Export remains a priority for the Russian coal industry. In 2022, more than half of the national coal output was shipped abroad. Following last year’s sanctions imposed by the European Union (EU), Russian coal producers were forced to seek alternative markets to substitute for the larger and more profitable European market. The Ministry of Energy estimates that amidst the global logistics disruptions, Russia lost about 1% of its exports, as total supplies to the global market exceeded 221 mln tonnes of coal in 2022¹. Whether these results can be sustained will depend on Russia’s ability to increase its share of Asian markets and find new consumers.

Our third and final overview of the coal industry looks at Russia’s export potential through 2050, taking into account the key challenges and possible growth points. As with our previous reports, we considered three scenarios when analyzing the development trends in the global coal market: Base case, Accelerated development, and Recession. Based on our estimates, the Base case scenario is deemed the most probable.Key consumers of the Russian coal

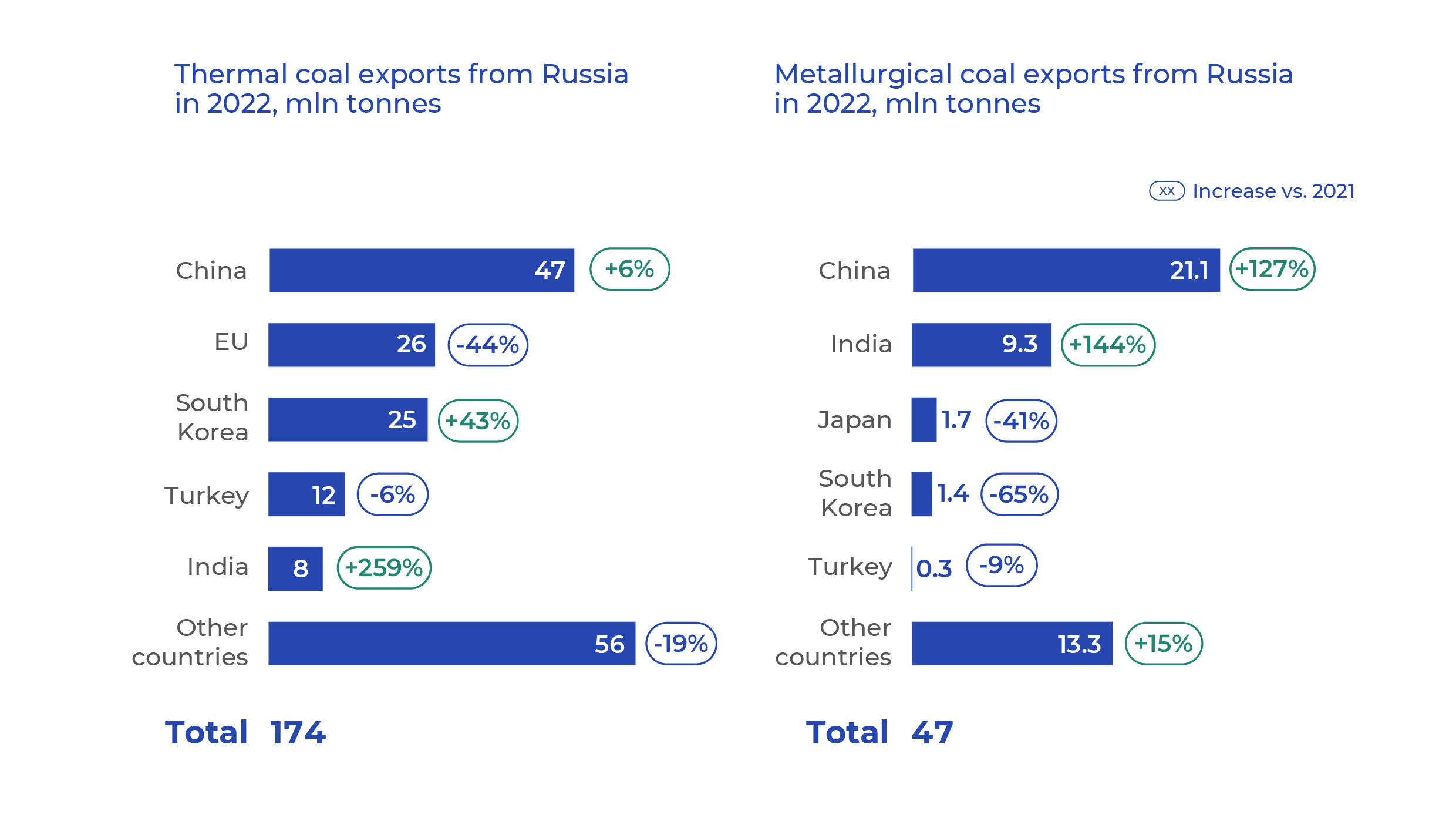

In 2022, China remained Russia’s main export market with 47 mln tonnes of thermal coal (27% of total exports) and 21 mln tonnes of metallurgical coal (45%).The geography of other export flows changed dramatically in response to the deterioration of the geopolitical situation and imposed sanctions. Direct supplies of Russian coal to a number of key traditional importers, in particular the EU and Japan, were curtailed or stopped altogether. By contrast, India came to the fore, becoming the second largest importer of metallurgical coal after China (20% of exports) and a top-five importer of thermal coal (5% of exports). Turkey and South Korea remain among the key buyers of both types of coal, but the latter is likely to slash its imports of Russian coal by the end of 2023.

