70–80% is the uplift potential for annual exports of the Russian agro-industrial complex in the medium term versus the 2021 level

Open sources, analysis by Yakov and Partners

Introduction. New drivers of growth

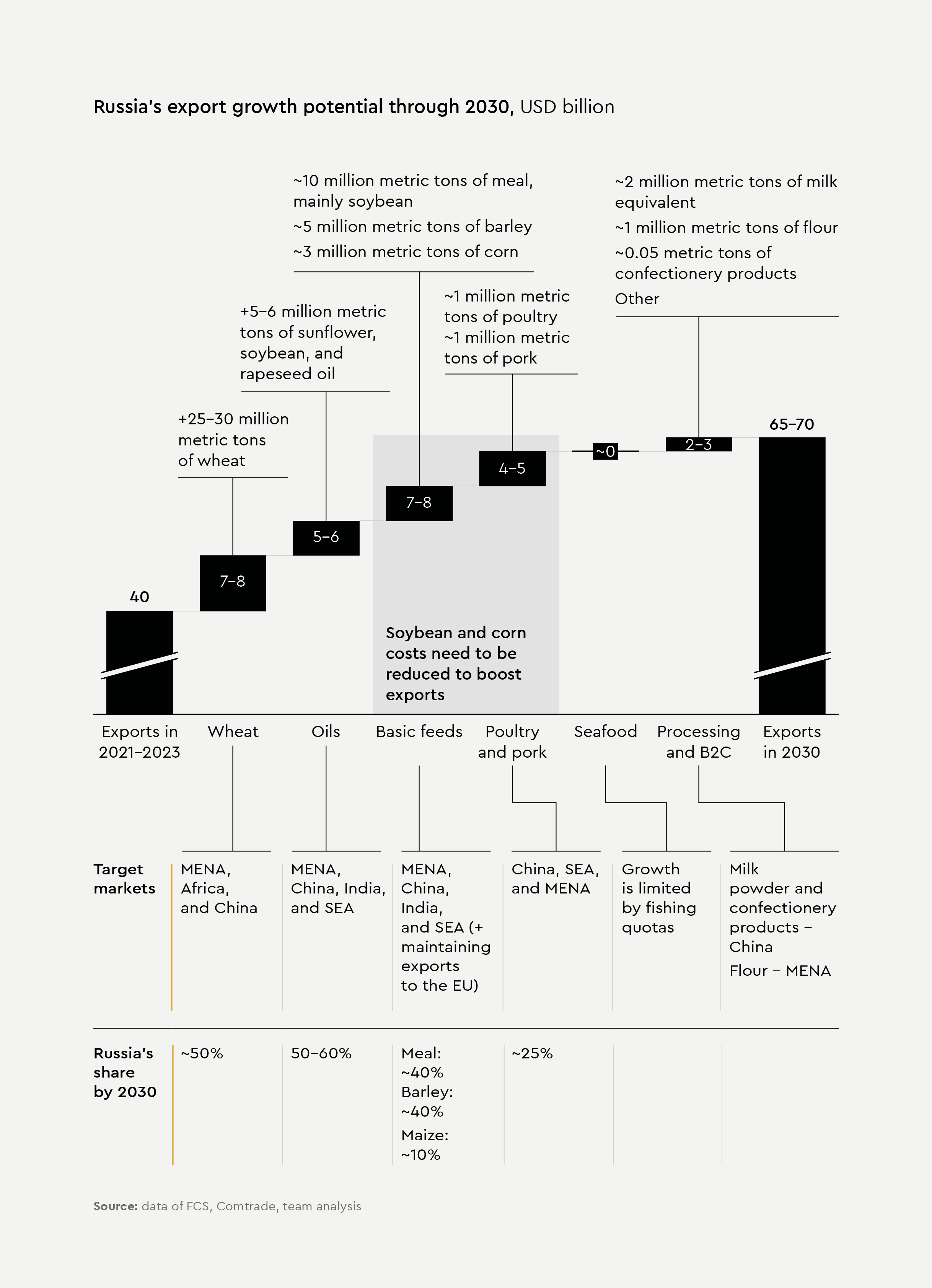

The President has set a new strategic goal for the Russian agro-industrial complex: increasing exports by 1.5 times¹ over the 2021 level, which is equivalent to USD 55 billion per annum. Maintaining the current product structure of exports and the general principles of industry regulation jeopardizes the attainment of this target. At the same time, a consistent focus of both the industry and the regulator on improving the structure of the export product portfolio, achieving optimal structural production costs, and a rational approach to ensuring technological security will make it possible to increase the export potential of the agro-industrial complex to USD 65–70 billion per annum.

Russia’s agro-industry approached the year 2024 with achievements that testify to obvious successes in the development of the industry. Import substitution has long been the main driver of growth in the national agro-industrial complex – as a result, in the first half of the 2020s, food security targets were met for almost all major commodity groups. In 2020–2021, for the first time in modern history, Russia achieved a positive trade balance for agro-industrial products, and in 2023, Russian agro-industrial exports reached a record level of USD 43.5 billion.

Further growth of the Russian agro-industrial complex is possible mainly by increasing supplies to global markets, where Russian agricultural producers face stiff price competition. While domestic production costs for cereals allow for successful competition, Russia lags behind major global suppliers in the production and supply chain for animal proteins

Our new study, based on a comprehensive model of the agriculture sector and the potential of target markets, shows that maintaining the current structure poses risks to achieving the USD 55 billion per annum export target announced in the President's Address to the Federal Assembly on February 29, 2024.

At the same time, a consistent industry and regulatory focus on improving the export product structure and achieving better structural "field to port of destination" costs, combined with a rational approach to technological security, will increase agribusiness export potential to USD 65–70 billion per annum.

For this to happen, fundamental approaches to managing the development of the agro-industrial complex must undergo the following changes:

- Achieve economies of scale by creating "national champions"² with sufficient market power in global markets. Their structure can vary: large agribusinesses (similar to JBS in Brazil), international traders (ADM, Bunge, Cargill, Louis Dreyfus Company) or cooperatives (Copersucar, Coamo, ACA).

- Ensure that national agricultural producers have access to the best technologies to optimize structural costs – efficient genetics³ (including GM crops for feed), advanced inputs (crop protection products, agricultural technologies and equipment).

- Create a sufficient logistics infrastructure for exports and avoid its monopolization.

- Ensure investment attractiveness and profitability of the industry in the context of structural overcapacity.

