Mahatma Gandhi’s dreams are coming true

One hundred years ago, Mahatma Gandhi dreamed that one day other countries would learn fr om a free India. As we can now see, the dreams of the Father of the Indian Nation are coming true.

Last year, India celebrated the 75th anniversary of its independence. Nowadays, India is not only a great civilization with thousands of years of history – it is also a sovereign nation that will determine the future of Eurasia in the 21st century alongside China, Russia and other centers of power.

From the first days of its independence, India chose the path of non-alignment. Steering clear of the military alliances of East and West, it has pursued a policy based on its own strategic interests. This rather pragmatic approach of ‘proactive neutrality’ has paid off well so far. India is now often called the ‘voice of the Global South’. Indeed, India can speak on behalf of many developing nations as it has already made a tremendous journey that many other countries are still aspiring to. India no longer stays in the shade of the former colonial powers, it rather stands on par with them now, rejecting any attempt to impose foreign will. Given its weight on the global arena, India deserves permanent membership in the UN Security Council and Russia has consistently supported that.

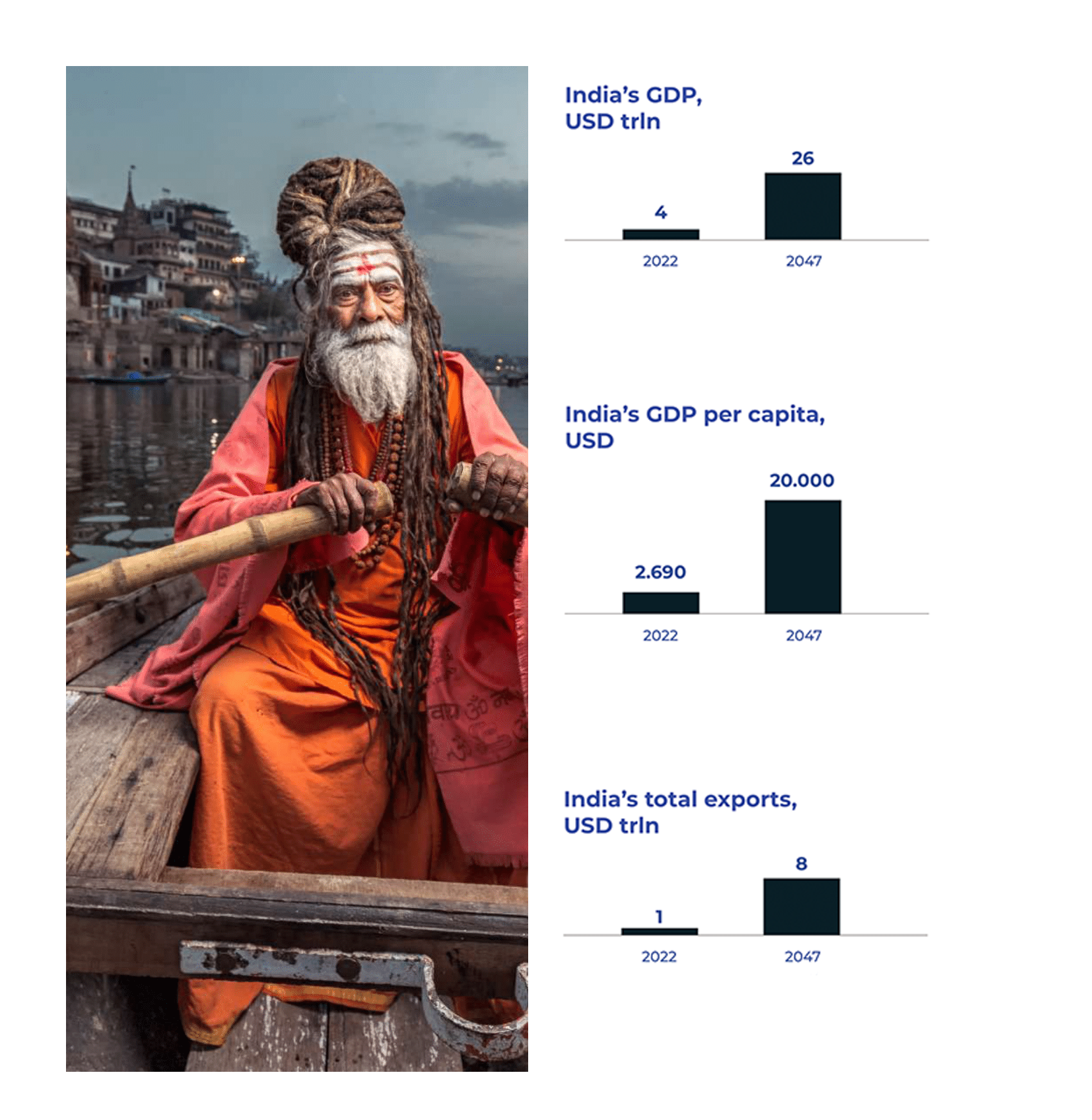