Key importing countries

According to our estimates, by 2050 most of Russia’s coal export flows will be south-bound, going to South-East Asia and the Middle East. India and China will gradually cease to play a key role for Russian thermal coal exports in the period under consideration due to their long-term ambitions to reduce consumption (China) and become self-sufficient (India).

The most promising destinations for Russia’s metallurgical coal supplies by 2050 will be South-East Asia and India. Below is an overview of key coal-consuming countries.

China

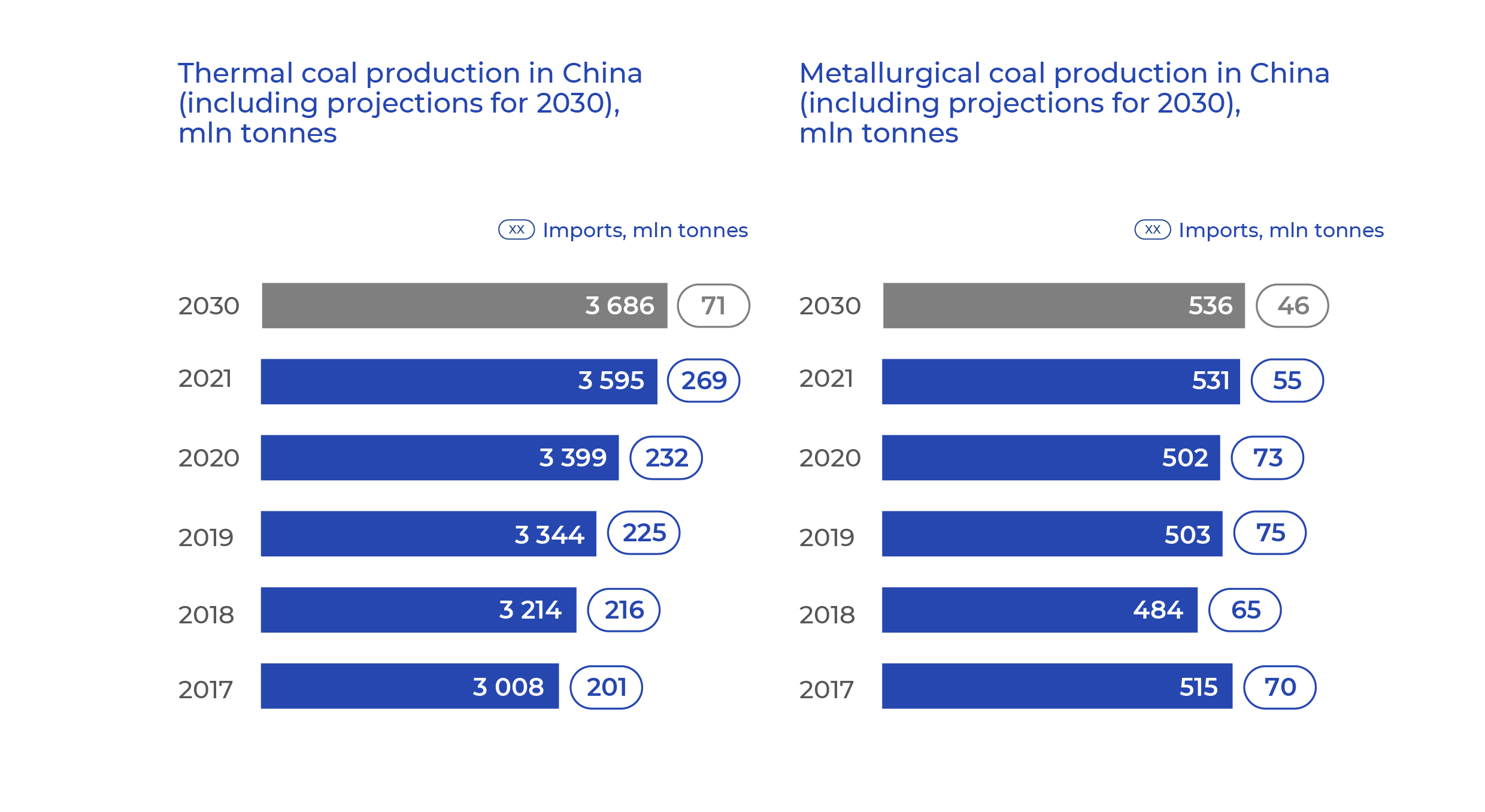

The volume of coal imports to China will keep declining through 2030. Production growth in the country has historically been driven by the ever-increasing energy consumption and the significant share of coal in the power generation mix. Given China’s goal to reduce the share of coal in the energy mix, consumption is expected to gradually decline after peaking in the mid-2020s.