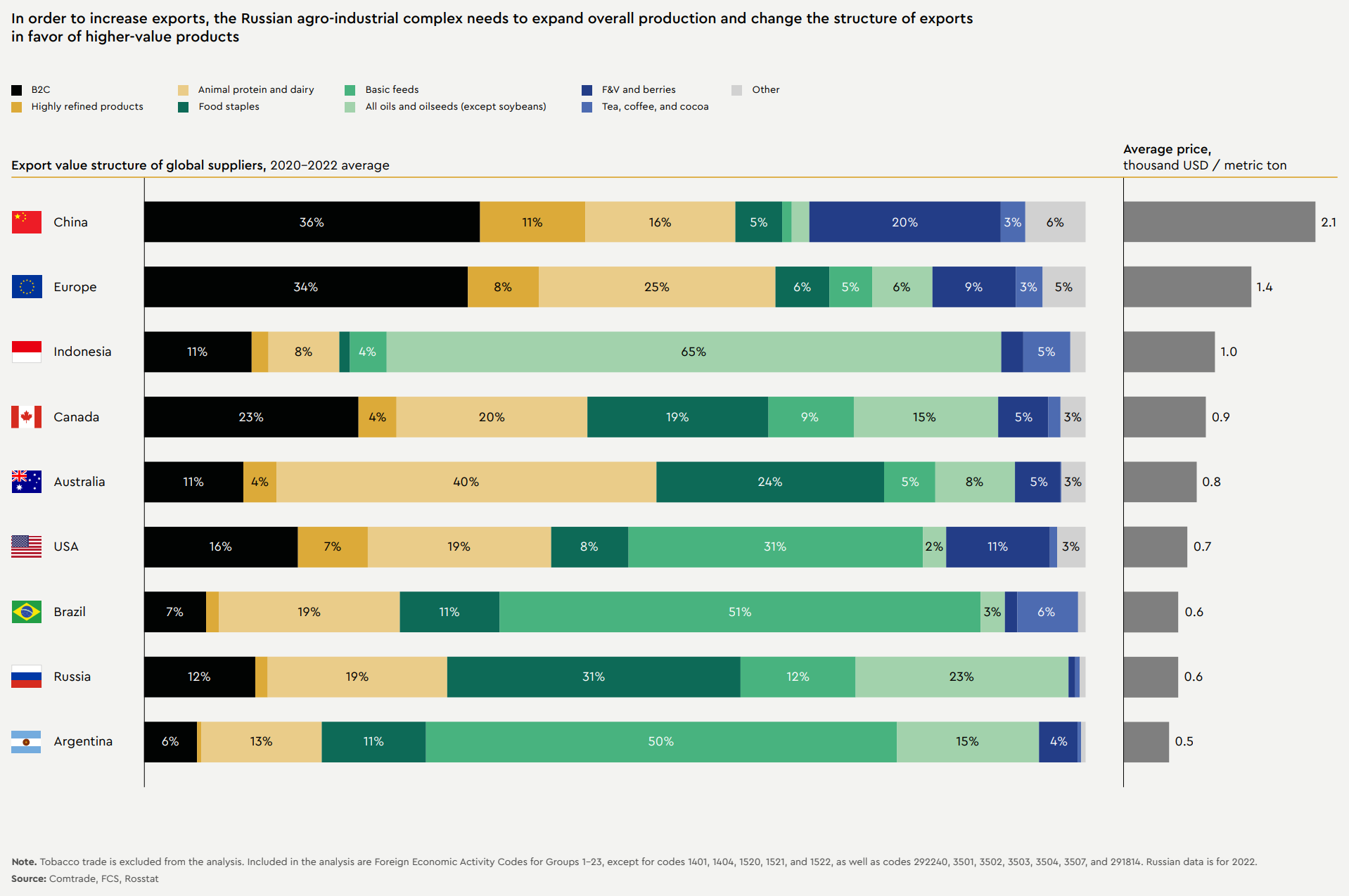

Russia in the global market: exporting a lot, earning little

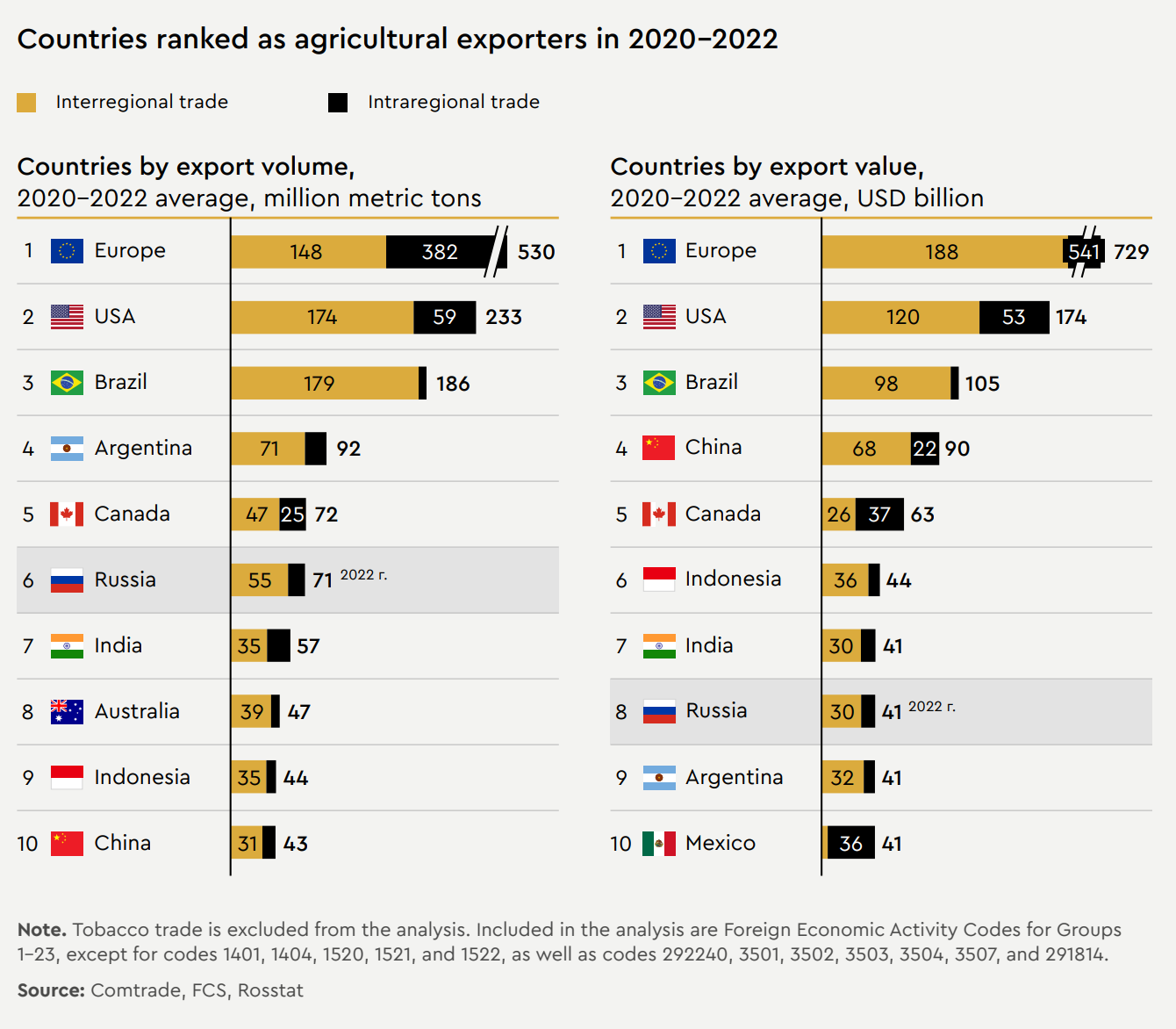

Today, Russia is one of the leading suppliers of agro-industrial products to world markets. In 2023, the country ranked 6th in terms of volume of supply, but only 8th in monetary terms – with a global market share of no more than 2%⁴. This is due to one of the lowest prices per ton of exports among the leaders – around USD 600.

