export of goods.

Based on 2022 data, the Russian coal industry has demonstrated high stability and adaptiveness on the back of the sanction restrictions imposed by the EU and some other countries. The domestic coal production did not decline and even showed a symbolic growth reaching 443.6 mln tonnes, as reported by Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak in mid-February 2023. For reference, the Russian coal output of 2021 was 438 mln tonnes. The stable production was provided, among other things, by supplies to the domestic market, which grew by 12.2%.

How thermal coal differs from metallurgical coal

Thermal coal is used as fuel for thermal power plants due to its physical properties. Metallurgical coal provides more intense and longer burning due to a higher calorific value (heat of combustion), so it is used for steelmaking. A distinctive feature of metallurgical coal is the presence of vitrain, which at a high temperature (1,000–1,100oC) can melt and acquire a feature of baking into a dense mass – coke. The latter is used in blast furnaces to make steel. Due to different physical properties, the two types of coal have different consumers – the power industry and steelmakers, and the demand depends on different drivers. About 75% of global output is thermal coal and only about 15% is metallurgical coal. The remaining 10% is lignite (young brown coal with a high content of water and low calorific properties)

Thermal coal demand outlook

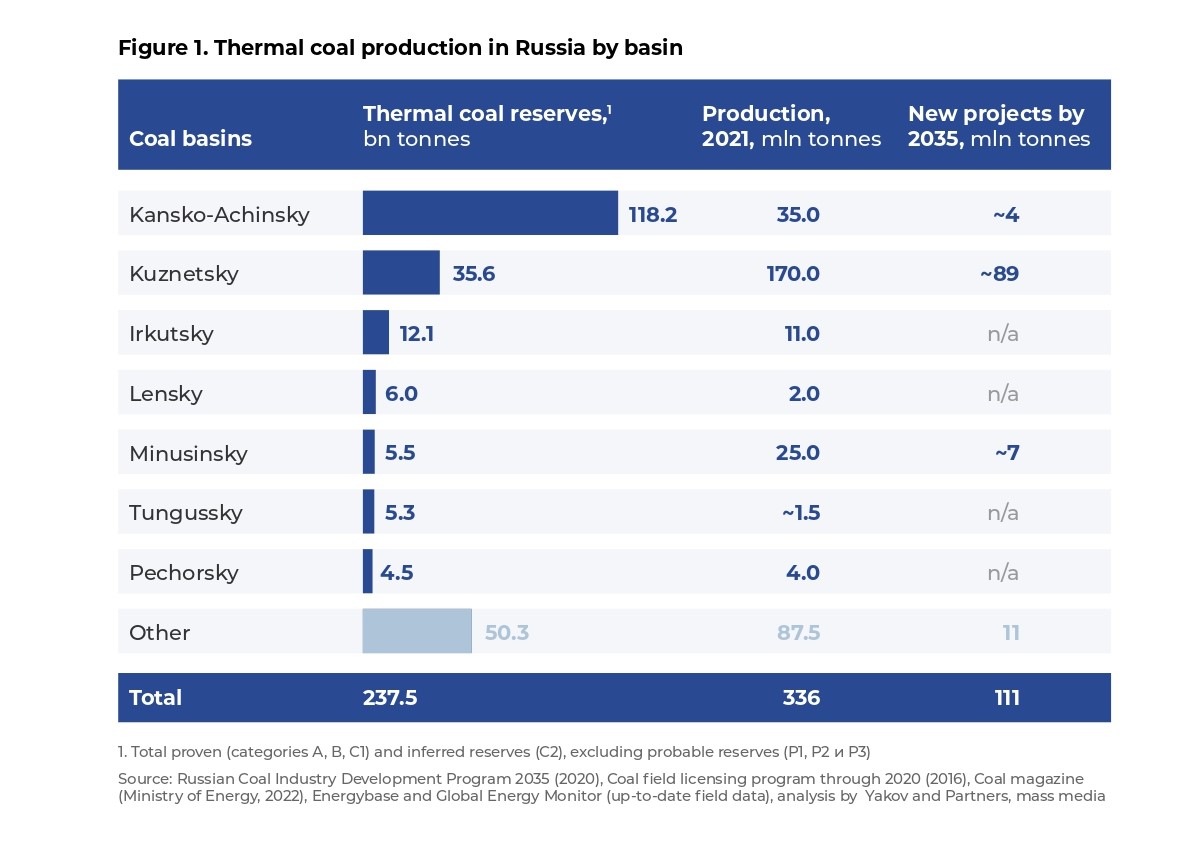

As of today, Russia is fully supplied with thermal coal for the next several hundreds of years. The booked reserves (Categories A, B, C1 and C2) of Russian coalfields are 238 bn tonnes. About 70% of that amount is related to three largest coal basins: Kansko-Achinsky, Kuznetsky, and Irkutsky (Figure 1). The cost of production generally fluctuates from USD 44 to 70 per tonne with up to USD 103 per tonne in Tungussky basin. There are also plans to develop new fields in Kuznetsky, Kansko-Achinsky, and Minusinsky basins.