At the same time, domestic coal production already meets more than 90% of China’s thermal coal consumption needs, and new coal projects scheduled for commissioning before 2030 could provide an additional 65 mln tonnes of coal annually.

If the annual consumption remains at the 2021 levels, we estimate that China’s proven coal reserves (208 bn tonnes) will last it for about 47 years. Given the government’s ambitions to become self-sufficient, by 2030 China’s thermal coal imports may fall below 100 mln tonnes per year, with the bulk coming fr om the neighboring Mongolia and Indonesia supplying cheaper fuel.

China has the potential to meet domestic demand for metallurgical coal using its own production capacities; yet the short-term increase in production will be limited as new projects will add just about 5 mln tonnes by 2030. At the current production level, active deposits of metallurgical coal (39 bn tonnes of proven reserves) should be sufficient for about 70 years. We estimate that imports of metallurgical coal to China will decrease by 15% by 2030, to 46 mln tonnes.

India

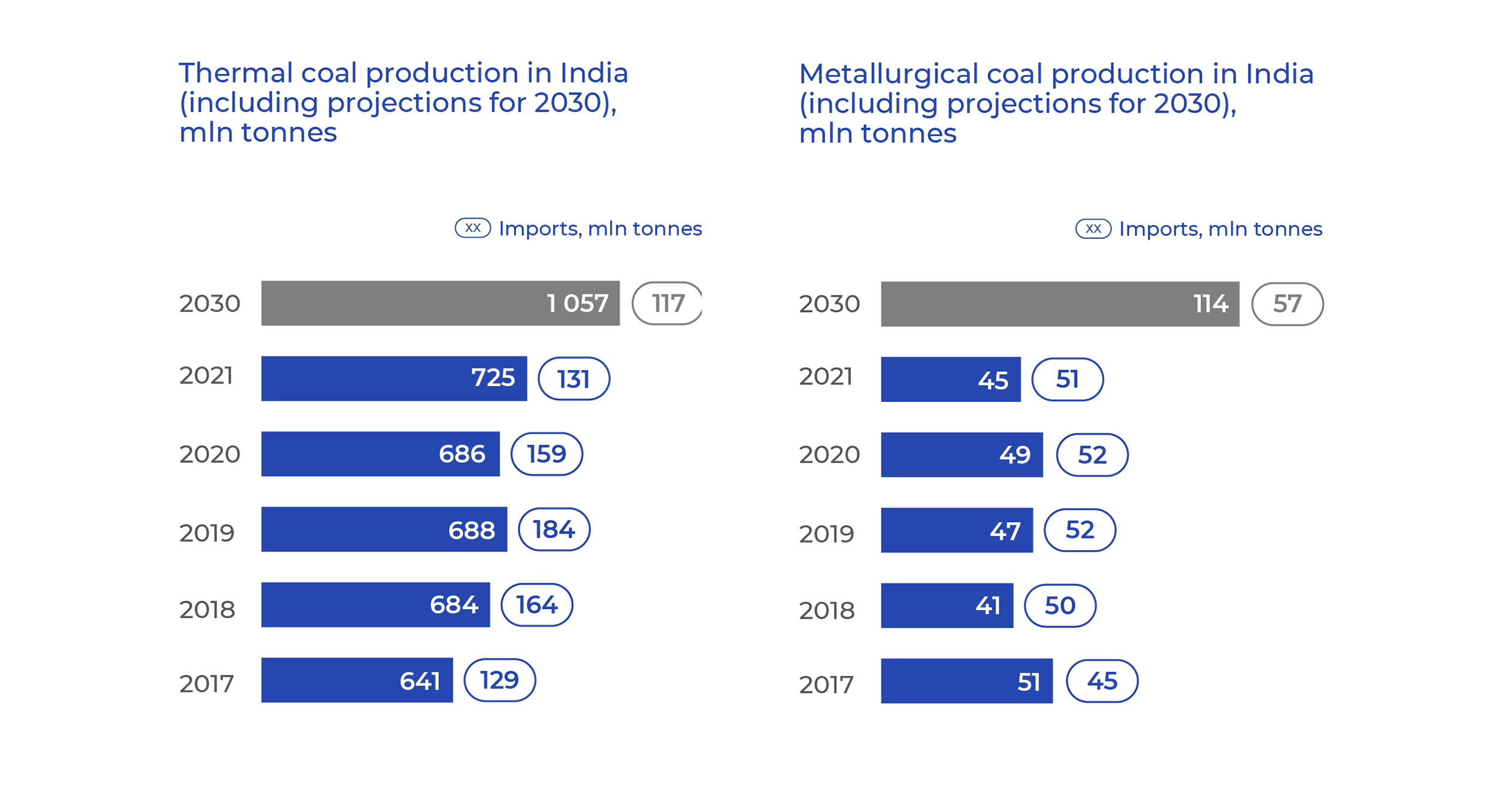

India also has long-term plans to reduce its dependence on imports of thermal coal. The Indian government considers coal one of the most attractive sources of energy due to its availability and the relatively low cost of generation.