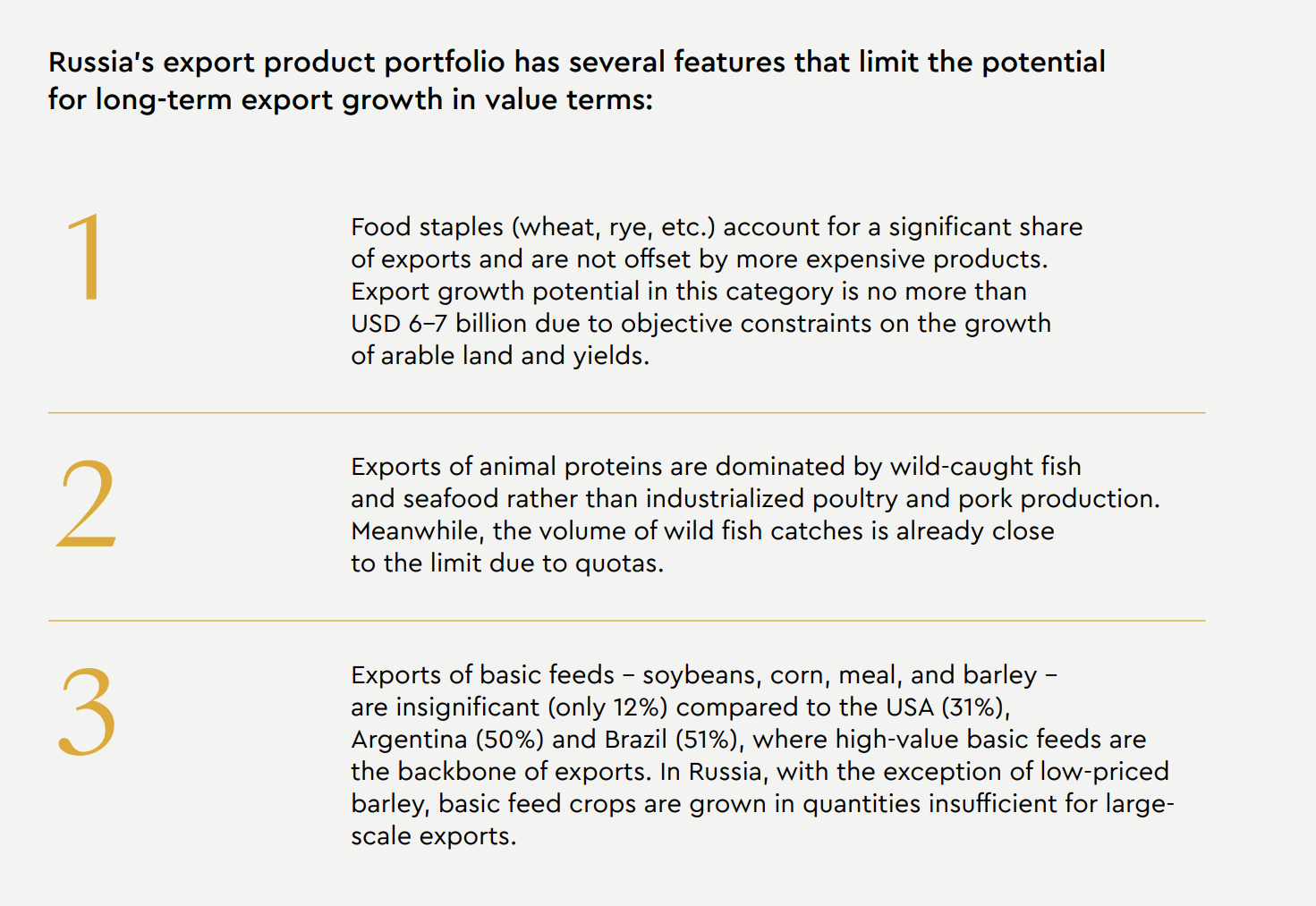

The export structure of global value leaders is dominated by high-value staples and/or downstream products. The leaders in terms of price per metric ton exported are China (USD 2,100) and Europe (USD 1,400), with 40–50% of exports being highly refined and B2C products. Europe has a strong agribusiness sector, but its main export revenue comes fr om alcohol exports under global brands. China has developed a strong food industry, processing local and imported raw materials for domestic consumption and intraregional supply to Southeast Asian countries.

For other global suppliers, highly refined and B2C products account for an average of 15–20% of exports. The higher price per metric ton is due to higher-value commodities: animal proteins, oils or basic feeds, mainly soybean derivatives.

2% is Russia's share in the global agricultural supply market: it ranks 6th in volume and 8th in monetary terms.

Open sources, analysis by Yakov and Partners

Export development: target markets

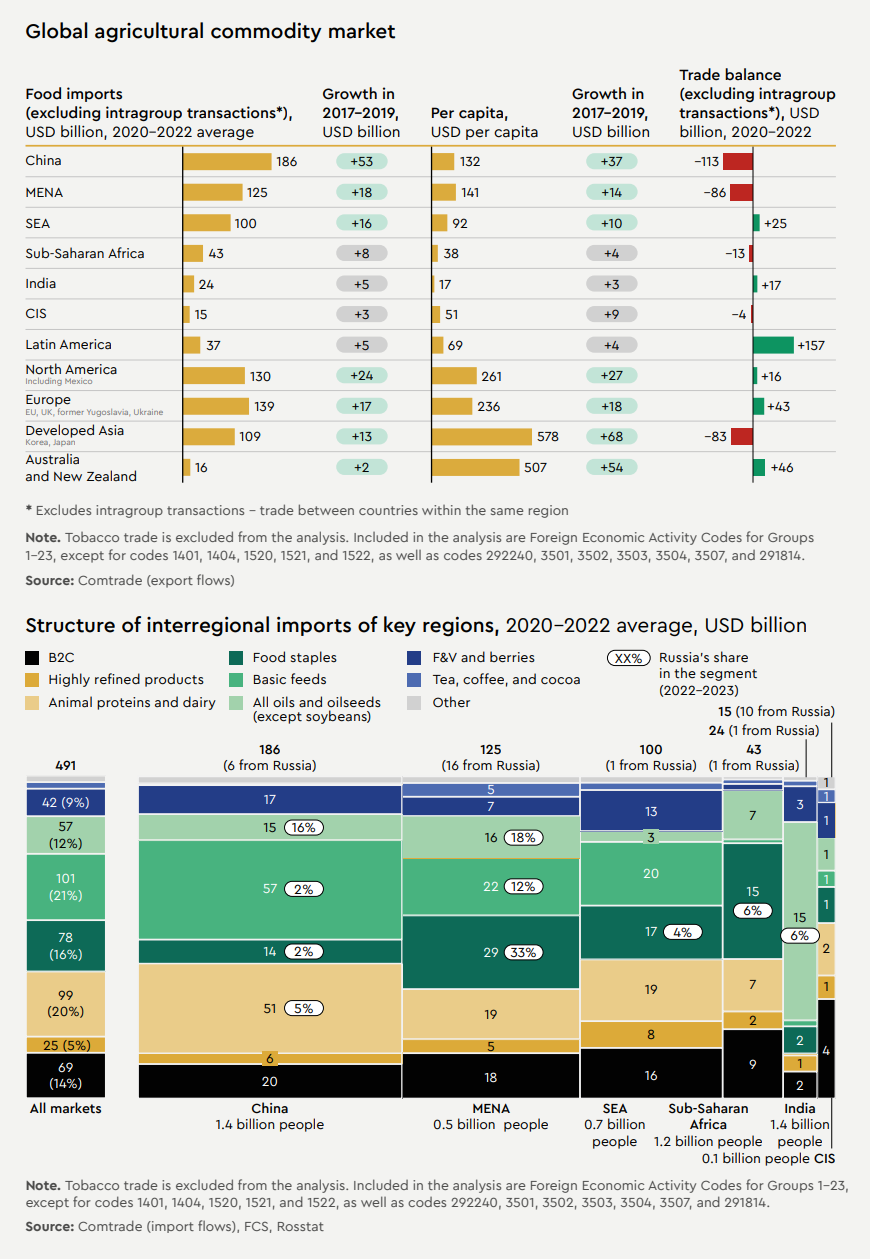

Russia's export potential depends on two factors: the long-term accessibility of global markets for Russian companies and progress in achieving food security goals in different countries and regions. In this analysis, we assume as a long-term base case the fragmentation of the global economic system into large clusters, with a sufficient level of division of labor, logistical connectivity and settlement capacity remaining within the Global South cluster (China, MENA⁵, SEA, Sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Latin America).

