To enhance the operational, financial, and economic performance of Russian agriculture, it would be feasible to focus on providing the sector with high-quality genetics. Targeted acquisitions of one or more foreign genetics firms with world-class capabilities and expertise by leading domestic companies are a quick and effective way to ensure close-to-complete import substitution for key agricultural crops. Conversely, attempting to accomplish this mission on one's own could be significantly more costly and take several decades, resulting in only a modest success.

1,2-1,7 USD bn - potential import substitution of genetic technologies in Russia by 2035

Open sources, Yakov and Partners analysis.

To increase the annual economic returns from the domestic agricultural sector by USD 40 bn, it is vital for Russian companies to reach a new scale of operations. As shown in our previous research, the resources for growth can only be secured through IPOs of major Russian agricultural companies and their subsequent "upgrade" to the level of global leaders in key agribusiness areas. Unless the development tasks are addressed, under the optimistic scenario, export-led growth of the domestic agricultural sector would hit a plateau, and, if the risks (e.g. sanctions) are realized, the country could start losing its share of the global market.

Genetic technologies are a key growth driver for the Russian agricultural sector. Creating several Russia-based national champions with ample resources would settle the yet-unresolved issue in domestic agriculture – to build a genetics industry that would be both sovereign and competitive in the global market – before 2035. According to our estimates, by 2035, this would enable Russia not only to "localize" most of the imported genetic technologies (we estimate the potential import substitution for all agricultural inputs at USD 2.4–3.4 bn, including USD 1.2–1.7 bn for those related to genetics) but also to make a significant contribution to the future exports of producer goods in the amount of USD 0.6–1.3 bn a year. This development could be driven by the acquisition of one or several foreign market-leading genetics companies and their integration into a system of joint ventures, partnerships, and cooperatives – primarily within the BRICS countries.

What depends on genetics (and other inputs) in the agricultural sector?

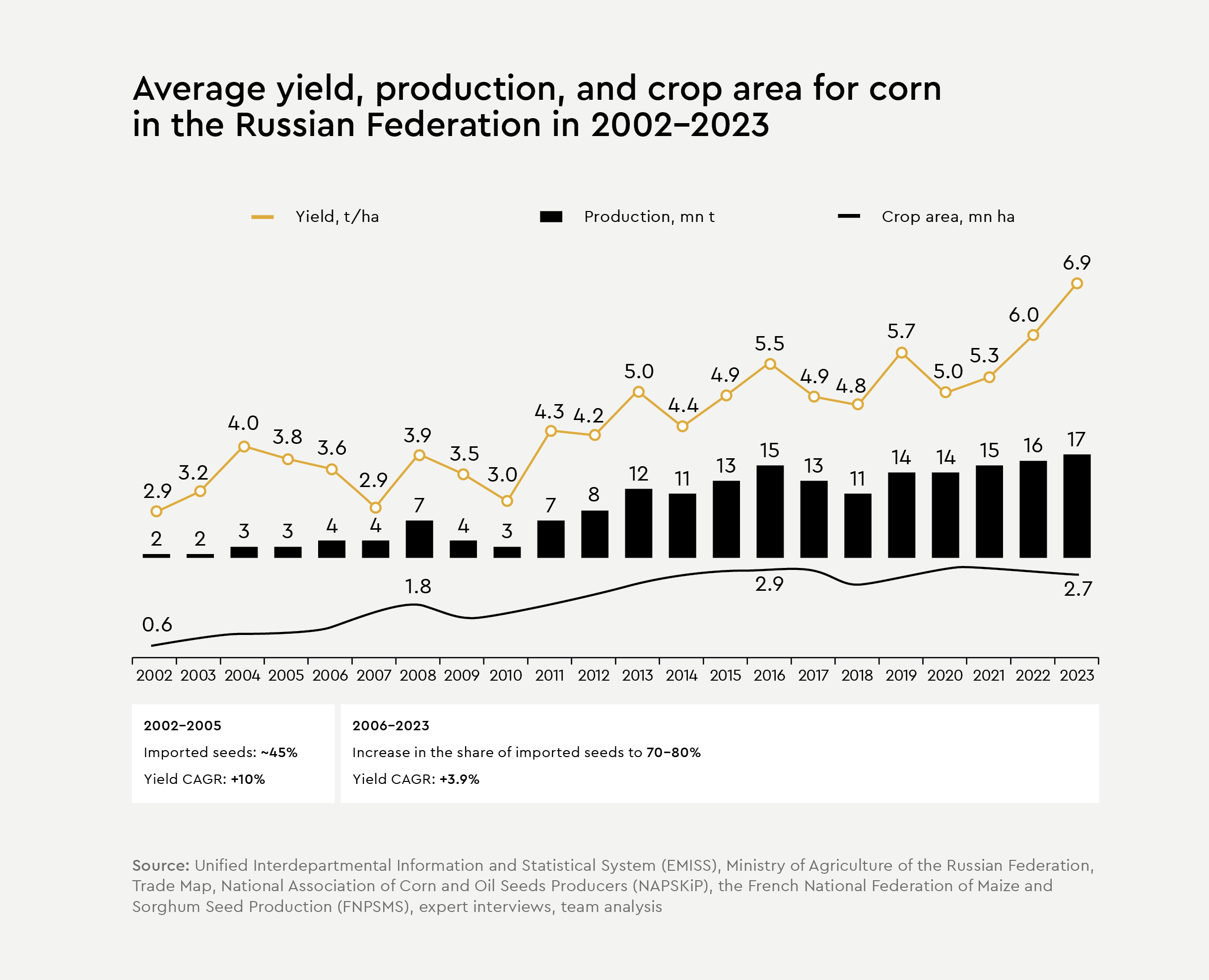

Since the 1940s, when the utilization of efficient means of production began to spread in the US, the corn yield in the country has increased by an order of magnitude, from 1.5 to 11.9 t/ha by 2023.¹

For the same reason, which is the active adoption of new technologies, the average yield of corn for grain in Russia has grown from 3 to 7 t/ha over the past 20 years.

What drives the yield?

Yield growth in agriculture is the result of a complex combination of numerous factors. These include plant genetics, use of fertilizers and crop protection products, advances in agricultural machinery, accumulation, codification, and application of knowledge about best farming practices, and finally, digitalization.