By 2030 production volumes are expected to increase almost by 50% vs. 2021 and exceed 1 bn tonnes. As a result, imports may decline by over 10%, to 117 mln tonnes.

On paper, new projects could boost annual production by 635 mln tonnes, which would potentially cover almost 90% of domestic demand. At the level of consumption expected by 2030, we estimate that India’s coal reserves (about 368 bn tonnes) will be sufficient for more than 300 years.

Although India’s imports of metallurgical coal currently exceed domestic production, with its 53 bn tonnes of reserves, India could ramp it up by approximately a factor of 2.5 (to 114 mln tonnes) by 2030. New projects scheduled for that period could provide an additional 69 mln tonnes of coal per year. The cost of production will range from USD 20 to 30 per tonne, which is lower than in other countries. Imports of metallurgical coal may grow by more than 10% by 2030, to 57 mln tonnes.

The European Union

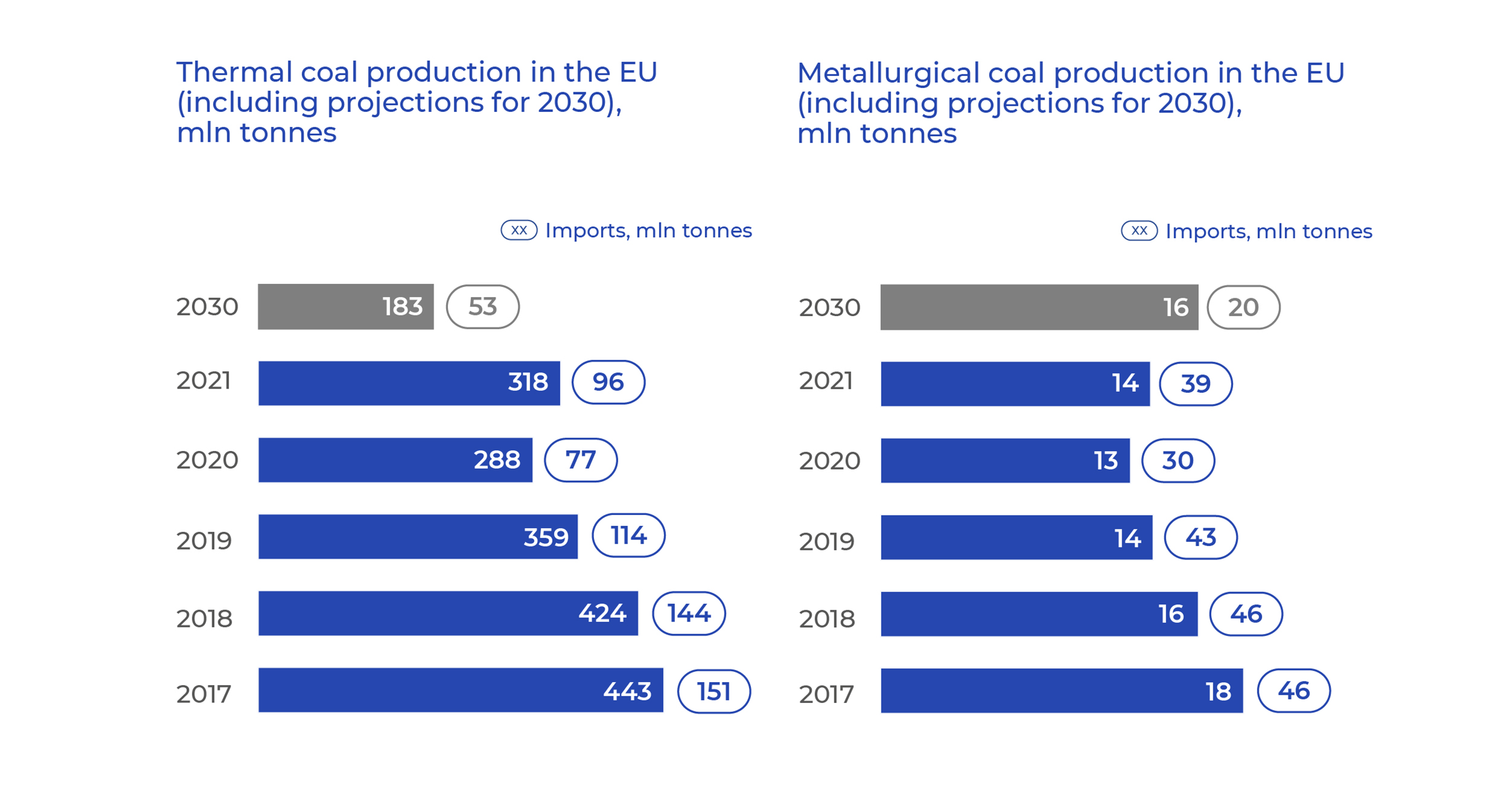

The EU will reduce thermal coal production by 2030 due to a more than 40% decline in demand for this fuel. The EU has no new coal mining projects in the works due to the green agenda, the EU Green Deal, and high carbon prices (around USD 30 per tonne). At the same time restarting most mothballed coal mining assets (mainly mines) would be more expensive than commissioning new renewable energy projects.