The key regions for the development of Russian export will be the markets of China, MENA, SEA, India and, to a lesser extent, Sub-Saharan Africa. For various reasons, the other macro-regions are unlikely to become key drivers of Russian export growth:

- The CIS market is close to saturation with Russian agricultural products, which account for about 70–80% of imports. Further supply growth is possible as a result of population and specific consumption growth, as well as squeezing out competition in certain products, but the CIS market is not large enough to ensure long-term growth of the Russian agro-industrial complex.

- Latin America is the largest supplier of agricultural products to the world market, so exports from Russia are limited to niche products.

- Medium-term export growth to developed markets in North America, Europe, developed Asia, Australia and Oceania is constrained by political factors, well-developed intraregional trade, and affordable imports from Latin America.

China

China is the world's largest food buyer, importing more than USD 186 billion worth of agricultural products annually. Russia accounts for only 3% of China's imports, which is due to the fact that Russia exports very few of the agricultural products that China needs.

- Various basic feeds account for the largest share of China's imports – about 31%, or USD 57 billion. Soybeans from Brazil, the USA, and Argentina total USD 45 billion annually, corn (the USA and Ukraine are leading suppliers) – about USD 5.5 billion, fish and bonemeal (mainly from Peru) – USD 2.4 billion, and barley and meal – about USD 2.1 and 1.2 billion, respectively.

- Animal proteins and dairy products rank second. In the structure of imports, about USD 15 billion is cattle meat (60% from Latin America), USD 9 billion is fish and seafood (mainly from Russia and Vietnam), about USD 9 billion is pork (from Spain, Brazil, and the USA), USD 4 billion is Brazilian and North American poultry, and USD 7 billion is dairy products, of which 50% is milk powder from New Zealand. China can become completely self-sufficient in pork in the medium term, but we believe that limited imports will remain for diversification and security of supply.

- B2C imports account for 11%, or USD 20 billion, of which USD 5 billion is baby food and baby food ingredients, USD 6 billion is alcohol, and USD 2 billion is confectionery and chocolate.

- Imports of vegetable oils total about USD 11 billion, of which 40% is palm oil, while other oils are imported from Russia, Ukraine, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina.

- While China's strategy⁶ aims to achieve self-sufficiency in staple cereals, imports of basic feeds are expected to increase.

3% is Russia's share in China's imports due to the limited portfolio of exported agricultural products

Open sources, analysis by Yakov and Partners

MENA market

The MENA market has a capacity of about USD 125 billion, and a potential capacity of USD 130–150 billion. Russia's share in this market does not exceed 13%.

Thirteen percent is Russia's share of the MENA market, which has a potential capacity of USD 130–150 billion

- Food staples account for the largest share of MENA imports. It is about 23%, or USD 29 billion, of which USD 14 billion is wheat (purchases from Russia total USD 8 billion), USD 5 billion is sugar and molasses, and another USD 5 billion is rice, 80% of which is imported from India.

- Imports of basic feeds amount to about USD 22 billion (about 12% of imports are from Russia). In basic feed imports, corn accounts for USD 8 billion of imports, soybeans from Brazil and the USA for about USD 7 billion, barley for USD 3 billion, and soybean meal (mainly from Argentina) for USD 2.5 billion.

- About 16% of imports, or USD 19 billion, are animal proteins and dairy products, mainly beef (USD 5 billion), dairy products (USD 4 billion), poultry (USD 4 billion, of which more than two thirds are imports from Brazil), and fish (about USD 2 billion). Russia is not well represented in this segment.

- In addition, the region imports USD 16 billion worth of oils and oilseeds, of which about USD 8 billion is palm oil (mainly from Indonesia and Malaysia), USD 2 billion is soybean oil (from Argentina and Spain), and about USD 2 billion is sunflower oil (from Russia and Ukraine).

- The region will be fundamentally dependent on food imports, as climatic conditions will make it impossible to balance production and consumption of a growing population in the long term.

Southeast Asia (SEA)

SEA imports USD 100 billion worth of food from other macro-regions annually, of which USD 22 billion is supplied by China. Russia is virtually absent from the region: its contribution to regional imports is less than 1%.

The SEA region imports USD 100 billion worth of food annually, Russia's contribution is less than 1%

- The region's import structure is dominated by basic feeds, which account for about 20%. SEA countries are major consumers of soybean meal (USD 7 billion, mainly from Argentina and Brazil), soybeans (USD 5 billion, from Brazil, the USA, and Canada) and corn (USD 4 billion, from Argentina and Brazil).

- The region is also a major importer of dairy products (mainly milk powder from New Zealand worth USD 6 billion per annum), fish and seafood (USD 5 billion, mainly from China), beef (USD 4 billion, from India, Australia, Brazil, and the USA), and pork and poultry (USD 2 billion, from Latin America and the USA).

- Imports of food staples amount to about USD 17 billion, of which more than half is wheat (mainly from Australia), about USD 3 billion is sugar and molasses, and USD 2 billion is rice (mainly from India).

- China accounts for 40–60% of imports of fruits, vegetables and B2C products, and 25% of imports of highly refined products.

Sub-Saharan Africa

A region with relatively low imports (USD 43 billion). Russia's share is 2%. The main obstacle to increased imports is low purchasing power.

A key barrier to increased imports into Sub-Saharan Africa is the region's low purchasing power

- Food staples account for 36% of the region's imports (about USD 15 billion): rice imports – over USD 6 billion (mainly from SEA), wheat imports – about USD 5 billion (from Russia, the USA, France, and Canada).

- The region imports about USD 2 billion worth of poultry, the main suppliers being the USA, Brazil, and Poland. The region imports virtually no pork and beef.

- Sub-Saharan Africa’s palm oil imports total about USD 5 billion, while imports of other oils are insignificant.

- The region is characterized by slow import growth and limited purchasing power. Despite rapid population growth, the region finances food imports mainly through revenues from mineral exports, which has limited potential. Nevertheless, some countries (Nigeria, Angola, Congo, and Gabon) could be of interest for certain product groups.

The priority geographic regions for Russian exports are thus those countries of the Global South that are major net importers of food and have effective demand due to their developed economies and/ or coveted resources.

These are mainly China, MENA, Southeast Asia, and India. The total interregional imports of the selected target regions amount to almost USD 500 billion, of which Russia accounts for about 7%.