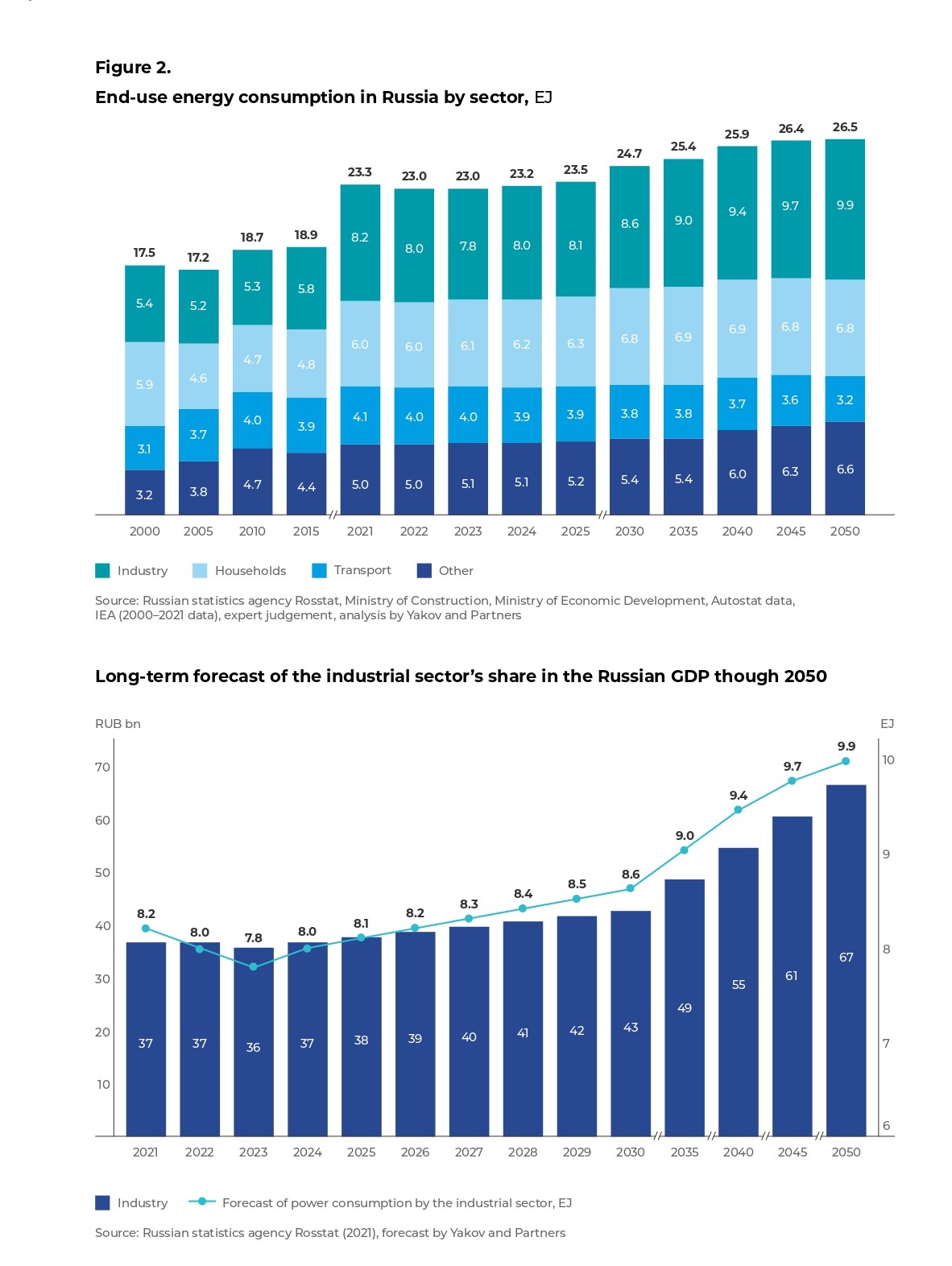

To analyze the situation in the coal industry, we have built three development scenarios: Base Case, Accelerated Transition, and Recession. Under the most probable base case scenario, we forecast that, by 2050, Russian power consumption, which determines the demand for thermal coal, will increase to 26.5 exajoules (EJ), which is 15% higher vs. 2022 (Figure 2). This will be mostly driven by the industrial sector. Subject to a preserved share in the GDP, by 2050, the industrial output will be approximately RUB 67 bn measured in 2022 money, and power consumption will grow to 9.9 EJ vs. 8 EJ in 2022.

The industry, transport, and households will actually provide 85% of power consumption in total. While the industry consumption will grow steadily by 2.1–2.6% per year in 2024–2050, the transport sector consumption, on the contrary, will decline by 0.9% per year on average. The trend is explained by slow growth of the Russian vehicle fleet and wider use of more energy efficient electric vehicles starting from 2030. In our estimation, on the back of withdrawal of international brands from Russia, the fleet will shrink by one million vehicles by 2025 and will not return to the previous size until 2029. At the same time, subject to vehicle supply recovery, we forecast higher annual average rates for Russian vehicle fleet growth in 2030–2050 – by 0.8%. Power consumption by households will grow by 1.4% on average each year until 2030, inclusive, but then the trend will reverse on the back of the declining population, so since 2030 the consumption will start dropping by 0.1% each year. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in the 2010s, Russia was among the countries with the highest per-capita power consumption by households. Subject to housing growth, per-capita power consumption will keep increasing and, in our estimation, will most likely reach 19 MWh per person per year by 2050.