Since 1947, India’s GDP has grown by 100 times to USD 3.5 trln, while total exports increased by 500 times to USD 660 bn in the 2021–2022 financial year. Over the past 10 years, India has progressed from the 11th to the 5th largest economy in the world and continues to show impressive GDP growth (8.7% in 2021–2022). This remarkable success has not been unnoticed by other players as foreign direct investment in India grew by 143% from USD 35 bn to USD 85 bn per annum over the same period.

India is increasingly emerging as a new global economic powerhouse which should become the world’s second-largest economy by 2047, the centenary year of India’s independence. Last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi called the next 25 years ‘Amrit Kaal’ – a period in which India and its citizens should ascend to new heights of prosperity.

India has set very ambitious development goals to be achieved by 2047: it aims to become the second- largest economy globally with a GDP of USD 32 trln, growing income per capita by 10 times to USD 20,000, foreign direct investment by 12 times to USD 1 trln and exports by 12 times to USD 8 trln.

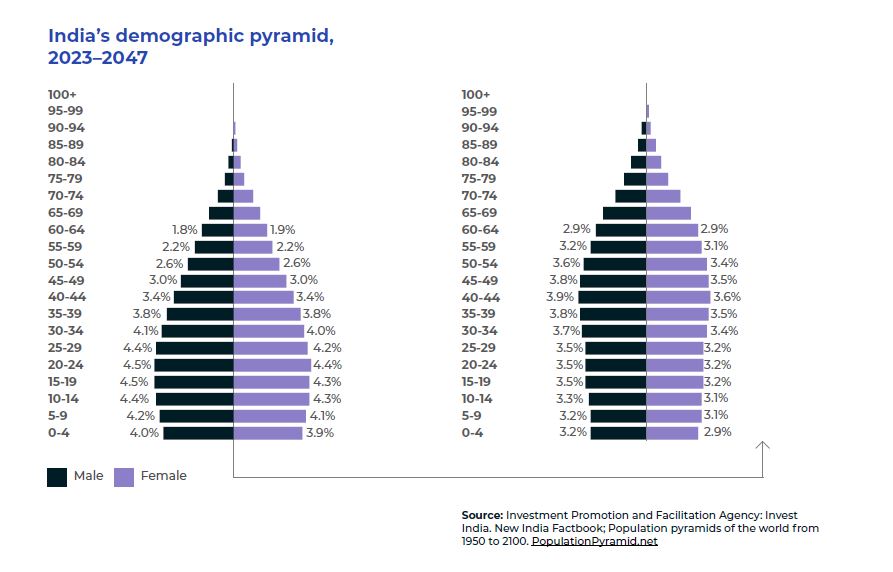

India’s development strategy should help strengthen its position as one of the global centers of power in a new polycentric world. This ambitious strategy will be dependent on industrialization and a favorable demographic situation.