Export development: transforming the product portfolio

The President's Address to the Federal Assembly on February 29, 2024 outlined the goals for 2030: to increase exports of agricultural products by 1.5 times (up to USD 55 billion) and to ensure growth of domestic production by 25% from the 2021 level. According to our estimates, it may be difficult to achieve these goals if the average annual price level and the current structure of the portfolio of exported products remain unchanged, as well as in case of transition to less efficient technological solutions.

Our team's study, based on a consolidated agricultural market model and realistic estimates of target market shares, showed that changing the export structure in favor of higher-value products and implementing a national program of measures to reduce the end-to-end costs of agricultural products (“from field to port of destination”) could generate an export potential of USD 65–70 billion. Reaching this figure is an ambitious but achievable goal.

Russia's potential can be unlocked by changing the structure of agricultural exports and reducing end-to-end production costs

Drivers of production growth include expanding sown areas, increasing crop yields, and optimizing crop rotation, while export growth in monetary terms will depend primarily on the level of raw materials processing in Russia.

Wheat

Arable land could realistically increase by 5–6 million hectares to 85–86 million hectares in the medium term, resulting in no more than a USD 5 billion increase in wheat-equivalent exports. Agricultural and genetics technology could realistically increase Russia's average yield by 20% – up to 3.8 metric tons per hectare, resulting in total export growth of 25–30 million metric tons, or USD 6–7 billion. Russia will capture one third of the world wheat market, but further growth will be limited by both domestic capabilities and market capacity. This target is quite achievable as Russia has a sufficient advantage in the end-to-end cost of wheat.

Russia's wheat exports will grow by USD 6–7 billion if yields increase by 20%

Vegetable oils

Achieving export growth of USD 25–30 billion in the medium term will require a change in crop rotation in favor of higher-margin crops, taking into account demand (export market capacity and dynamics) and supply (objective capabilities of Russian producers).

Further development of oil exports will add USD 5–6 billion to supply:

- Sunflower oil exports can be increased by 1.6 times, to 6 million metric tons, which will increase Russia's export revenues by USD 3 billion. Russia's share of imports into friendly countries will be more than 75%, further growth will be limited by market capacity. The cost of sunflower in Russia is competitive, and production growth will require increasing yields through genetics and land improvement, as well as developing oil extraction and logistics infrastructure in the ports of the Azov and Black Sea basins.

- Exports of rapeseed oil are unlikely to exceed USD 2–3 billion (a growth of 0.6–0.8 million metric tons) due to the limited capacity of the target markets of China and SEA, wh ere Russia will reach a market share of 60–70%. If the geopolitical situation improves, further export growth is possible, driven by the EU.

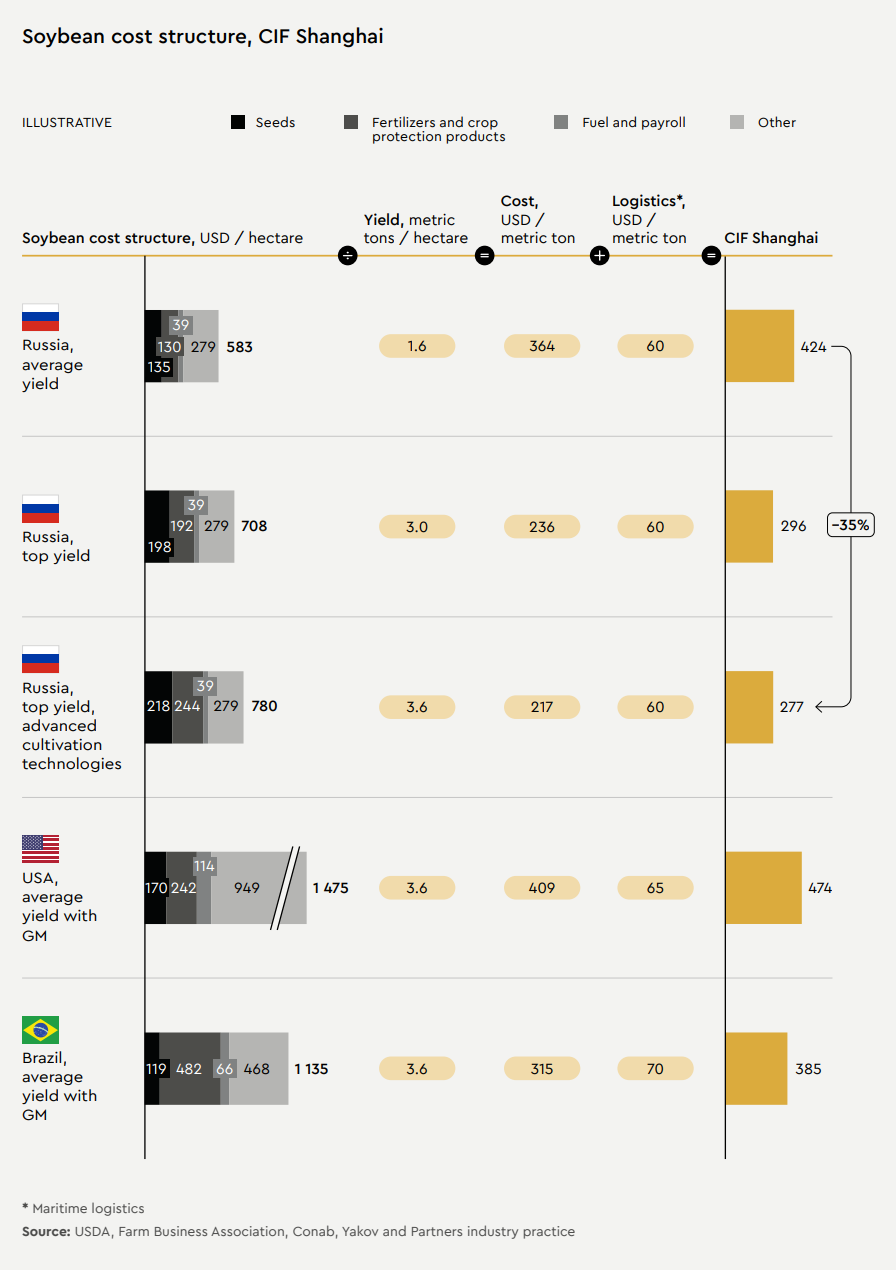

- Soybean oil exports could increase by about 2 million metric tons, or USD 2.5 billion, while Russia's share of imports into friendly regions, India and MENA, would be about 30% – against competition from Latin America. Russia is currently about 15–20% behind Brazil in soybean production costs due to higher yields in Brazil as a result of advanced agricultural technologies and genetics, including GM crops. Reducing the cost of soybeans is crucial not only for developing oil and meal exports, but also for making feed for animal protein production cheaper.

Further development of sunflower, rapeseed, and soybean oil exports will add USD 5–6 billion to supply

A change in crop rotation in favor of oilseeds will help ensure growth in their export volume and average export value per metric ton, as well as growth in the average EBITDA per hectare for agricultural producers. Successful competition in the global oilseeds market requires optimal production costs, which can only be achieved through the introduction of GM crops.