Gas and oil prevail

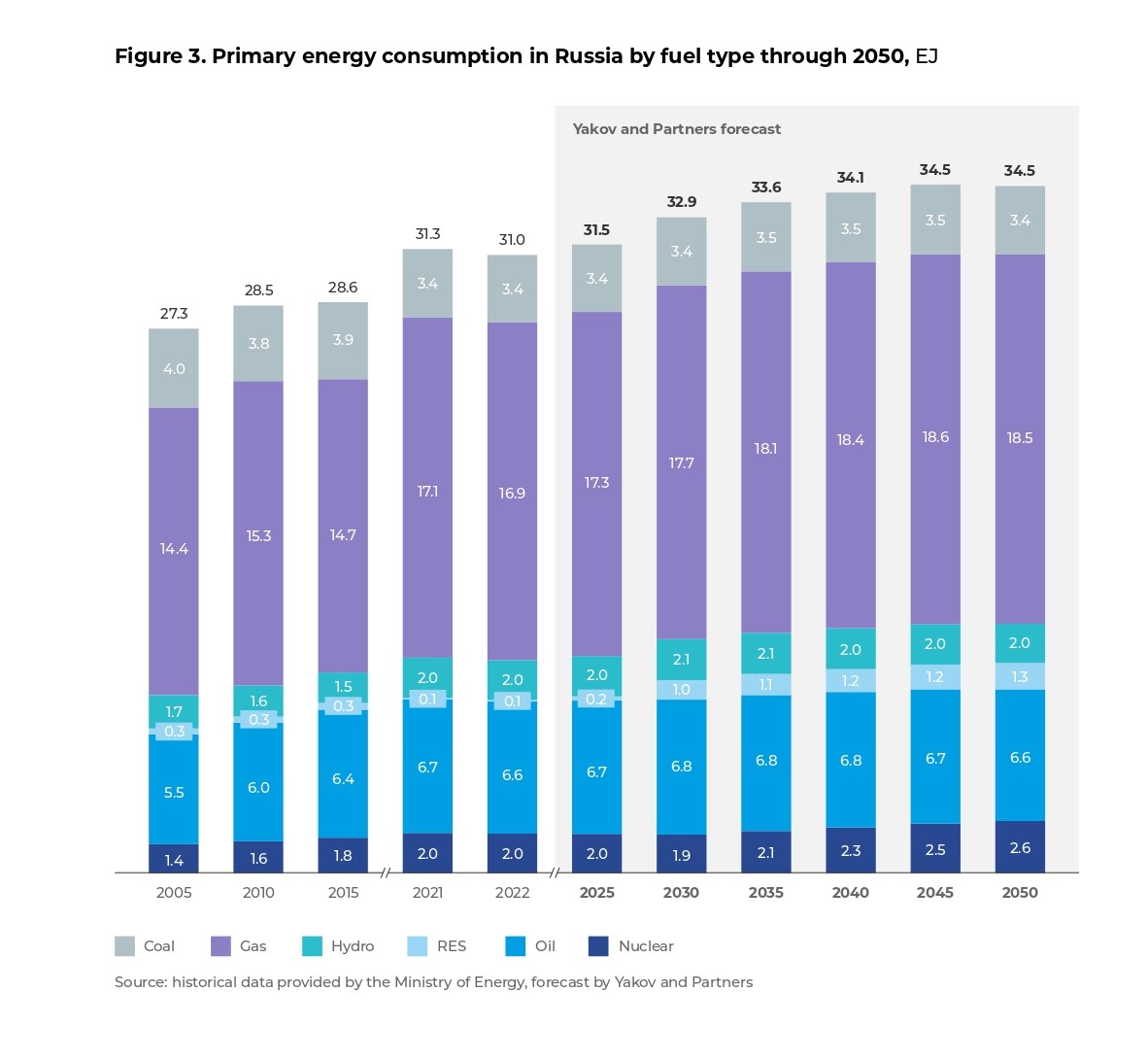

In Russia, more than 70% of primary energy consumption (which includes all energy – from renewable and nonrenewable sources – to conversion to power and heat) is associated with oil and natural gas, which is explained by rich reserves of the minerals, their low production cost and extensive infrastructure for production and transportation. In our projections, Russia’s primary energy consumption will amount to 34.5 EJ by 2050. At the same time, the share of thermal coal in the total primary energy consumption will go down from 11% to 10% (Figure 3).

The lower share of coal consumption is due to lower efficiency and high capital expenditures per 1 MWh of nameplate capacity of coal-fired power plants compared with gas-fired ones. As of 2022, the LCOE (levelized cost of electricity) for coal was USD 91/MWh vs. USD 45/MWh for gas. By 2050, in our estimation, the LCOE may go down to USD 61/MWh for coal and up to USD 51/MWh for gas.

Even with current high prices for fossil fuels, natural gas (combined cycle) and coal will remain the cheapest sources of energy in Russia through 2050. The development potential of renewable energy (RE), such as solar and wind power, will be limited in Russia as it is less stable due to weather dependency and has a high LCOE (the current figures range from USD 135/MWh to USD 214/MWh). Even though the RE production cost is projected to go down to USD 101–126/MWh, the LCOE for fossil fuels will still be much lower through 2050.

The share of renewables is expected to increase specifically to replace the declining share of coal in the energy balance. Considering the existing externalities, however, the Russian Ministry of Energy, in our estimation, will hardly be able to realize their plans to grow the share of renewables in the energy balance to 10% by 2050. Among environment-friendly sources, nuclear fuel and hydropower (HPPs) will keep their share in the consumption.