Despite the loss of huge volumes of imported thermal coal from Russia, we expect production in the EU to resume its downward trend and decline to 183 mln tonnes by 2030 vs. 318 mln tonnes in 2021 (-43%). We estimate that by 2030 EU imports of thermal coal will decline by 45%, to 53 mln tonnes.

As there are no new large metallurgical coal projects in the works either, production is expected to grow to only 16 mln tonnes. Most mines in the region are at least 30 years old, and their output is steadily declining. Besides, coal mining in the EU is unprofitable due to limited government support and expensive labor. The main producer of metallurgical coal in the region is Poland, wh ere a new asset producing an annual 2.2 mln tonnes is planned to reach full capacity by 2025.

Key exporting countries

Indonesia will steadily increase thermal coal production through 2030 to meet the growing demand in the domestic and export markets. Coal exports from Indonesia will grow by 10% by 2030, to 474 mln tonnes. Its confirmed coal reserves (45 bn tonnes) will be sufficient for about 55 years.

Although Indonesia is not a major exporter of metallurgical coal, according to our forecasts, its production and exports will be rapidly growing. By 2030, production will increase fivefold, to 22 mln tonnes, and exports will more than quadruple to reach 8 mln tonnes.South Africa is expected to restore thermal coal production to 240 mln tonnes by 2030 after a decline in 2020–2021, yet production is not expected to exceed the 2020 figures (245 mln tonnes).

The share of exports, according to our estimates, will remain approximately the same at around 30%. By 2030, exports from the country will decrease by 4.5%, down to 63 mln tonnes. No significant changes in the export flow structure are expected.

South Africa is not a major exporter of metallurgical coal and we do not expect it to ramp up exports in the foreseeable future.

Australia’s coal production will remain at around the 2021 levels. Currently, about 67% of all the thermal coal produced in the country is exported. By 2030, this figure will rise to 75%, while exports will increase by 12% to reach 223 mln tonnes in absolute terms.

More than 90% of metallurgical coal produced in Australia is also exported. We do not expect production to grow actively in the future and estimate that by 2030 it will increase by a mere 6%, to 181 mln tonnes. In turn, metallurgical coal exports will increase by 5% to reach 176 mln tonnes.

Logistics issues

Ocean freight rates for coal are currently relatively low, but are expected to rise in the future. By 2028 logistics costs may increase by 20% triggered by the decarbonization of shipping. Afterwards, freight rates will stabilize due to the falling global demand for coal. The lowest cost of freight to China would be from Russia and Indonesia, and to India – from Indonesia.

Projected cargo flows of Russian coal through the Northern Sea Route (NSR), according to our estimates, will amount to 5–7 mln tonnes per year by 2026 and will further increase to 10–12 mln tonnes. River routes via the NSR are not a viable alternative for coal transportation due to their unprofitability.