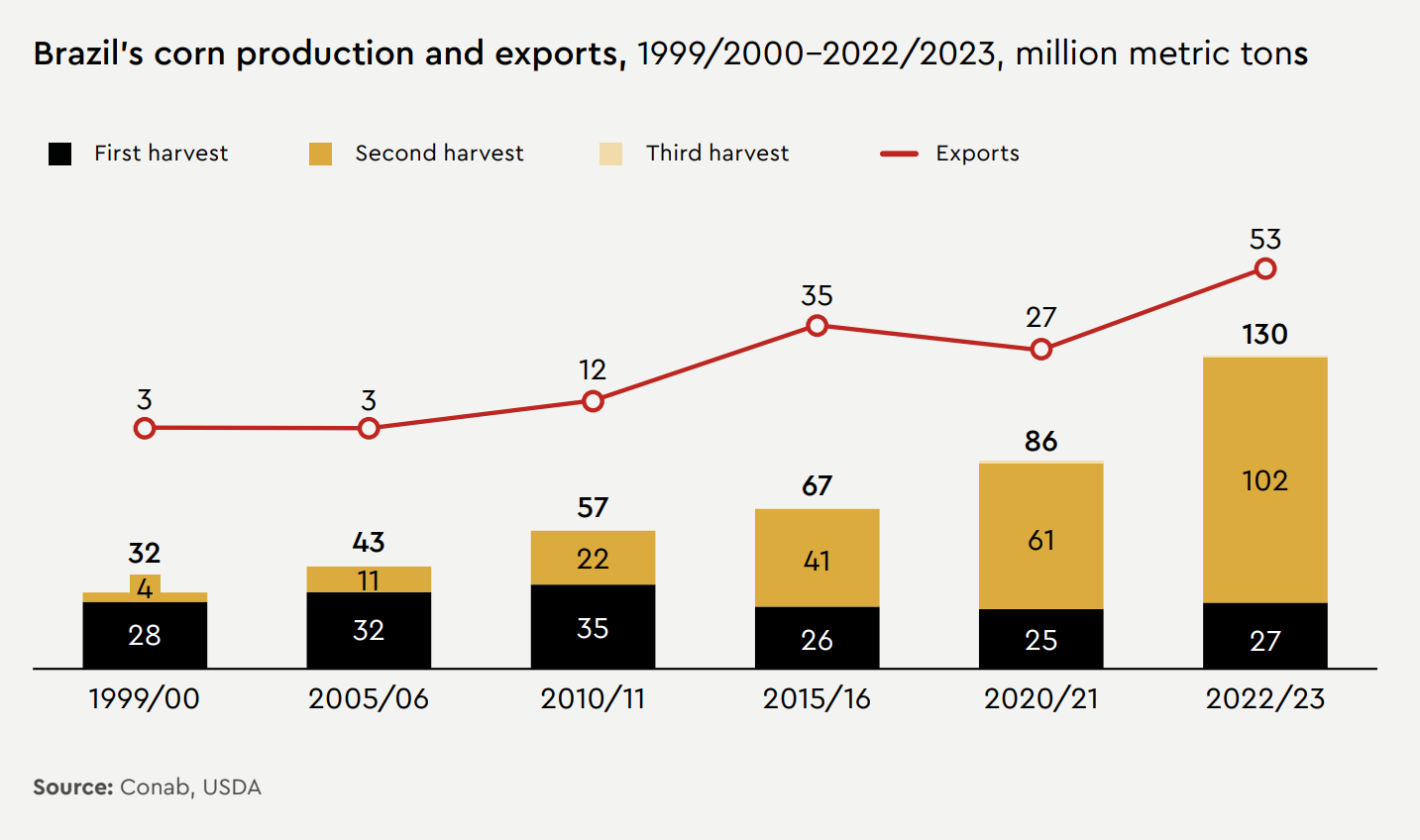

"The Miracle of the Cerrado": Brazil's agricultural revolution of the early 2000s

Two innovations enabled Brazilian farmers to successfully compete with US soybean and corn exporters in world markets.

- Development of soybean varieties for low latitudes using biological nitrogen fixation (BNF). The introduction of BNF soy alongside improved soil management practices in large-scale mechanized plantations led to rapid agricultural expansion in the savanna and increased exports.

- Adaptation of soy-corn double-cropping to the savanna. Farmers plant two crops in one season: first soybeans in October for harvest around February, and, immediately after the soybean harvest, farmers plant corn for harvest in May, June, and July.

According to most experts, the "Miracle of the Cerrado" was made possible by a combination of imported innovations, the talent and hard work of Brazilian farmers, and government agricultural and economic policies:

- First, the primary goal of the Brazilian government's agricultural policy has been to make the sector attractive for investment and to improve the welfare of the rural population. The transition to intensive agriculture has increased rural incomes, generated migration to low-income regions, boosted exports and tax revenues, and infrastructure development.

- Second, the introduction of BNF soy and double-cropping was only possible because of the complete opening of the market to foreign companies, which by the late 1990s controlled more than 90% of the country's seed market and offered the right hybrids and varieties.

- Third, the cornerstone of Brazil's agribusiness success is Embrapa's progressive policy of promoting the best agricultural inputs and technologies, including the use of genetically modified crops. More than 95% of soybean and corn acreage is planted with GM crops. Brazil is the second largest producer of GM crops in the world.

Basic feeds (meal, corn, and barley)

Basic feeds can generate export gains of USD 7–8 billion, of which about USD 5 billion will be for meal and USD 2 billion for corn and barley.

- An increase in sunflower meal exports by 1.4 million metric tons will increase exports by USD 0.4 billion. Russia's share in the target countries, China and MENA, will be more than 70%, against competition from Ukraine.

- Rapeseed meal can provide up to USD 0.7 billion, and Russia's share in friendly target regions (China, Thailand, and Vietnam) will be more than 60%. Competition in this market will come from Canada.

- Soybean meal production with the above increase in soybean oil output will amount to almost 9.7 million metric tons (at least 1 million metric tons will be used for feed to increase poultry and pork exports). Additional exports of soybean meal in this case will be about USD 5 billion, and Russia's share in friendly regions will be about 30%.