Metallurgical coal demand outlook

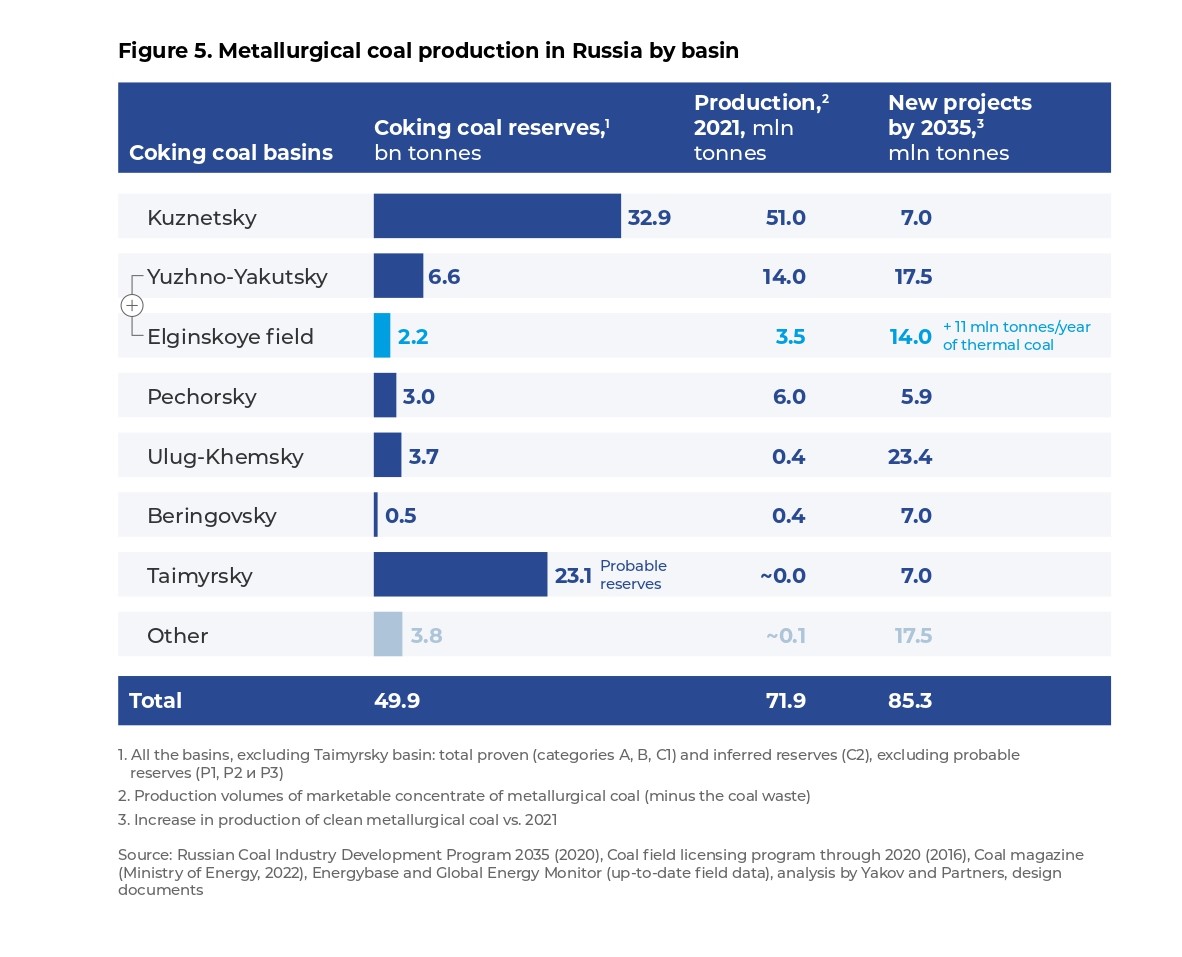

Russia’s output of metallurgical coal has been stable for many years in a row. The key supplier to the domestic market is Kuznetsky basin (74% of the output); there are plans to develop Ulug-Khemsky basin in an active manner and intensify the development of Russia’s largest Elginskoye field of metallurgical coal with reserves (Categories A, B, C1 and C2) that were previously estimated at 2.2 bn tonnes. For reference, the total reserves of four key basins of metallurgical coal (Kuznetsky, Yuzhno-Yakutsky, Pechorsky, and Ulug-Khemsky) are estimated at approximately 46 bn tonnes. The cost of production is USD 45–65 for a tonne. Under the Russian Coal Industry Development Program 2035, it is planned to launch investment projects to expand production to 100 mln tonnes per year in East Siberia and the Far East.