The result of this combination is governed by Liebig's law of the minimum.

This law states that the most significant factor is the one that deviates the most from its optimal value. This principle is often illustrated by Liebig's barrel: if you pour water into a barrel, it can rise only as high as the shortest stave, making the lengths of the other staves irrelevant.

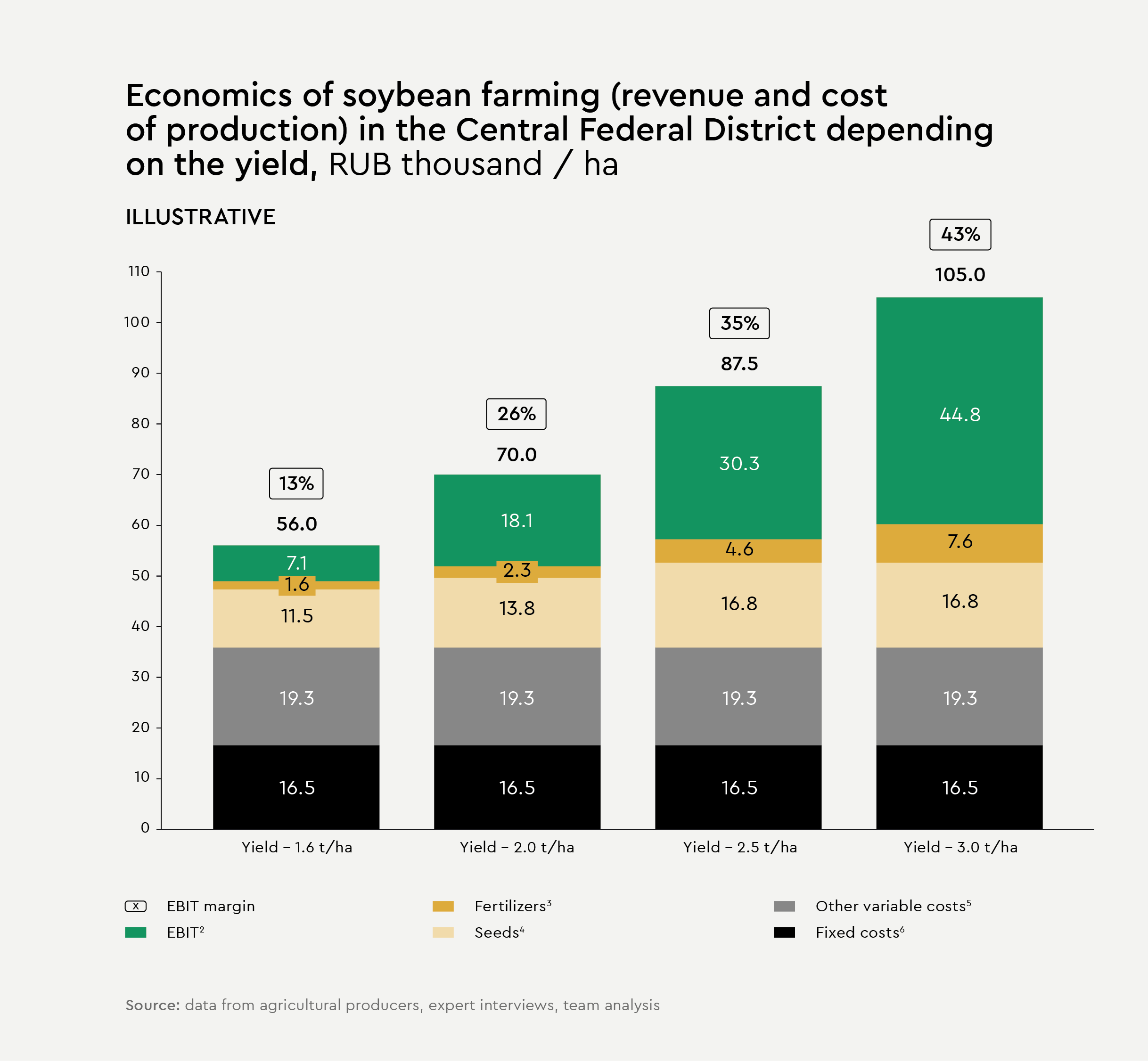

Thus, in order to make agriculture highly productive (and highly profitable), it is essential to ensure that all high-quality factors, without exception, are in place. Among these, genetics is an essential link in the chain that determines the theoretical maximum yields and quality characteristics of crops. This is important because a significant share of agricultural expenses is fixed, and even a slight increase in the yield leads to substantial growth of operating profit.

In terms of operational management, plant cultivation represents a complex combination of bottlenecks which are geographically concentrated in the place of cultivation, and a critical project path with predetermined start and completion dates and minimal opportunities to make adjustments. Therefore, operational expertise in logistics, sales organization, procurement, maintenance and repairs, and other functions has a significant impact on the financial performance of the agricultural sector.

The same logic applies to animal protein genetics and its impact on operational and financial performance of companies.

Why does Russia need a sovereign capability in agricultural genetics?