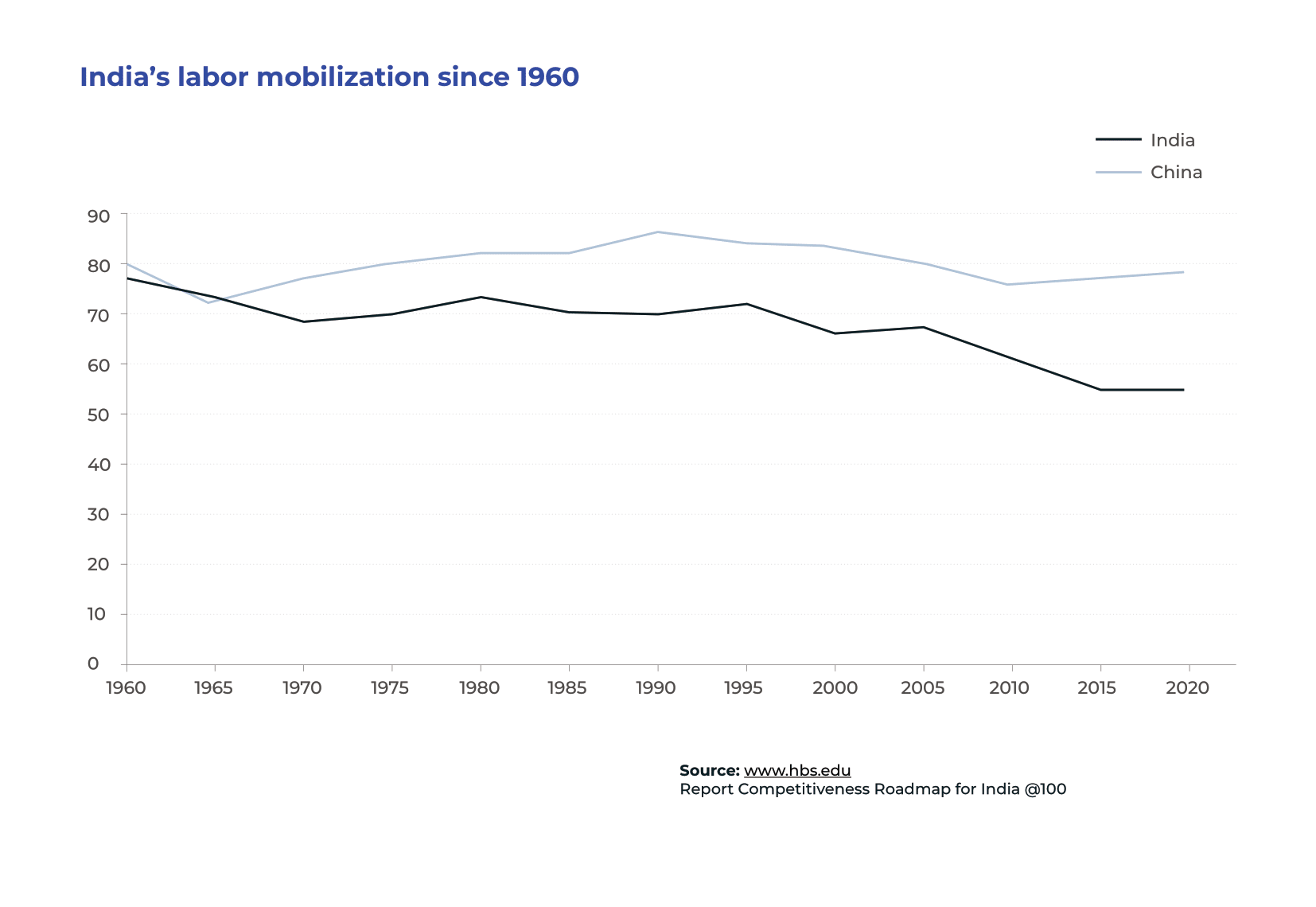

As far as demographics are concerned, the Indian labor force stands at half a billion people with a median age of 29, the second-largest and among the youngest globally. Undoubtedly, future economic growth in India will be driven to a significant extent by its young workforce, while improvement in labor mobilization will be another important driver.