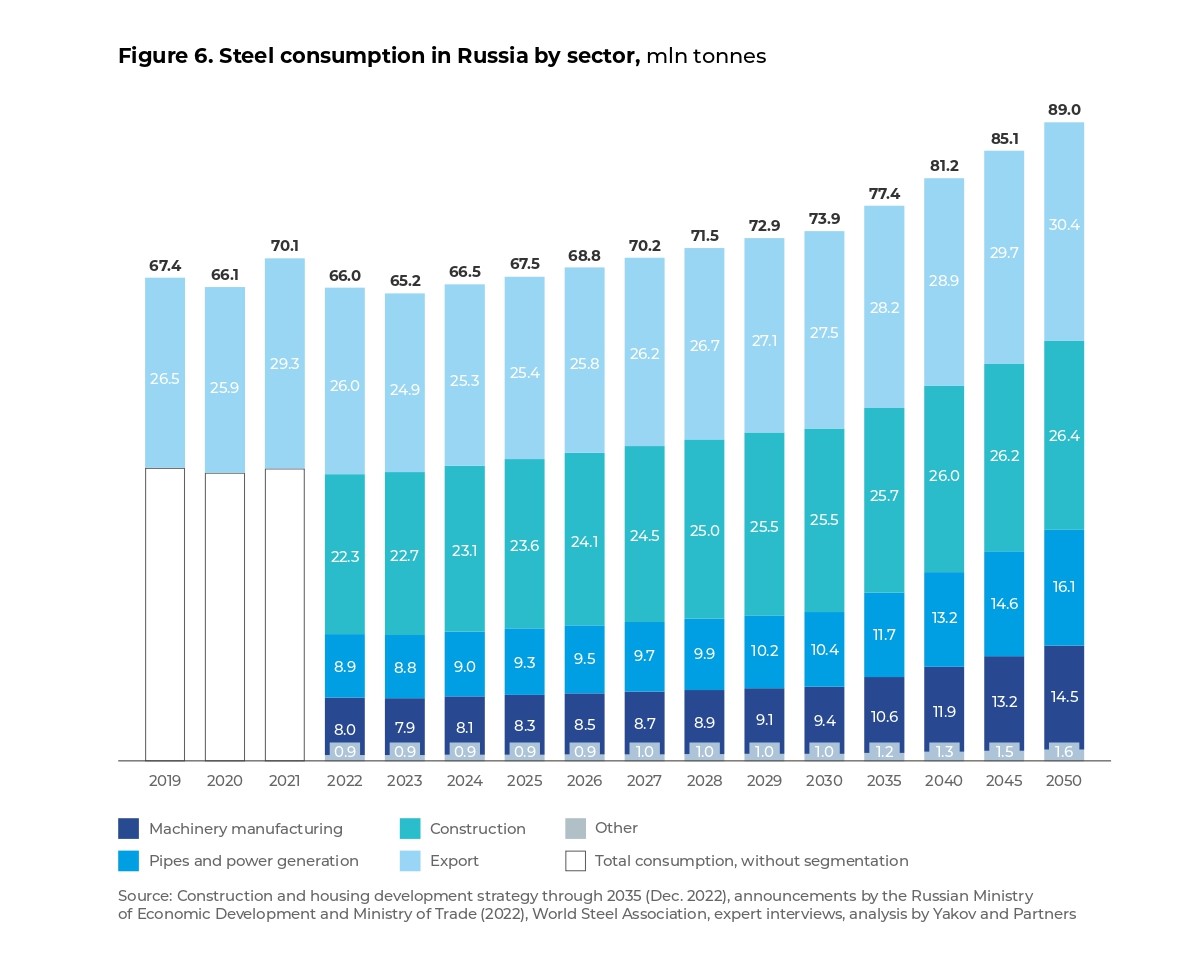

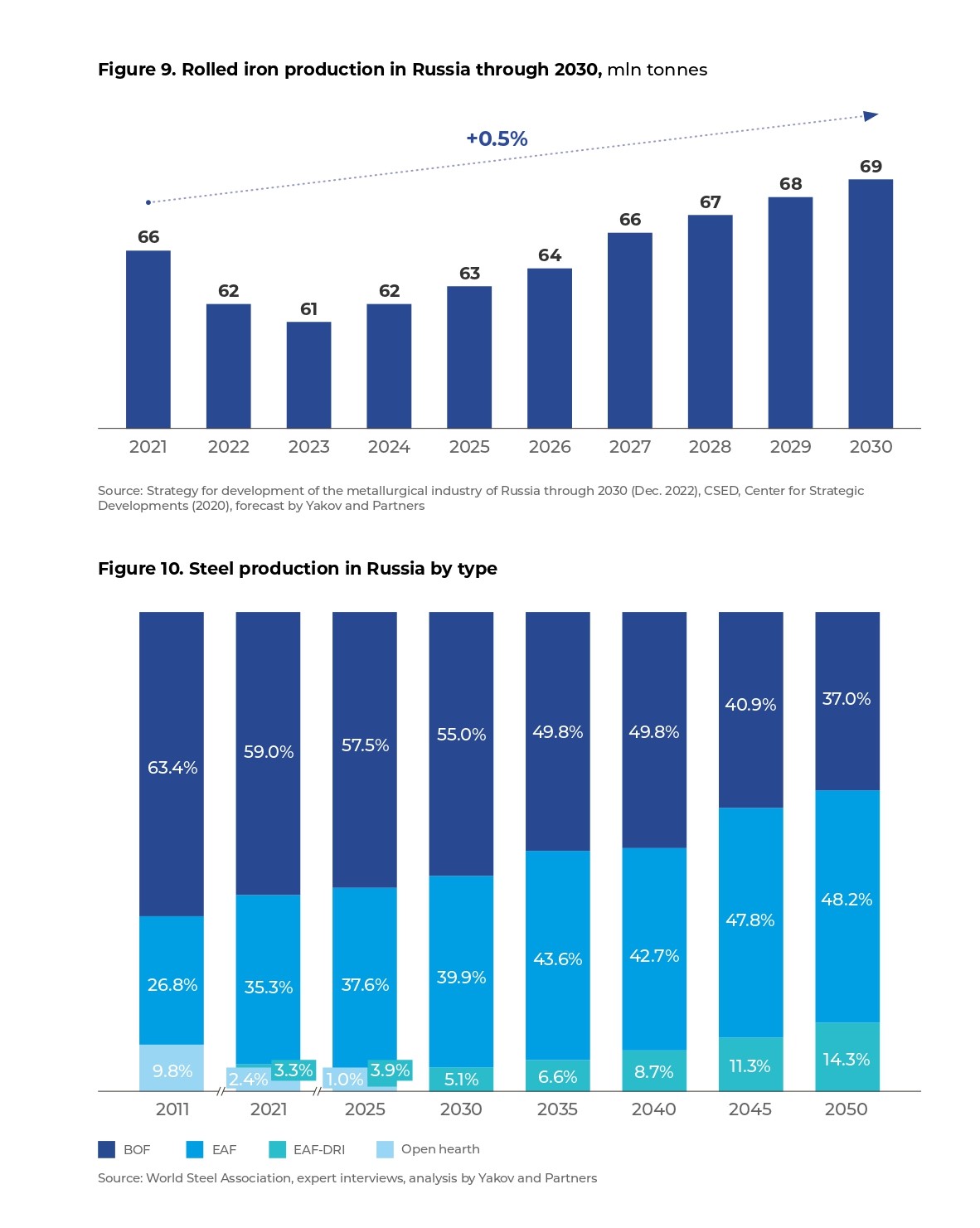

We estimate the domestic consumption of steel (steelmaking drives the demand for metallurgical coal) at about 60 mln tonnes by 2050. In 2022, the key consuming segments (including export) were the construction sector (33%), pipe rolling and power industry (13%), machinery manufacturing (12%), and other segments (1%). The share of the construction sector is expected to decline from 33% in 2022 to 29% in 2050 (Figure 6). In our estimation, the export of steel from Russia will decrease from 29 mln tonnes in 2021 to 25–26 mln tonnes in 2022–2023. Nevertheless, we forecast a long-term trend towards growing supplies: Russia will be able to return to the level of 2021 in 2030–2035 by expanding the geography of its supplies to Asia.