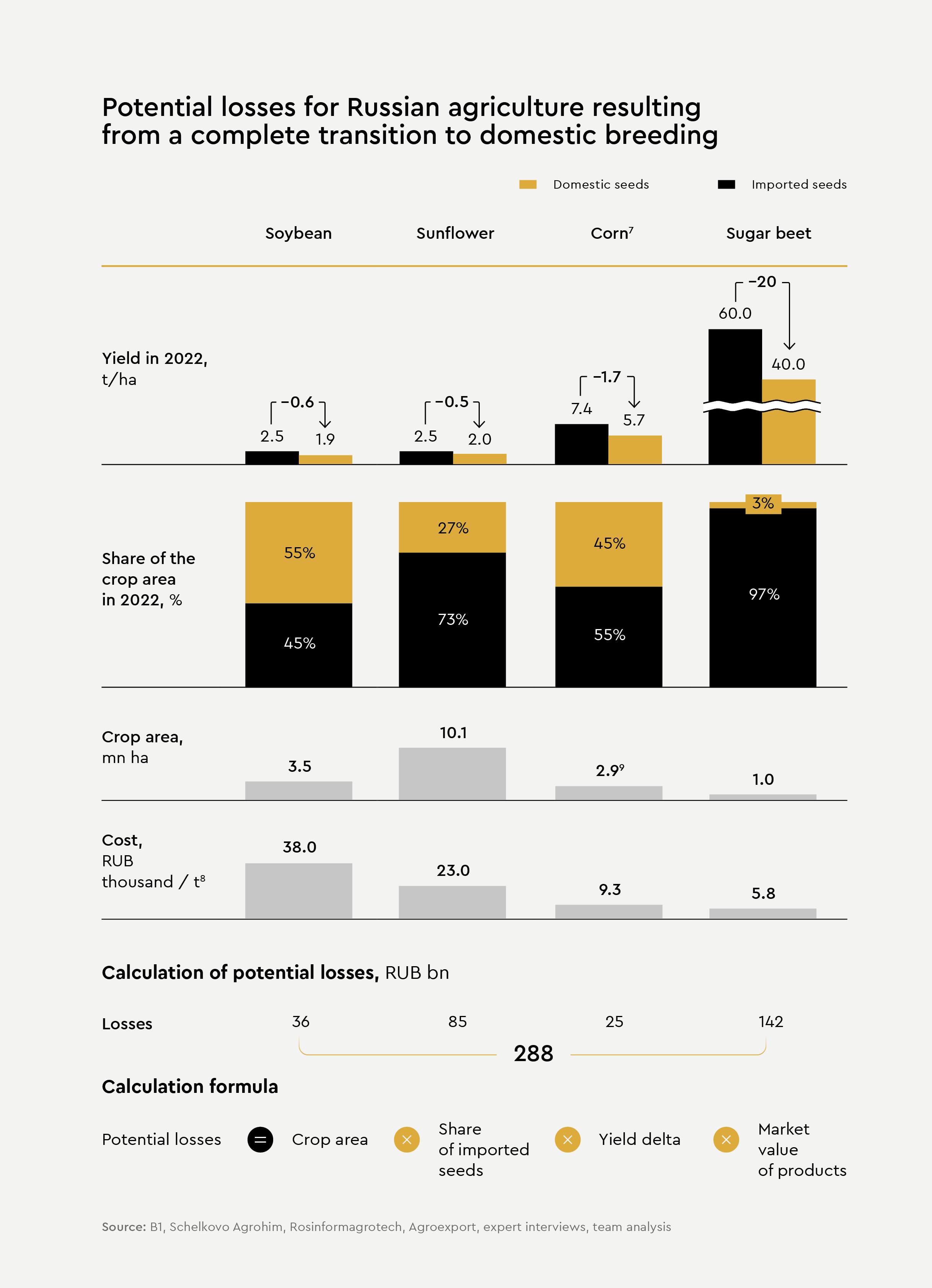

Currently, the efficiency of Russian agriculture heavily depends on foreign agricultural inputs – seeds, animal genetics, crop protection products, equipment and machinery, and digital solutions. Except for wheat and barley, a significant portion of the seeds used in the Russian agribusiness are imported. The yield of domestic soybean, sunflower, corn, and sugar beet seeds is 20–30% lower than that of foreign ones.

If the transition to domestic seeds in these crops happened right now, it would cost Russia approximately RUB 300 bn annually. These RUB 300 bn of net loss resulting from low efficiency (corresponding to 3.6% of the total agricultural production in Russia) would have to be shared between consumers (in the form of higher prices) and producers (as lost profits). In such event, efficient farms using state-of-the-art technologies would be the most affected.

If the transition to domestic soybean, sunflower, corn, and sugar beet seeds happened right now, it would cost Russia approximately RUB 300 bn annually

Although there have been no significant restrictions in the agricultural sector so far, the likelihood of sectoral sanctions on Russian agriculture cannot be assumed equal to zero. For example, in 1990, the US imposed restrictions on the import of technologies and goods to Iraq, which led to a food crisis. In 1991, an import and export ban was imposed on Haiti; in 1992, restrictions on Cuba were tightened, and so on. Although the EU and the US have not formally declared any intention to sanction Russian agriculture, their overall actions suggest that global sanctions indirectly targeting the Russian agricultural sector could threaten national food security:

- Virtually every major Russian fertilizer producer is subject to sanctions, same as a significant share of the equipment they need.

- The EU sanctions adopted in 2022 banned the import of some components for agricultural machinery. Consequently, Russian farmers faced a shortage of spare parts for foreign-made equipment, which accounts for 30–40% of the Russian fleet of agricultural machinery.¹⁰

- The No Russian Agriculture Act, which was passed by the House of Representatives on January 12, 2024, mandates that the U.S. Department of the Treasury instructs the country's representatives at international financial institutions to "use the voice, vote, and influence of the United States" to support projects that decrease the reliance of specific countries on Russia for agricultural commodities, particularly fertilizer and grain.

The likelihood of sectoral restrictions on Russian agriculture cannot be assumed equal to zero, and domestic genetics lacks the means to respond to a global threat