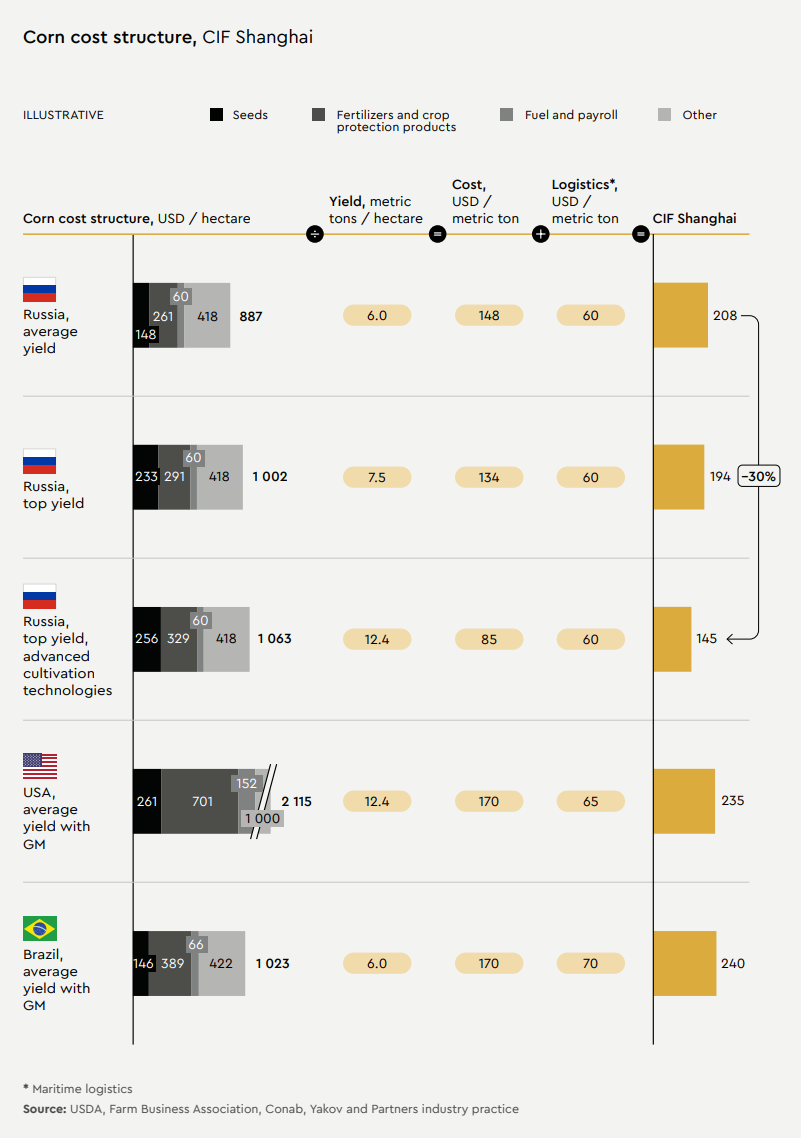

- The increase in corn exports could generate up to USD 1 billion. Russia's share could reach 10%, but a further increase in exports, despite the volume of international trade comparable to that of wheat, is not economically viable due to an even lower export price. Increasing yields and reducing the cost of growing corn is necessary for the domestic agro-industrial complex, primarily to develop the domestic feed base.

As in the case of soybean exports, competing in the world market will require active adoption of advanced agricultural technologies and the most productive crops

As in the case of soybean exports, our estimates show that competing in the world market will require active adoption of advanced agricultural technologies and the most productive crops.

7–8 USD billion could be an increase in the exports of basic feeds: meal, corn, and barley

Open sources, analysis by Yakov and Partners

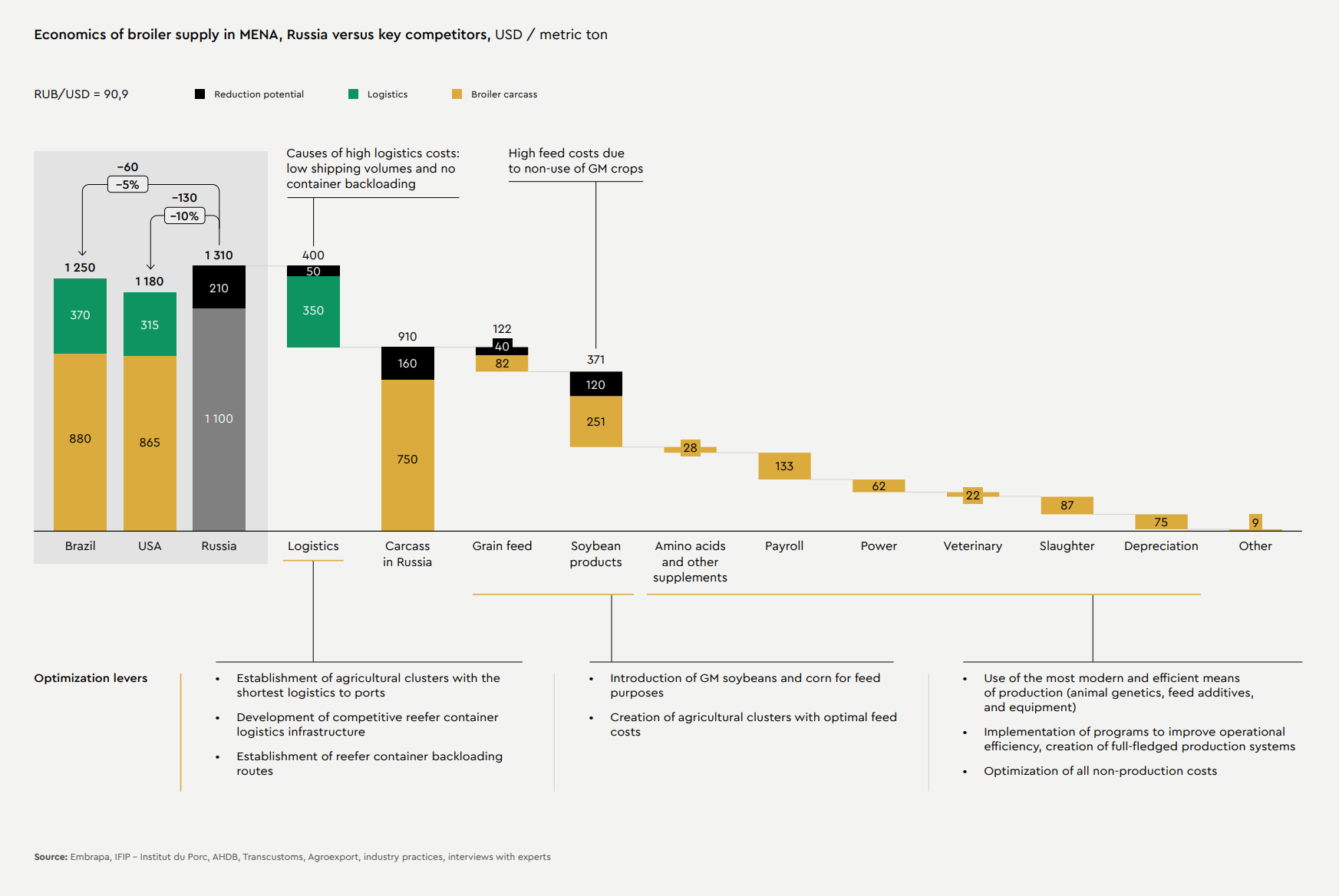

Animal proteins: broiler meat

USD 2 billion could be added to Russian exports by increasing the supply of broilers.

Broiler exports (including meat and by-products) total about 0.4 million metric tons per annum. To expand exports to 1 million metric tons, domestic production needs to increase by at least 1–1.5 million metric tons. In addition to achieving the necessary economies of scale, domestic production growth will help avoid the unpleasant dilemma of having to choose between domestic consumption and retail prices on the one hand, and maintaining market share in key export destinations on the other.

Reducing the cost of feed (mainly corn and soybeans) through the use of GM crops, providing unrestricted access to the world's best genetics and vaccines, making Russia a duty-free supplier to friendly target regions, and reducing the cost of multimodal logistics (with or without the elimination of the 100–150 USD / metric ton sanctions premium over time) will be key factors in increasing Russia's competitiveness in broiler production. All these measures should make it possible to conduct profitable export business while reducing the final price for the buyer to the level or lower than the main competitors (Brazil and the USA).

Animal protein exports from Russia can be made more competitive by reducing feed costs

Industrial broiler production offers obvious economies of scale by leveraging the best technologies and big data to improve production processes, standardize products, build export logistics and commercial operations. In this segment, the creation of "national champions" will have a visible impact.

The development of both export-oriented production (blast chillers, halal, small carcasses, etc.) and logistics is very capital intensive and requires single-digit interest rates for loans. This measure is particularly important for further production growth, as animal protein export is in most cases a less marginal channel than domestic consumption.

A realistic goal for Russian broiler producers is to capture 20% of imports in friendly regions – China, MENA, Sub-Saharan Africa, and SEA – against competition from Brazil and the USA.