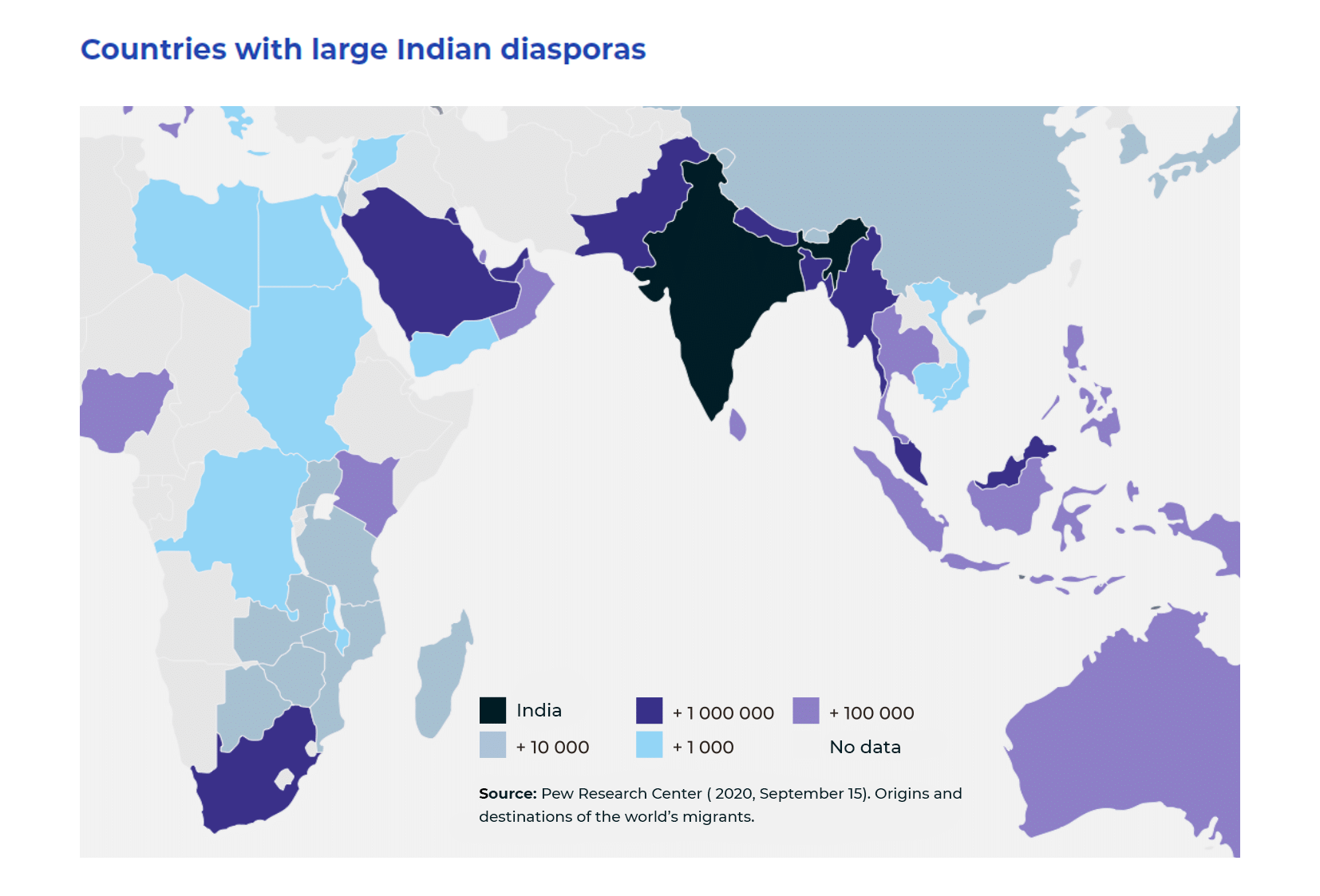

Not only the number of Indian people but also their caliber matters for the future of the economy. Indian influence in the world will be supported by its growing and prosperous diaspora, which already comprises 32 million people. No other developing nation has given to the world so many global entrepreneurs, academics and CEOs. As the diaspora keeps growing in size and influence, India’s status in the world will only rise.

India – Russia relations are built on a long history and similar values

India and Russia have a long-standing and unique history of friendly relations. Both nations share similar values in international relations and have consistently pursued independent policies, respecting each other’s interests. They also have similar views on the global developments now reshaping the new world.

The Soviet Union supported the Republic of India, respected its sovereignty from the very first days of its independence and helped it in achieving its strategic goals. That laid the foundation for decades of smooth and pragmatic relations between India and the USSR, which was later succeeded by Russia.