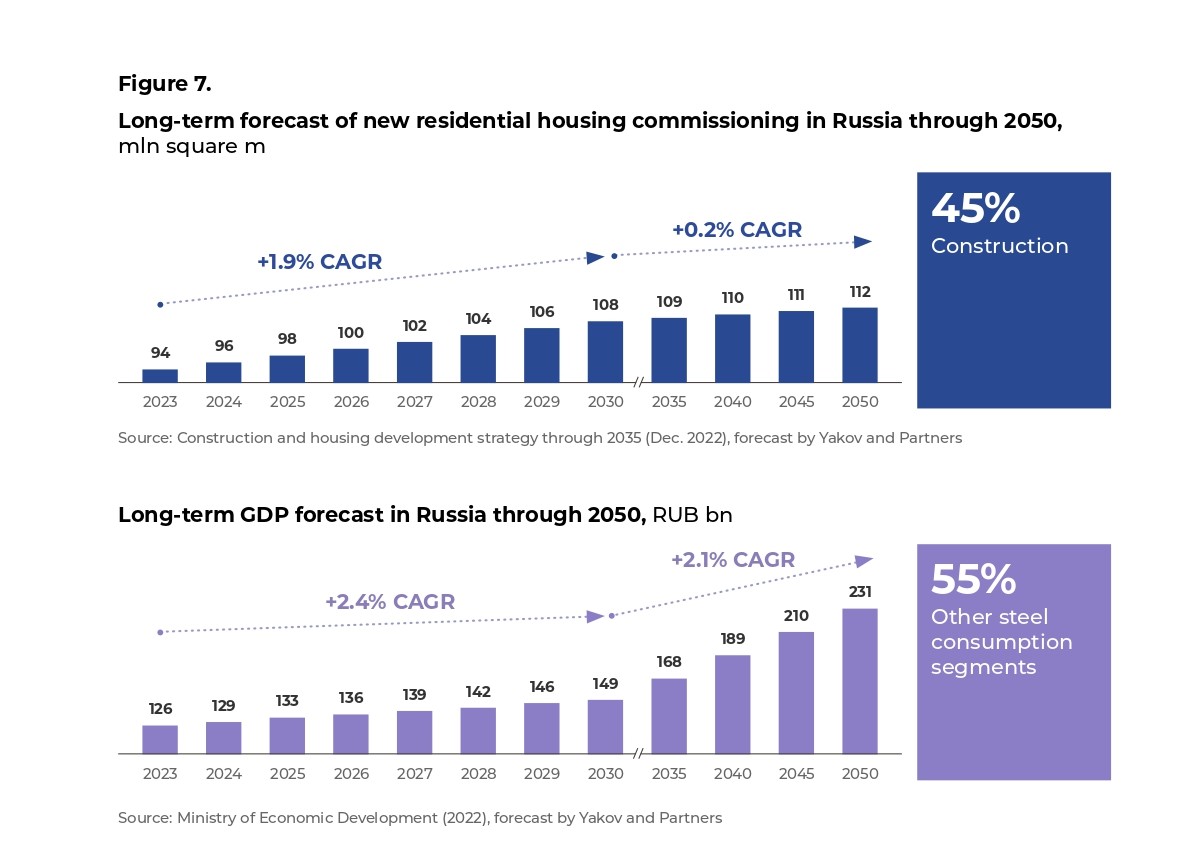

We estimate that steel consumption will grow due to expanding housing construction and general economic growth. In particular, residential construction will grow at a rate of approximately 2% per year through 2030. It is worth noting that, in our estimation, the Ministry of Construction’s plans for annual commissioning of 120 mln square meters of residential space will be realized for only 90% by 2030. The key reason is insufficient demand caused by the long-term decline in population and stagnating income (Figure 7).