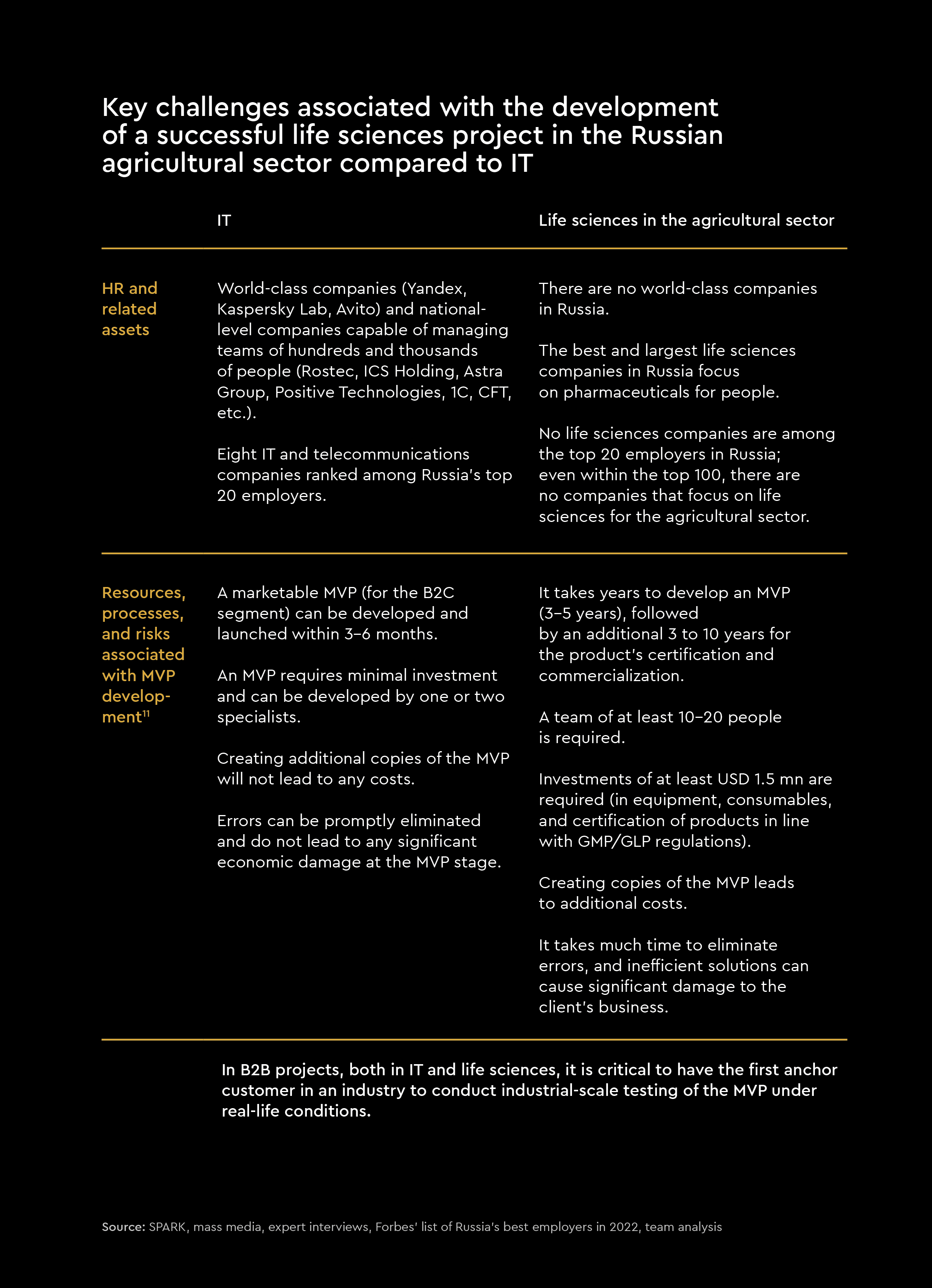

In these circumstances, one of the key problems is that domestic genetics lacks the means to respond to a global threat. Russia's inheritance from the USSR did not include assets in life sciences that are significant on a global scale. For both objective and subjective reasons, over the past 30 years, the country failed to establish a solid R&D base for Russian agriculture or achieve any significant results in the field.

The results are clear: over the past 15 years, Russia has successfully developed an ecosystem of digital services and equipment – the country's own technological solution that addresses national security issues (and yet fails to ensure 100% import substitution at all process stages). This includes:

- Computing and networking equipment based on domestic processors (SoC) with licensed and/or independently developed RISC-V and ARM cores;

- An operating system based on the Linux kernel with Russian software, including information protection tools, database management systems, geographic information systems, office productivity software, etc.;

- Application software (business applications) based on programming languages and open frameworks that are not subject to patent or licensing restrictions;

- A large group of integrators capable of designing and creating information systems based on Russian components in line with the intended purpose and target level of protection.

It has solid protection against risks such as quotas, tariffs, and other import restrictions on technologies, since it uses means of production that cannot be remotely restricted or banned, and this ecosystem's output can be developed through the joint efforts of its participants (for example, the collaboration of Russian companies to develop an independent branch of the Linux kernel at the core of the operating system). In addition to that, many components can be sourced from multiple countries.

However, Russia lacks the markets (top Russian life sciences companies focus on pharmaceuticals rather than the agricultural sector), time, and resources (which must be substantial) to develop the country's own ecosystem for genetics.

Unlike the ecosystem of genetics, which the country cannot develop due to a lack of resources and time, the Russian ecosystem of digital services and equipment is resilient to external restrictions

Thus, even if we speak about creating a single world-class genetics company rather than building the entire ecosystem for genetics from scratch using the country's own resources only, it would take decades and require large investments, and, just as important, high-quality scientific resources, which are currently insufficient.

However, it is important to note that Russia is not the only major agricultural power that found itself in such a situation.

20–30% - lower yield of domestic soybean, sunflower, corn, and sugar beet seeds compared to foreign ones

Open sources, Yakov and Partners analysis.