4–5 USD billion is the potential growth of Russian exports through increased supplies of animal proteins

Open sources, analysis by Yakov and Partners

Animal proteins: pork

Higher pork exports will add USD 2 billion to Russia's agricultural export revenues.

If pork exports (meat and by-products) increase from the current 260,000 metric tons per annum to 1 million metric tons, the share of exports in the country's total pork production will increase from about 5% to about 20%. This is a significant risk that Canada is currently managing more or less successfully. Therefore, export growth will most likely have to be coupled with increased production for the domestic market, which seems a reasonable step given the consumption rates of animal proteins (meat, fish, and eggs) in Russia compared to developed countries.

As in the case of broilers, Russia's competitive advantage in pork will be driven by lower feed costs (mainly corn and soy) through the use of GM crops, unrestricted access to the world's best genetics and vaccines, Russia becoming a duty-free supplier to friendly target regions, and lower multimodal logistics costs (with or without the removal of the sanctions premium over time).

The capacity of Russian slaughterhouses appears to be sufficient to support export growth, so subsidizing the interest rate to bring it down to single digits will be needed mainly for the construction of breeding farms and the development of blast chilling facilities.

Development of animal protein exports requires subsidizing the interest rate to bring it down to single digits

The capacity of pork export markets is smaller than that of poultry markets. If production is increased by 1 million metric tons, Russia's share of exports to target geographical regions – mainly China (more than 70% of imports by friendly countries), the Philippines and Vietnam, now dominated by Brazil and the USA – will be about 40%.

Other

Other products and technologies could add USD 2–3 billion to total revenues.

- We estimate that exports of milk powder to China can be increased by 2 million metric tons of milk equivalent. If production of finished products reaches 200,000 metric tons per annum, Russia's share in China's imports will reach 10–15%. In addition, there is a potential to increase exports of confectionery products to China by 50,000 metric tons. If this potential is realized, Russia's share in imports of this product category will be about 30%. Export potential can also be seen in the supply of finished dairy products.

- Increasing exports of flour and other B2C products to the MENA region by 1 million metric tons will increase Russia's share of this region's imports to 30%.

Milk powder exports to China can be increased by 2 million metric tons of milk equivalent

The growth of fish and seafood exports in the near future will be limited by fishing quotas, while exports of highly refined products and cattle meat will be limited by Russia's lack of competitiveness in this area.

Conclusion. Uplift levers

Russia's agricultural exports have been growing steadily for many years, and Russia now ranks 6th among the world's largest food suppliers in terms of volume. So far, however, volume growth has been driven mainly by cheap grain. We estimate that the export growth potential within the current portfolio of the agricultural sector is USD 8–10 billion at multi-year average prices. Continued active growth of the agro-industrial complex is possible mainly through exports, but no changes to the current product portfolio, limited access to modern technologies, and fewer measures to support private investment will result in exports reaching a plateau by 2025–2026.

Further export growth in monetary terms requires a structural shift to higher-value products, primarily animal proteins, soy-based feeds, and highly refined products. To enable this transition, the following challenges need to be addressed:

- Ensuring the growth of the gross harvest of major crops by 50–60 million metric tons by increasing the area under cultivation and yields by 15–42% for various crops.

- Changing the export structure in favor of products with higher added value, especially animal feed and animal proteins. This will require a change in the country's crop rotation structure in favor of feed crops.

- Reducing the unit cost of priority export products, primarily protein, to a level on par with or lower than that of major competitors, by constantly and consistently optimizing the unit cost of production (economies of scale), using the best technologies (genetics, including GM crops for feed and export supplies, vaccines, crop protection agents, machinery and equipment, land improvement, cultivation technologies), developing the logistics infrastructure and preventing its monopolization, providing financial support to agricultural producers, minimizing internal administrative barriers, and maintaining a price advantage for domestic agricultural producers in terms of fertilizers, energy, and other inputs and consumables.

- Improving the animal health environment and addressing plant pest threats, which, in addition to regional biosecurity measures, will require unrestricted access to the best vaccines and crop protection products.

- Introducing regulatory tools to maintain industry margins in an environment of structural production overcapacity for the domestic market, which will require new approaches to regulation and management of interaction between the Ministry of Agriculture, industry associations and agribusinesses.

- Removing administrative barriers to access to target markets set by the regulatory authorities of importing countries (quotas, tariffs, unjustified sanitary restrictions, etc.). This seems to be the most difficult of the above tasks, as it is linked to foreign policy and the state of the trade balance with each country.

Reducing the end-to-end cost of production "from field to port of destination" will be a key driver of export growth

The Russian agro-industrial complex and the regulator must create and then learn to exist in an environment of structural production overcapacity

Systematic and coordinated efforts of the regulator and the industry in all areas will be a key success factor. We believe that all these tasks can be described in one phrase: increasing the investment attractiveness of the agro-industrial complex. Solving the problem so framed will naturally lead to the solution of all other problems: increasing labor productivity and reducing production costs, developing the production and export of agricultural products, increasing wages and the attractiveness of the industry as an employer, reducing food inflation, and other problems that today seem difficult and sometimes even mutually exclusive.

The basis for solving all challenges and problems of the Russian agro-industrial complex is to define the goal in terms of "ensuring investment attractiveness of the agro-industrial complex and acceptable margins"

The use of the best agricultural technologies and genetics is impossible without international cooperation. As we have already described in our study, the creation of a major world-class genetics player in the Russian agro-industrial complex using our own resources would require decades, significant investments, and scientific expertise that is not available in sufficient supply. The way out may be to buy a foreign company or to cooperate with suppliers from friendly countries (GDM in genetics, Stara in agricultural machinery, etc.).

World experience shows that in order to be successful in international trade it is necessary to create large national companies capable of consolidating large volumes of products and providing economies of scale in production, logistics, and marketing of products. So far, the leaders of the Russian agro-industrial complex are several times smaller than the global leaders.

The structure of a "national champion" deserves a separate discussion: although the current dominance of corporations in global agricultural trade is obvious, there are cooperatives in the world with revenues in billions of dollars, and in the past large government agencies in the form of marketing boards have been very successful in managing export development.

To succeed in international trade, "national champions" must be created

We do not see a contradiction between the goal of increasing the industry's investment attractiveness and technological sovereignty, but rather the opposite. If we define technological sovereignty as having access to all the necessary technologies in the most complex realistic scenarios, then, as our study shows, the optimal solution becomes obvious if the investments in the form of labor and capital necessary to create technological sovereignty in various areas of the agro-industrial complex are adequately assessed. It may consist in buying foreign companies and their further development in the Russian market, creating stable logistic routes from countries with different geopolitical agendas, using local solutions that are isolated from the industry until the Time X in case of their low efficiency, and, perhaps, in other options or a combination of them.

The key to achieving the new ambition is to correctly define the objective in terms of promoting the investment attractiveness of the agro-industrial complex and public welfare, and to properly assess the economic realities.

Notes

1 http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/assignments/orders/73759

2 https://yakovpartners.ru/publications/national-champions-in-agriculture/

3 https://yakovpartners.ru/publications/a-sovereign-capability-in-genetics-for-russian-agriculture/

4 Excluding intra-EU trade.

5 The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is the geographic region that comprises the countries of the Maghreb and the Middle East.

6 The Food Security Act went into effect on June 1, 2024.