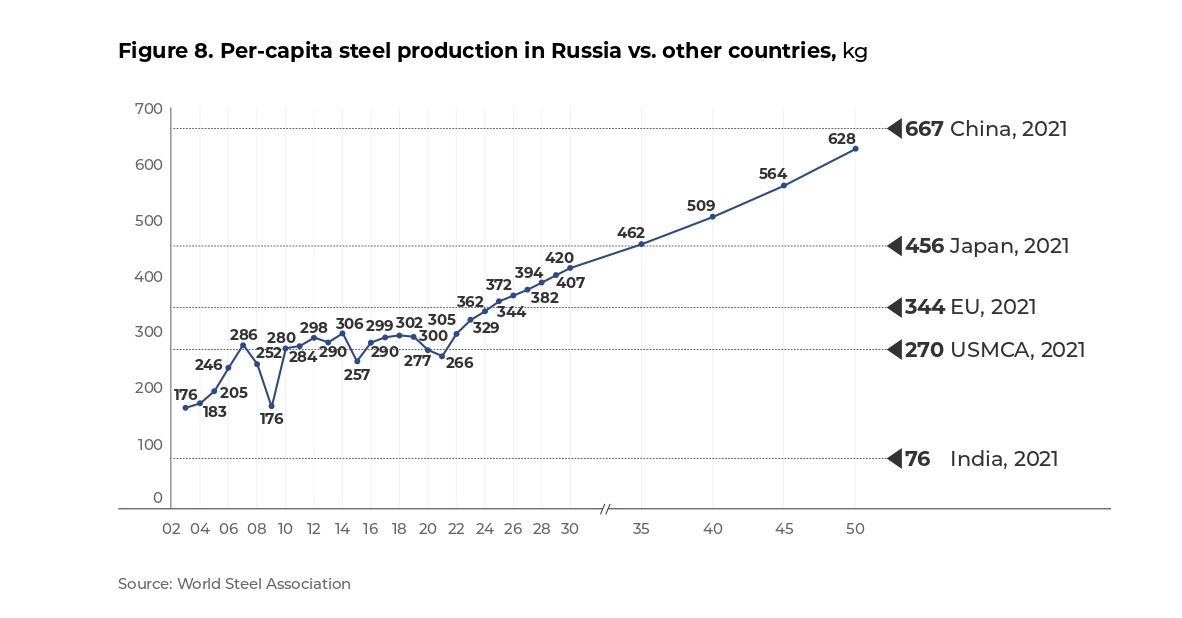

Subject to Russian steel consumption growth of approximately 2% per year and a population decline of 0.3% per year, we expect per-capita steel consumption to reach the current EU’s and China’s levels by 2030 and by 2050, respectively (Figure 8).

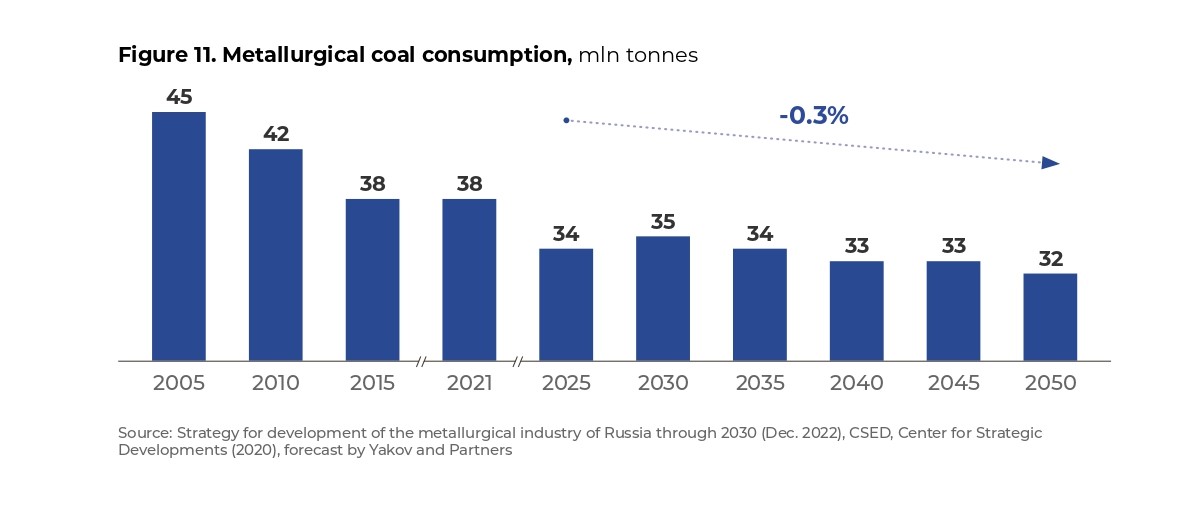

In total, Russia’s consumption of metallurgical coal, in our estimation, will decrease by 5% to 34.3 mln tonnes by 2025. The key causes of the negative trend are lower smelting in 2022 (-7%) and subsequent slow recovery in steel output. After 2025, however, metallurgical coal consumption will start decreasing by 0.3% per year (Figure 11).

The reason is that, by 2050, the share of the basic oxygen furnace (BOF) smelting process, which is prevalent in Russia and uses coal (deemed a “dirty” fuel), will decline from the current 59% to 37%. On the contrary, the share of electric arc furnace (EAF) production will grow on the back of the expected introduction of environmental restrictions on a horizon of 2035. In addition to that, the steel industry is ever wider using the DRI process (EAF based on direct-reduced iron), which is key to production of “green” steel with low CO2 emission. By 2050, we forecast that the share of such steel may go up to 15% (Figure 10).

A positive fact for coal miners is that Russia has no official government plans regarding the “green” agenda in the metals industry so far. Nevertheless, six companies that, taken together, produce more than 80% of steel in the country (Severstal, NLMK, MMK, Mechel, EVRAZ, and Metalloinvest) have already set targets for themselves to reduce their CO2 emissions. According to the Russian Coal Industry Development Program 2035, there are plans to expand capacity and coal production by reequipping production facilities, increasing coal washing, and implementing infrastructure projects. In that case, the colliery capacity will enable annual production of 345–518 mln tonnes of thermal coal and 140–150 mln tonnes of metallurgical coal by 2035.

Future of coal in Russia

The most realistic one of our three scenarios for Russian coal market development is the base case. It presumes cessation of coal trade with the EU since 2023, with Japan and South Korea since 2026, and lifting of Chinese restrictions on coal supplies from Australia as early as this year. The base case also includes retention of current GDP growth rates in the developing economies, stagnation or zero growth in the developed ones, and moderate energy prices.