Economic landscape of the global plant genetics

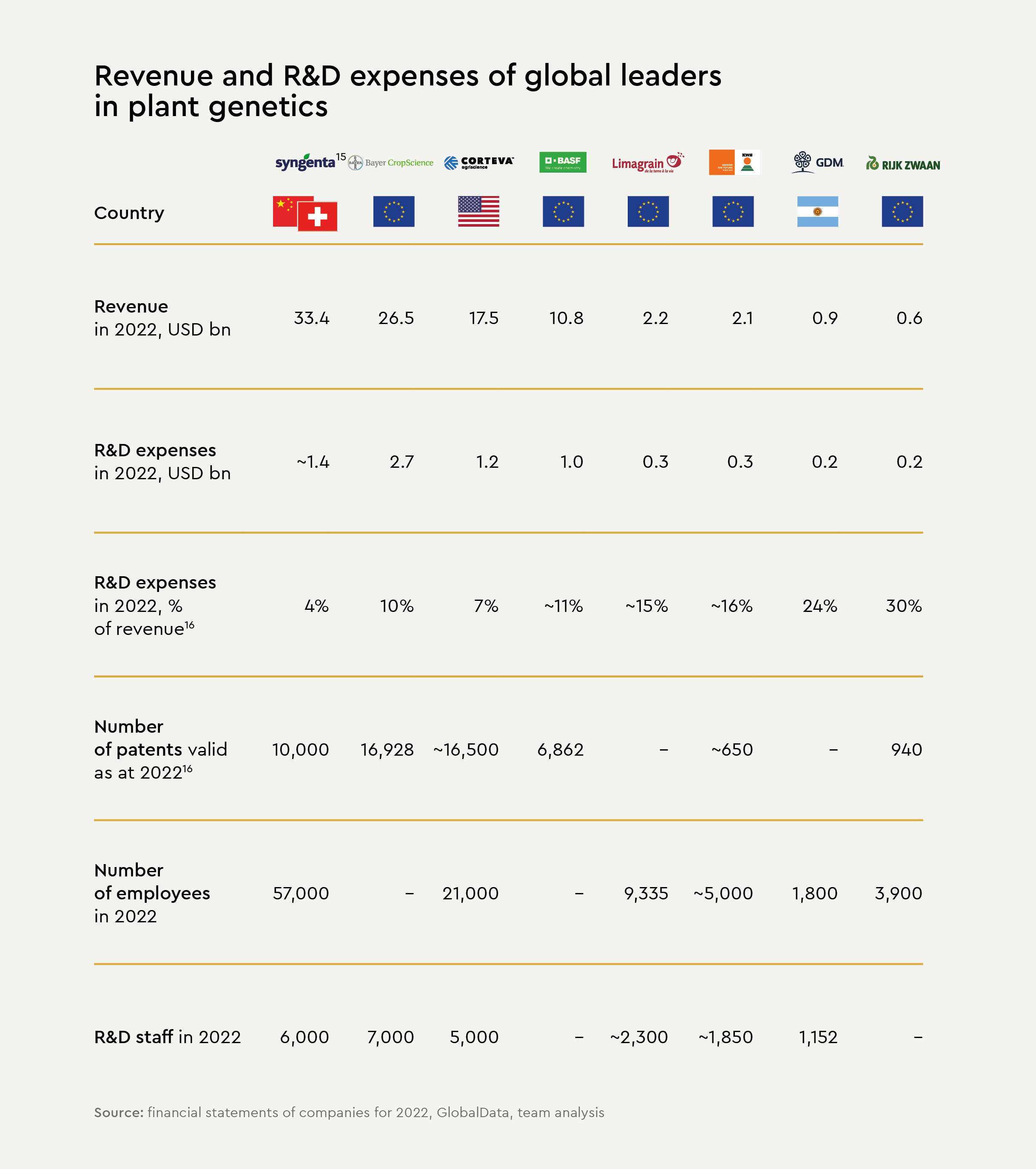

Global experience shows that a major player with sustainable economic performance in plant breeding is a company with a revenue of at least USD 100 mn and access to more than 10% of the global market.

This is due to the fact that success in the plant genetics business is determined by three key factors:

- Genetic material and the availability of a comprehensive database of selection results accumulated over decades and based on as many experiments as possible;

- Accelerated breeding methods and technologies, including not only gene technologies (gene marking, genotyping, CRISPR-Cas, etc.) but also phytotrons, greenhouses, and open-field sites in both hemispheres and at various altitudes above sea level, etc.;

- Industrial-scale seed production technologies.

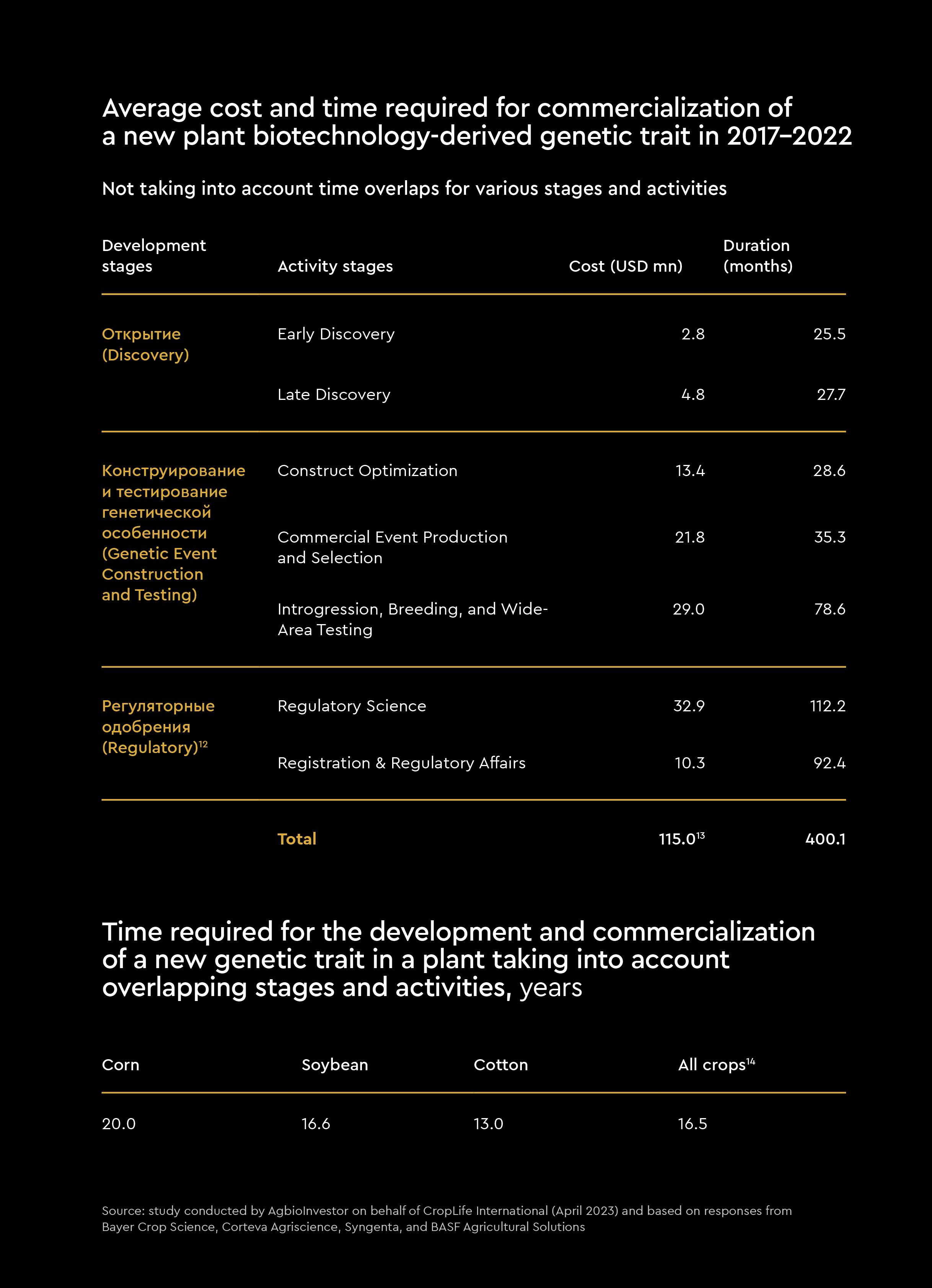

Developing a new trait in a single plant takes 15–20 years and costs USD 115–136 mn for all phases from discovery through construction and testing to obtaining regulatory approvals.