Prospects of Russian coal exports

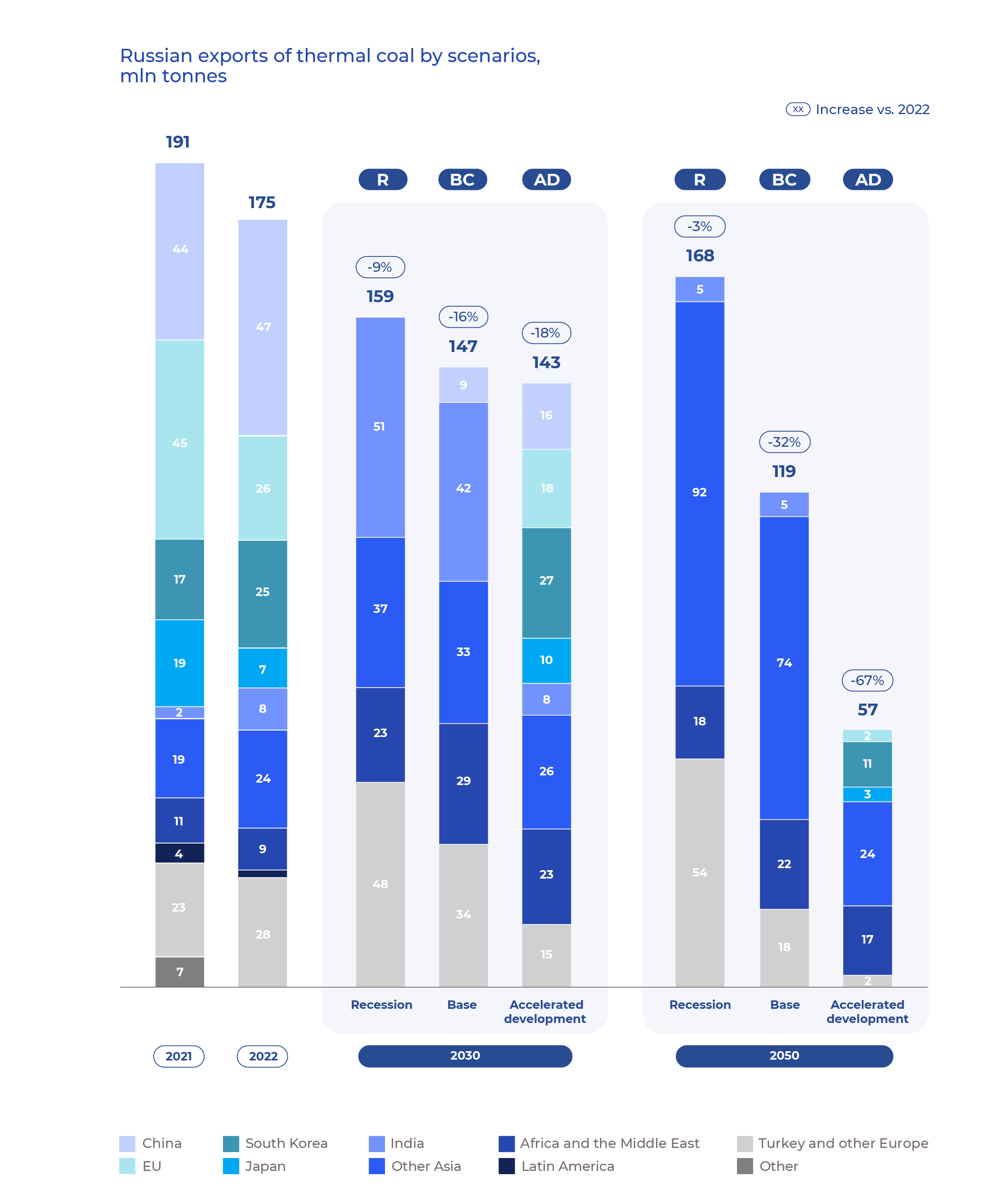

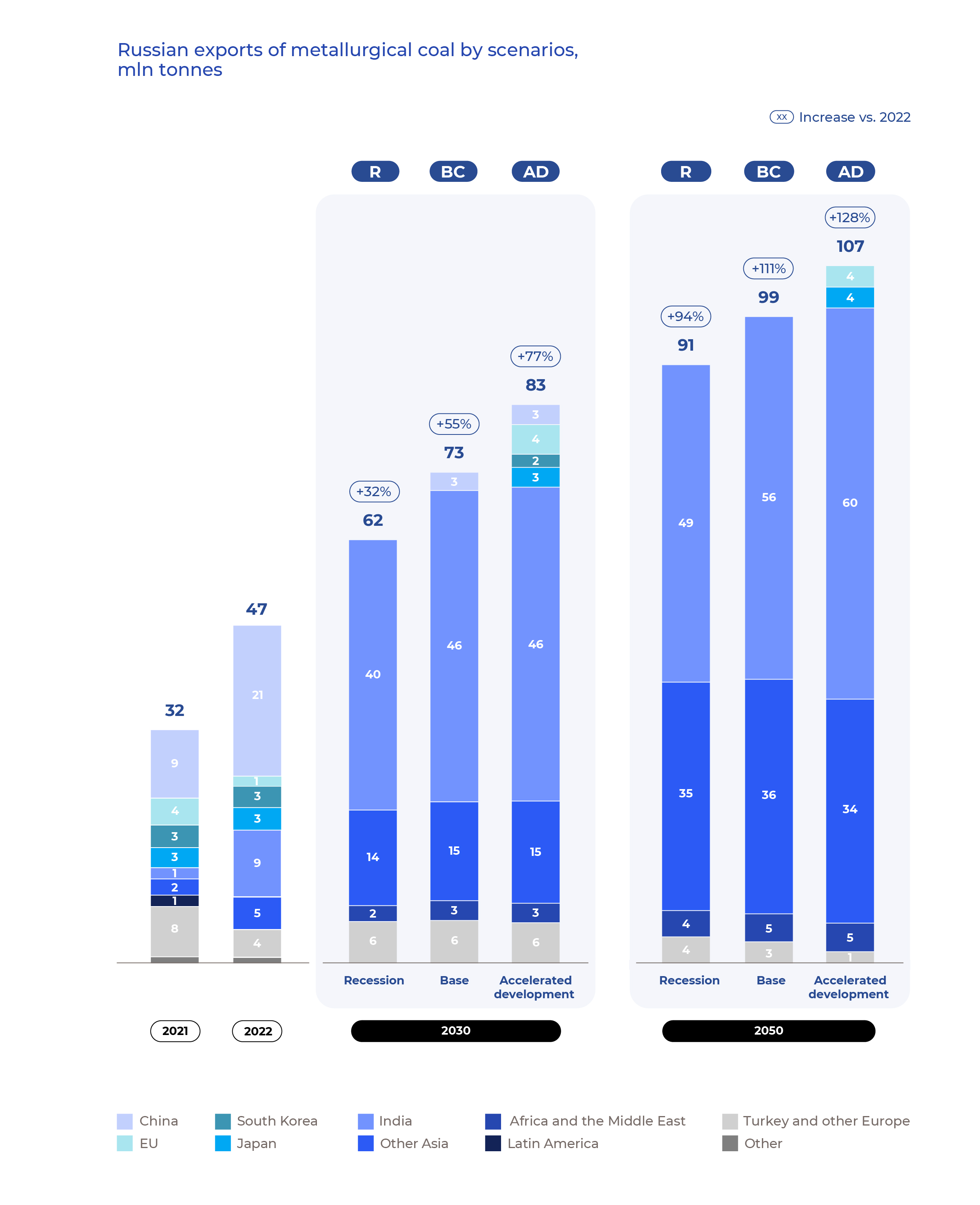

As we indicated in our previous reports, we considered three scenarios when analyzing the development trends in the global coal market: Base case, Accelerated development, and Recession. All the three scenarios envisage a decline in thermal coal exports from Russia and a rise in metallurgical coal exports.

The global export market for thermal coal in the Base case scenario will shrink due to a declining share of imported coal in China’s and India’s consumption. Russian exports of thermal coal will not rebound to the 2021–2022 levels even until 2050. Taking into account the foreign trade restrictions, Russian suppliers should focus on alternative markets. In 2023–2025, export volumes are expected to fluctuate as some of the export flows will be redirected from a number of “unfriendly” countries (e.g., Japan, South Korea).

As the key consumers of Russian coal become increasingly self-sufficient, supplies are expected to drop to 5–10 mln tonnes per year by the mid-2030s in case of China and by 2050 in case of India. At the same time, by the early 2030s exports to South-East Asia will be on an upward trend, but Russian suppliers will have to significantly reduce their production costs to compete with Indonesian coal producers.

With regard to the most mutually beneficial distribution of coal between exporters and buyers, by 2030 the key consumers of Russian thermal coal will be India (about 30%), Turkey and non-EU European countries (20–25%), and South-Eastern countries (20–25%). By 2050, more than 60% of Russian thermal coal will go to other Asian countries (this category includes Asian economies with the exception of China, India, Japan, South Korea, the Middle East, and Turkey, i. e. mainly South-Eastern countries).

Russia also has the potential to become a major exporter of metallurgical coal to India and Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Taiwan due to the active growth of demand for this fuel in the region. Middle Eastern countries (Iran, Lebanon, and the UAE) and non-EU European countries (mainly Turkey) will also keep importing Russian coal. China will gradually reduce its imports of Russian metallurgical coal in an effort to become self-sufficient.

As to the most mutually beneficial distribution of metallurgical coal between exporters and importers, by 2030 more than 60% of Russian exports will go to India, about 20% of exports will be directed to SEA countries, and less than 10% will go to Turkey and non-EU European countries. By 2050, India’s share will drop to 55%, while the share of other Asian countries will grow to 30–40%, with another 5% of exports going to the Middle East.