If this scenario is realized, the share of coal in Russia’s energy balance will remain at 10.4% through 2030 and decrease to 10% by 2050. At the same time, the share of renewables will triple to about 3% by 2035. The metals industry will also see a limited transition to EAF processes, including with DRI, and a reduction of BOF share to 38% while the influence of new technologies, such as, for instance, unmanned equipment in coal production, will affect only 1% of all collieries. The annual average growth rate in per-capita power consumption will amount to 0.6% in Russia through 2050.

The Accelerated Transition scenario presumes quick lifting of trade restrictions, return to the previous growth rates in the world economy, continuing “green” agenda with a relatively fast transition to “green” technologies, and high energy prices. In that case, the share of coal in Russia’s energy balance will drop at a faster pace (to 10% in 2030 and to 8.5% in 2050) while the share of renewables will grow to 6–7% by 2050. The country will also see an accelerated transition to EAF and DRI steelmaking while the share of the BOF process will go down to 34% by the target year. Production cost cutting technologies will be implemented at 10% of all collieries. Per-capita power consumption will grow in the country at a higher pace (1.1% per year).

The third scenario, Recession, provides for a global crisis with a deeper split of the world economy into two economic “clusters”. The developing economies (Russia, China, India) and the developed ones (EU, USA, Japan, South Korea, Australia) will trade exclusively among themselves. In that case, the world economy will face stagnation until 2026–2027 and depressive stunted growth in the next 5–6 years. Due to the recession in this scenario, the developing economies will mostly look at purely economic parameters when making decisions on how to provide their economies with the required power while the implementation of the “green” agenda targets will bog down. If the scenario is realized, the share of coal in Russia’s energy balance will stay at 10.9% through 2050 while the share of renewables will never go above 1.5%. Russia’s power consumption will grow by 1.1% each year. The development and implementation of disruptive technologies in coal mining will be frozen until 2035, and the BOF process, which is currently prevalent in the metals industry, will decrease to 45% by 2050.

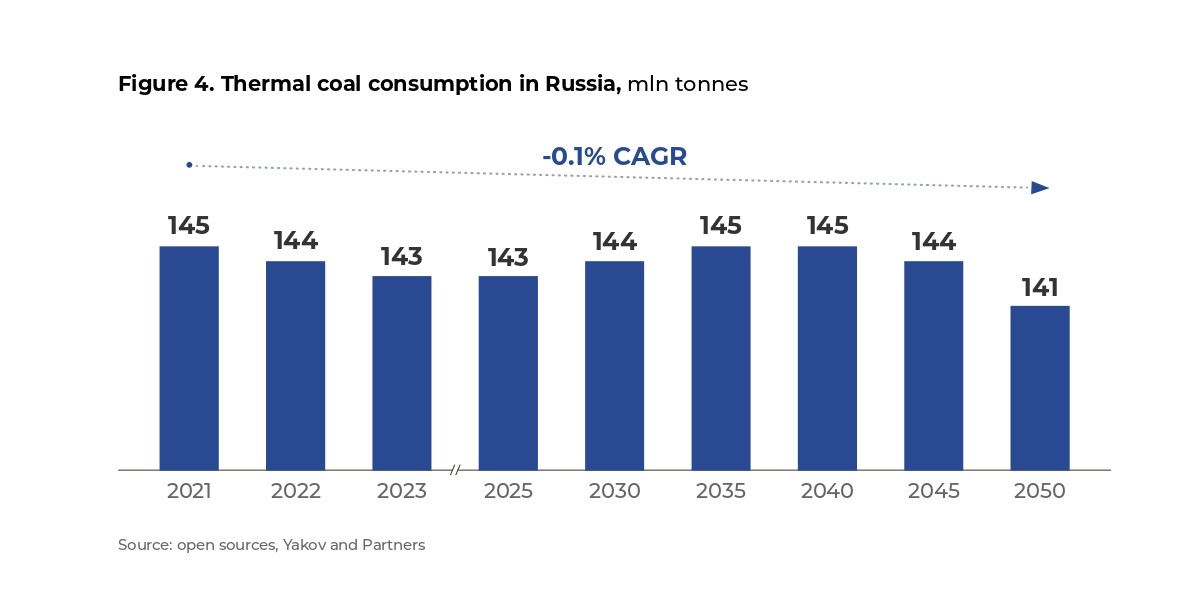

Under any of the three scenarios, coal will remain an important component of Russia’s energy balance in the next three decades. Both the gasification program and a higher share of renewables will somewhat reduce thermal coal consumption but the economic efficiency will support continuing demand for thermal coal from power generation through 2050 at a rate of at least 92% of the current level (and at least 96% until 2035). The risks of collapsing demand for coal, which concerned several industry leaders in the past 3–5 years, did not realize and will hardly realize in the future. The demand in general will still stagnate, however, and will start declining, albeit in the longer term. The environmental agenda will also remain although its focus may transform due to “disengagement” from the targets, which are set mostly by western countries, and shift from CO2 towards elimination of polluting emissions.

In this setting, it is worthwhile for industry players to use the emerging pause to focus on making their production more efficient and environment-friendly, including by building a digital infrastructure and electrifying their equipment, and on seeking export sales destinations for the metallurgical coal fields they have in operation or under development.

Another potential long-term line of work for collieries is the development of their consumer relations in order to reduce the adverse environmental impact of coal combustion. Among such initiatives, we can mention financing of the development and implementation of methane capture and disposal technologies, technologies for improving power plant efficiency from the current 35% to 40–50%, and investing in coal gasification projects.

Taken together, those efforts will enable coal producers to keep the returns on their assets and provide a long-term contribution to the development of the power industry and economy and conservation of the natural environment.

Conclusion

To analyze the situation in the coal industry, we have built three development scenarios: Base Case, Accelerated Transition and Recession.