Developing several commercially viable hybrids costs companies tens of millions of dollars a year for testing thousands of experimental varieties.

Actual cost and duration of R&D projects have led to the emergence of a group of global leaders that offer a full range of products and services to agronomists (seeds, crop protection products, consulting, and IT solutions) and generate revenues in the tens of billions of dollars, with seed sales alone accounting for USD 2-5 bn. There is also a "peloton" of mid-sized companies with revenues of USD 100–300 mn. Average revenue of each of these twenty relatively small companies from different countries is approximately USD 200 mn. Building these companies took decades, which Russia cannot afford.

It should be noted that the governments of several countries have attempted to create high-yield hybrids and varieties. In general, they have been noticeably less effective. For example, since 2002, the Indian state-owned company Mahyco has been distributing Bt cotton created by a joint venture between Mahyco and Monsanto. This hybrid had shown decent performance until 2008, but then its yield became lower. Experts suggest that local plant breeders might have underestimated a whole range of factors, such as the pests' ability to adapt to the new variety and the complexities of the monsoon climate. Other causes included frequent failures of Indian farmers to use the right sowing techniques and the lack of capacity on the part of Indian government plant-breeding agencies to adapt the hybrid to changing conditions. For comparison, the US, Australia, and China, which use BASF versions of the Bt hybrid that are upd ated on a regular basis, do not have that problem with yield.

Developing competitive genetics takes decades and requires significant investments, while attempts to create highyield hybrids and varieties are often less effective

However, this can be viewed as a special case of the general rule that the best results are achieved when the seed producer's financial success is entirely dependent on the financial success of its consumers.

It should be noted, however, that not all crops are dominated by large companies. For example, according to Kynetec, in 2022, the commercial segment's share of the global market for wheat, barley, and sorghum was approximately 30%, while that for corn and rapeseed was 80–90%, and for cotton, sunflower, and beet it was close to 100%. This is due to a number of factors such as seed unit weight, the ability to create high-yield hybrids and/or cost and complexity of seed replication, genetic diversity, and other characteristics of a specific crop. This explains, for example, why Russia is nearly self-sufficient in terms of high-yield genetics for wheat, barley, and rye.

China's experience

China's agricultural sector faced a similar situation to that of Russia. Despite a vast market, strong and continuous demand for agricultural products, and a well-developed agricultural sector with sufficient production capacities, China's genetics industry was inefficient and technologically obsolete. Yields of China's key crops such as soybean, corn, and wheat were but a fraction of those in developed agricultural markets.¹⁷

Although the Torch Program launched in 1988 by China's Ministry of Science and Technology to promote high-tech development across various industries was an obvious success, there was no significant progress in advancing its agricultural genetics.

Eventually, Chinese state-owned companies, which lacked advanced genetics capabilities, bridged the technological gap by acquiring industry leaders that had the necessary expertise and intellectual property. In 2011, China's largest state-owned agrochemical company ChemChina acquired a 60% stake in Israel's ADAMA, one of the largest suppliers of generic crop protection products, for USD 2.4 bn (and purchased the remaining 40% in 2016). In 2017, ChemChina made a blockbuster deal to acquire Syngenta, a Swiss-based company with an annual revenue from seed breeding and agrochemicals close to USD 13 bn. The USD 43 bn deal was a record for the Chinese agricultural sector. Almost 90% of that amount was financed through loans from state-owned banks and the issuance of bonds.

China bridged the technological gap in agriculture by acquiring leading foreign companies, thereby ensuring technological sovereignty and economic growth in its agricultural sector

The acquisition turned out to be beneficial for both parties. Its advantages for Chinese producers included access to advanced herbicides and pesticides to improve performance and reduce the impact on soil, and creation of a robust base for scaling up production, while Syngenta managed to enter the vast Chinese market without regulatory hurdles and secured investments to establish R&D centers and production facilities in China.

As a result, Syngenta's revenue increased 2.6 times within five years after the acquisition, and the Chinese giant ranked among the top 200 companies of the Fortune Global 500 list. The success of this deal opened a window of opportunity for the Chinese agricultural sector to make M&A deals with leading European and American companies, ensuring technological sovereignty and sustainable financial and economic growth for China’s agricultural sector.

100 USD mn – minimum turnover of a major player with sustainable economic performance in breeding

Open sources, Yakov and Partners analysis.

Russia's way forward in crop farming: acquiring and developing a BRICS+ scale genetics player

Analysis of today's global market shows that the most attractive path for future development of Russia's plant breeding is the acquisition of mid-sized private companies with strong positions in international markets and robust expertise in genetics from Europe and other regions.

These companies typically:

- ...have revenues of USD 100–200 mn and an extensive sales footprint spanning 10 to 70 countries;

- ...test new genetic traits in plants, gather data in global markets, and maintain extensive databases that have taken decades to build;

- ...spend millions or tens of millions of dollars annually on research and development to maintain a competitive edge in genetics;

- ...focus on multiple crops, including genetic technologies for sunflower, sugar beet, potato, soybean, corn, and various vegetables that are the most relevant for Russia;

- ...have already built extensive networks of contacts and partnerships with leading universities and companies worldwide.

A well-prepared deal with an optimal make-up similar to the ChemChina/Syngenta case creates merger synergies. A foreign company with expertise in seed genetics would get a chance to capture nearly 100% of the Russian market for most crops, while the Russian party would have new prospects, including opportunities to enter new sales markets in the BRICS+ countries. For example, the BRICS+ market for sunflower seeds is 2.5 times larger than the Russian one; for sugar beet, 3 times larger; for soy, 33 times larger; for corn, 53 times larger; and for vegetables (tomatoes, onions, carrots), more than 160 times larger. It seems optimal and logical that a portion of the costs related to the acquisition of a leading genetics company should be borne by the BRICS+ partner.