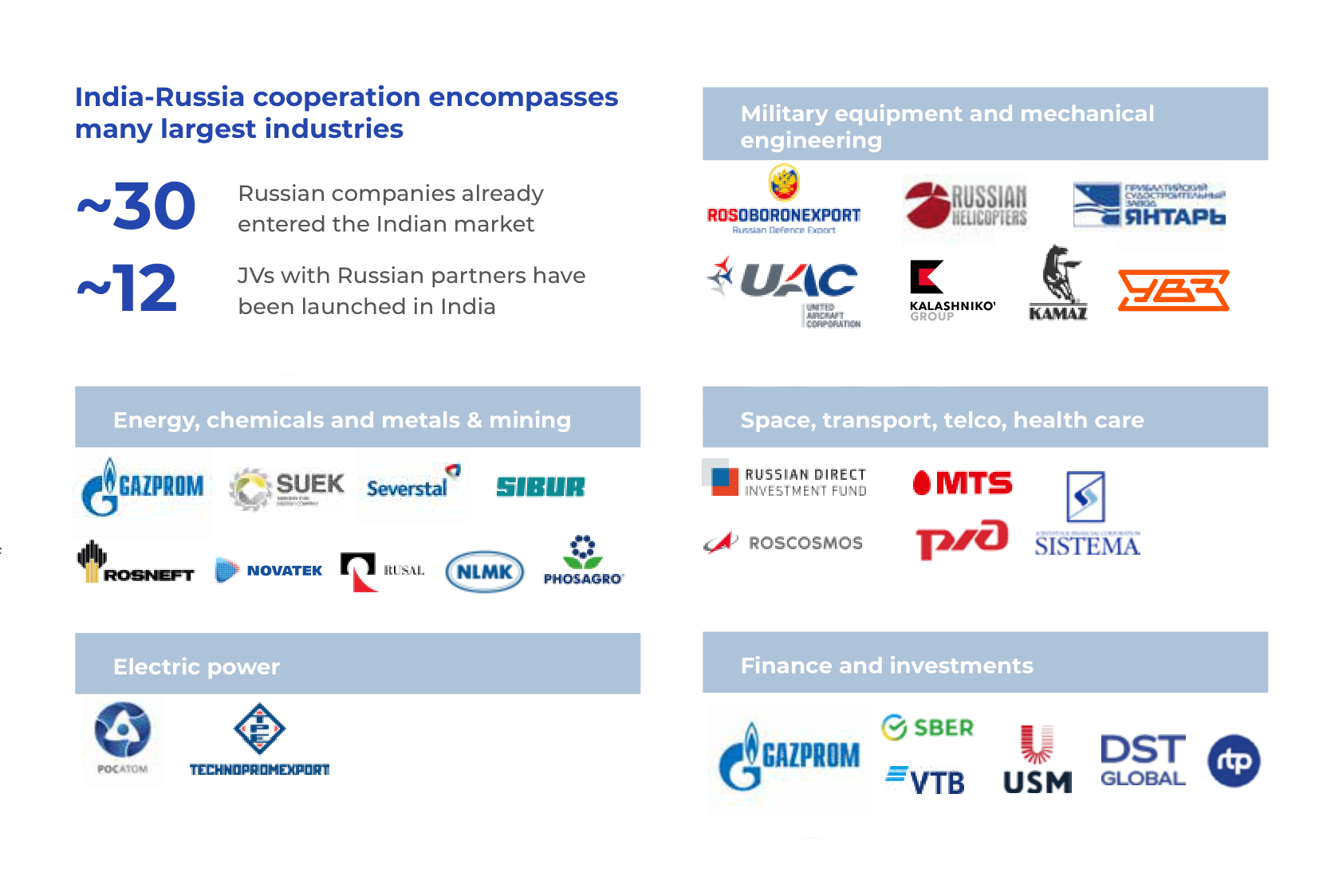

These relations resulted in cooperation across several important sectors: space, energy, the defence industry, nuclear, science, technology and health care. The first Indian astronaut Rakesh Sharma traveled to the space as part of the Soviet space programme in 1984.The USSR provided vaccines and trained Indian doctors that, to a significant extent, contributed to the development of the Indian health care system, a sizeable driver for India’s stellar population growth. In total, more than 30 Russian companies have entered the Indian market and more than 12 joint ventures with Russian companies have been launched in India. The historical relationship, geographical proximity and immense resources of India and Russia bode well for the expansion of economic cooperation. Creation of new infrastructure for that cooperation will drive the development of the entire Eurasian continent and reduce the influence of outside players.

On 31 March, Russia adopted its new Foreign Policy Concept that specifically highlighted India as a preferential strategic partner. The Concept emphasized the importance of expanding cooperation with India in all domains, including trade, investments and technology exchange. Russia is striving to transform Eurasia into a unique space of peace, stability, mutual trust, development and prosperity. Strengthening India-Russia economic partnership is an important part of that transformation.

The full upside potential of Indian-Russian cooperation goes far beyond the economic sphere, embracing energy and food security, as well as technological independence.