Conclusion

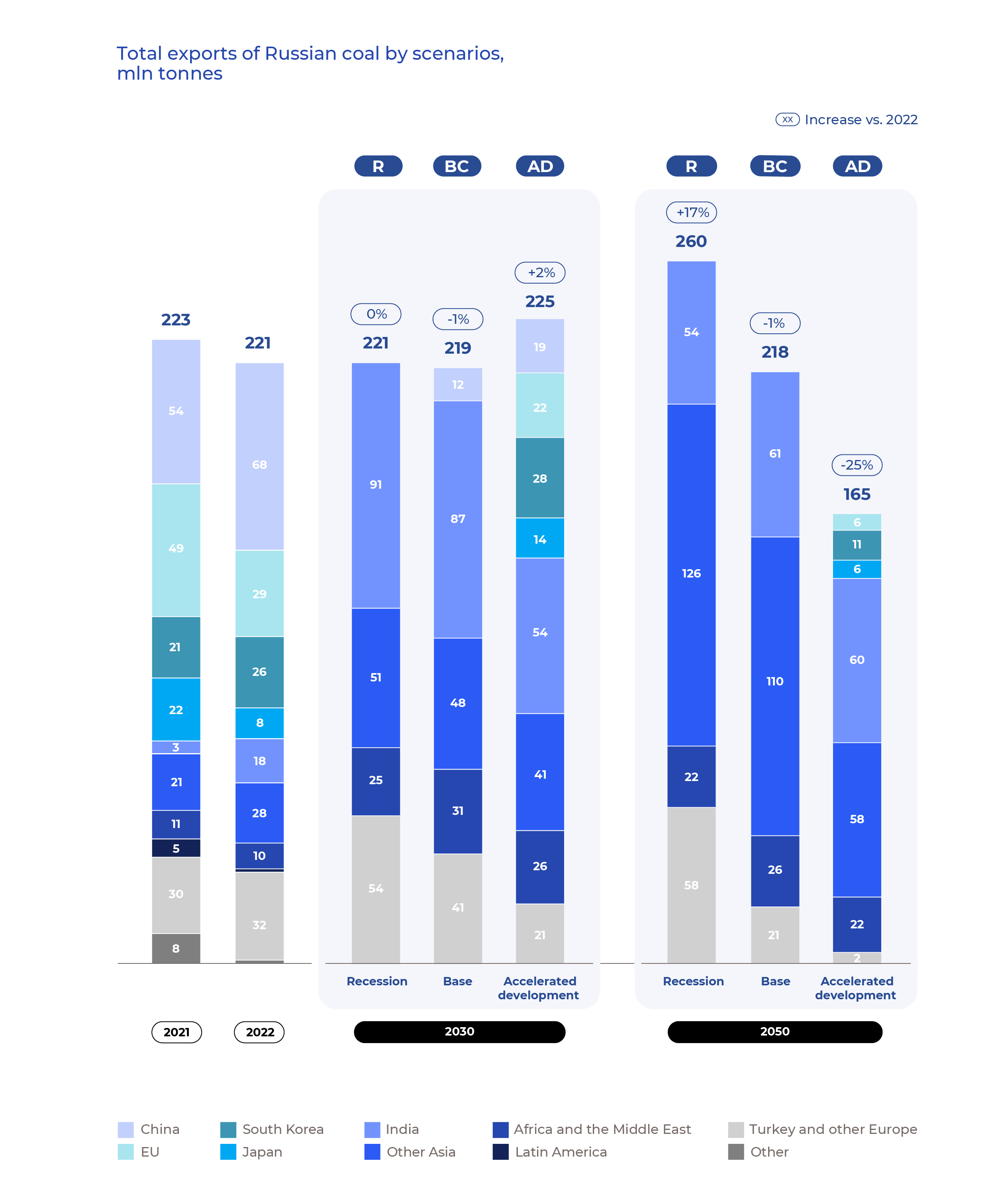

In the Base case scenario, total exports of thermal and metallurgical coal from Russia will not be strongly affected. According to the Ministry of Energy, in 2022 exports totaled at about 221 mln tonnes. By 2030 they will slightly decrease, to 219 mln tonnes (-1%), and by 2050 they will amount to 218 mln tonnes. Thus, the decline in the exports of thermal coal will be offset by a rise in the exports of metallurgical coal.

In the other scenarios, there is a great deal of variation. In the Recession scenario, exports will remain stable until 2030, but will grow to 260 mln tonnes by 2050 (+17% vs. 2022). In the Accelerated development scenario exports are also expected to remain stable through 2030 only to nosedive to 165 mln tonnes by 2050 (-20–25%).

In the Base case scenario, the main buyers of Russian coal in 2030 will be India (about 40%), other Asian countries (20–25%), Turkey and non-EU European countries (about 20%). African and Middle Eastern countries will account for about 15% of exports, while China will account for about as little as 5%.

By 2050 the structure of the main export destinations will change. The share of other Asian countries will grow to about 50%, while India’s share will drop to 25–30%. Africa and the Middle East will take up 10–15% of Russian coal exports, while non-EU European countries (including Turkey) will account for about 10%.

Given the change in the key export destinations, Russian suppliers will have to diversify and further develop a variety of new trade relations. To remain competitive in a highly uncertain environment, exporters will need to have all the tools allowing to quickly switch between the markets. Industry players need to revisit or even completely revise their product strategies and pricing policies, as well as identify new distribution opportunities focusing on foreign counterparties with whom they have previously had only limited interaction.

The Asia-Pacific region will become the target export destination, while India will become the focus market for metallurgical coal. Expansion to the southeast will depend on overcoming two challenges: competitive pressure from Indonesia and Australia, as well as infrastructural constraints within Russia, especially rail access to sea ports.

The long-term future of Russian coal producers (after the stabilization of prices in the global energy market) largely depends on the response of the transport sector, which needs to act immediately. Transport and logistics companies and coal producers need to work out an optimal cooperation format, whether it is joint infrastructure projects in Russia, joint ventures to set up distribution abroad, or otherwise.

Industry players may require additional support, primarily from the government, as well as foreign investors. The scale of the required effort, its urgency and the number of potentially involved parties require quick and efficient coordination. The success of projects that clearly transcend the boundaries of the coal industry heavily depends on agreements reached at the higher level between Russia and its key partners.