Thus, while creating a world-class plant breeding major in Russia would take several decades and require enormous investments (including those in scientific resources which are currently lacking), the acquisition and development of an existing company (or several companies) for the ultimate purpose of building a sovereign capability in genetics and plant breeding can cost USD 1–1.5 bn, assuming a revenue multiple of 2–3.

Global experience in animal protein genetics

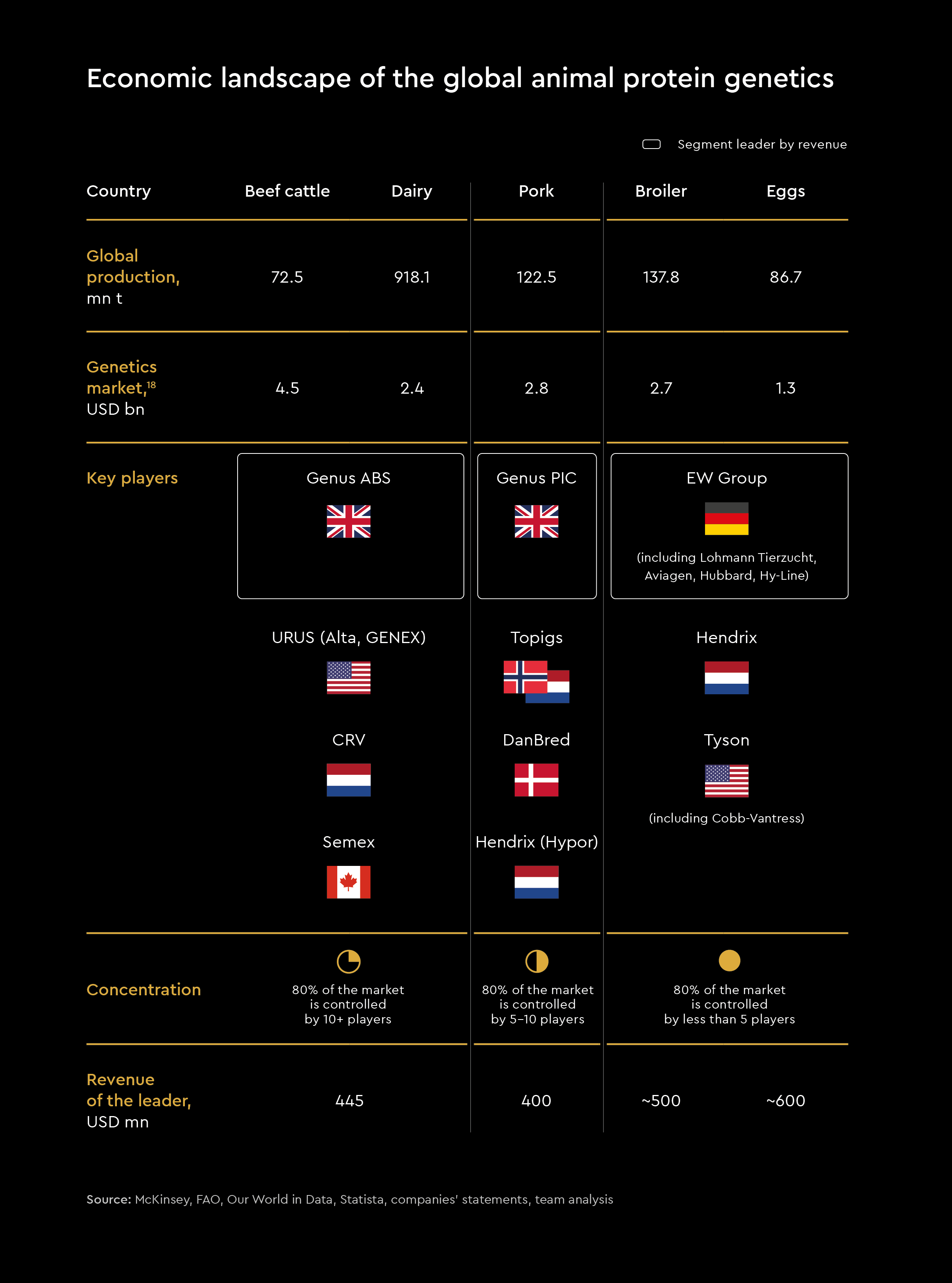

The economic landscape of the global animal protein genetics market is primarily defined by the number of descendants a purebred progenitor can produce, and, similar to plant breeding, by databases of breeding results, availability of production assets in different countries (including for biosecurity purposes), and breeding technologies.

Consequently, the global cattle genetics market is highly fragmented, while the production of pure lines in broilers and table eggs is rather concentrated.

Just like in plant breeding, the animal protein genetics market also has its leaders and contenders. For example, the undisputed number one in swine genetics is the British company Genus PIC; however, there are also some ten smaller companies with annual revenues of USD 100–200 mn.

Joint ventures instead of acquisitions

The situation in Russian animal genetics is very much similar to that in plant breeding but it has some notable differences. Also, there are some differences across the market segments. For example, Russia's own cattle population is 1.9 mn, so the country's reliance on imported breeding stock for cattle is relatively low, less than 25%. However, experts note a shortage of high-yielding bulls and their semen.

Russia is still almost entirely dependent on imported genetic material for broilers: the share of the Smena-9 domestic crossbreed is approximately 5%, with the remaining market dominated by foreign companies Cobb and Aviagen (Ross).

The cost of errors in selecting cross broilers is extremely high: choosing a less efficient crossbreed can lead to a 20% reduction in the chick output, even assuming that the cost of a se t of hens and roosters is the same. Thus, even if there are no differences in FCR¹⁹ and other KPIs, substituting Aviagen crossbreeds with less efficient ones could reduce the industry's annual operating profit by RUB 15–20 bn. Using an even less efficient cross with a lower growth rate than that of the Ross product would exacerbate the damage even more. This difference would represent a net loss resulting from low efficiency and would have to be shared between consumers and producers.

As much as 95% of Russian broiler production is dependent on imported genetics. Addressing this situation will require significant time and investment: an immediate substitution of Aviagen crossbreeds with less efficient alternatives could reduce the industry's annual operating profit by RUB 15–20 bn

That provided, creating a major high-quality genetics player for nearly all animal proteins is only feasible in a market that is much larger than the Russian one. Russia's share of the global livestock production varies by category, from 2.2% for cattle to 3.8% for broilers. In these circumstances, the markets of the BRICS+ countries are many times larger (14 times for cattle and dairy, 7 times for pork, and 17 times for broilers and eggs) and much more attractive.

A Russian animal genetics company focused on international markets could be created through the acquisition of a mid-sized specialized company from Europe. This approach has also been tested by the Chinese agribusiness:

- In July 2017, CITIC Agri Fund and Beijing Capital Agribusiness acquired 100% of shares in the British-based Cherry Valley Farms Ltd, marking the first international acquisition by a Chinese livestock business. This deal secured a 75% share of the global Pekin duck breeding market, increased China’s self-sufficiency in primary poultry breeding, and facilitated the creation of a high-quality breeding program and the healthy development of China's livestock production industry.

- Genus, the parent company to the British-based PIC, formed a strategic partnership with Beijing Capital Agribusiness (BCA), a Chinese state-owned company, to distribute PIC's genetics in China.

Most mid-sized European and American companies (earning annual revenues of USD 20–250 mn) with expertise in pure line breeding are organized as cooperatives. This hinders their takeovers but facilitates other forms of collaboration, such as joint ventures. Another example of this (apart from the Genus and BCA partnership) is the joint venture for 5,000 GGP animals between the French cooperative AXIOM and local Chinese managers working in the pig breeding industry.

Developing a joint venture involves step-by-step transfer of technology to Russia, training Russian specialists, and foreign partners' active engagement in selling the JV's genetics and supporting customers.

Creating a genetics business through such a joint venture, first in the Russian market and then in the BRICS+ countries, could both ensure payback on the investments within 5–10 years and provide the Russian partner with annual profits in the tens of millions of dollars.

Conclusion

Initiating the IPO of one or several national champions – Russian agricultural holding companies that would be large even on a global scale and capable of generating revenues in the order of USD 10 bn a year and investing tens of millions of dollars in research and development – would make it possible to take the next step: a series of transactions aimed at building world-class genetics in Russia.

Creating large agricultural holding companies through IPOs and making deals with global genetics leaders are key to building a sovereign capability in this field

Despite the slim chances of acquiring foreign, particularly Western, companies under the current circumstances, and the lengthy process of addressing issues related to IPO and finding a suitable target company, it is important to start acting towards this goal right now. Acquisitions and/or partnerships through the establishment of joint ventures with several leading foreign companies with an international standing and expertise can help achieve the strategic goal of the domestic agricultural sector – building a sovereign capability in Russian genetics – within 5–10 years. This project should be originally designed as a joint venture with other BRICS+ countries. Only the scale of the BRICS+ markets can provide the necessary economies of scale and, among other things, enable Russia to export high-tech agricultural inputs, including genetics, worth USD 0.6–1.3 bn a year.

At the same time, Russia needs to create a favorable business environment for global R&D leaders in agricultural inputs, especially for companies with BRICS shareholders. These companies should serve as both sources of valuable technologies and professional development hubs for thousands of Russian specialists who would take part in the transfer of foreign technology to Russia. As for the current R&D players, it is evident that their withdrawal from the local market will not benefit Russian genetics or the agricultural sector as a whole.

In order to send proper signals to the market, ensure the country's food security, and prevent the operational and financial degradation of Russia's agricultural sector, it would be feasible to treat international companies controlled by shareholders from the BRICS countries as "virtually Russian" in terms of import quotas for seeds and localization of their production activities in line with the government's Resolution No. 754.²⁰ It would also be advisable to establish multiple logistics channels to source high-quality seeds from countries with different geopolitical agendas. This approach guarantees that even under the most challenging sanctions scenarios, ships from a friendly country are sure to deliver tens of thousands of tons of quality assured seeds to Russian ports. In fact, this would mean that the goal of building a sovereign capability in genetic technologies has been achieved.

Primum non nocere²¹

Only the use of global cutting-edge technology will enable the Russian agricultural sector to get on equal footing with exporters from other countries in terms of competitive power and achieve the goal of increasing the exports by 1.5 times and maintaining the relatively low food prices that consumers have come to expect.

Only the use of global cuttingedge technology will enable the Russian agricultural sector to get on equal footing with exporters from other countries in terms of competitive power and achieve the goal of increasing the exports by 1.5 times and domestic production, by 25%

Through these steps, the ecosystem of the Russian agricultural sector would be able to replicate the success of Russia's digital services and equipment and create its own technology solution that would accomplish the task of ensuring national security without multi-billion-dollar investments and decades of development.

Notes

1 https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Field_Crops/cornyld.php

2 EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) – profit (loss) from sales. EBIT and EBIT margin are calculated at a sale price of RUB 35,000 per ton excluding VAT for 38% protein on an absolute dry matter basis.

3 For yields of 1.6, 2, and 2.5 t/ha, the rate of application of ammonium nitrate ranges from 70 to 200 kg/ha. For a yield of 3 t/ha, ammonium nitrate plus NPK (40:40:40), UAN, boron, urea, and magnesium sulfate are applied.

4 For a yield of 1.6 t/ha, domestic seeds at 100 kg/ha; for a yield of 2 t/ha, domestic seeds at 120 kg/ha; for yields of 2.5 and 3 t/ha, imported seeds at 140 kg/ha.

5 Other variable costs: crop protection products, wages and salaries, fuel and lubricants, outsourcing, and transportation.

6 Fixed costs: depreciation, rent, repairs, and administrative expenses.

7 Average values for corn hybrids.

8 Based on Agroexport's price bulletin dated February 2, 2024.

9 Not including 1.4 mn ha for growing corn for silage.

10 https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5423867

11 MVP (Minimum Viable Product) – a product with the minimum functional features required for operation.

12 At least two countries have approved cultivation and at least five countries have approved the import of plants with the derived trait.

13 USD 136 mn in 2008–2012.

14 Covered by the study.

15 Performance indicators of Syngenta Group companies.

16 “~” indicates that the table shows an average of several values from the same sources.

17 https://www.chinadaily.com.cn

18 Market size calculation is based on the information on revenues of leading companies and their market share provided in their public reports.

19 FCR (Food Conversion Ratio) – the ratio of 1 kg of feed converted to 1 kg of live weight.

20 http://government.ru/docs/all/147718

21 First, do no harm.