India – Russia cooperation to boost both economies

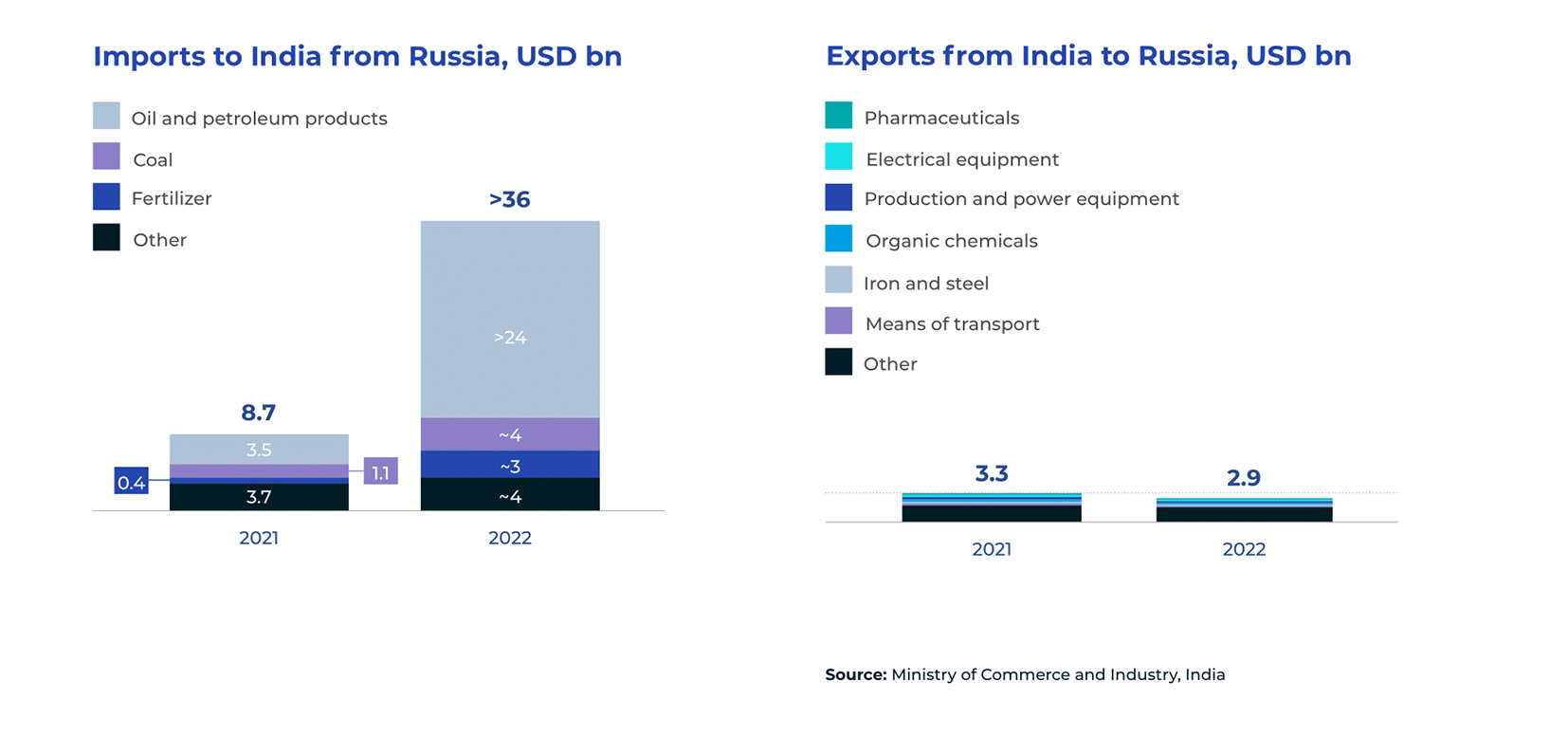

Last year, Russia’s trade flows were redirected away from the country’s historical partners in the West. This has become a significant driver for India – Russia trade volumes, which more than tripled year-on-year in 2022 to a record high of USD 39 bn from only USD 12 bn in 2021. As a result, Russia has become one of India’s top 5 trade partners for the first time, moving up from the 25th position in the previous year. There can be no doubt that the increase in trade is positive for cooperation between the two nations. However, last year’s trade volumes were largely driven by higher oil imports from Russia to India. As a result, India’s trade deficit with Russia has risen to the sizeable sum of USD 33 bn and one should expect this figure to grow further in 2023. Oil imports to India from Russia peaked in December 2022 and are unlikely to subside any time soon in the current geopolitical environment.

This dramatic growth in bilateral trade presents both an opportunity and a challenge. Given the current trade deficit, there is no doubt that India – Russia cooperation should be taken to the next level and trade should be harmonized. Hundreds of billions of Indian rupees earned by Russian exporters and held in Indian banks could be deployed for both investments in India and exports of Indian goods to Russia. We have identified several prospective areas for India – Russia cooperation that should accelerate the economic development of both countries and lay solid foundations for the creation of a single economic zone in Eurasia.

Reliable supply of resources at predictable prices to ensure energy security

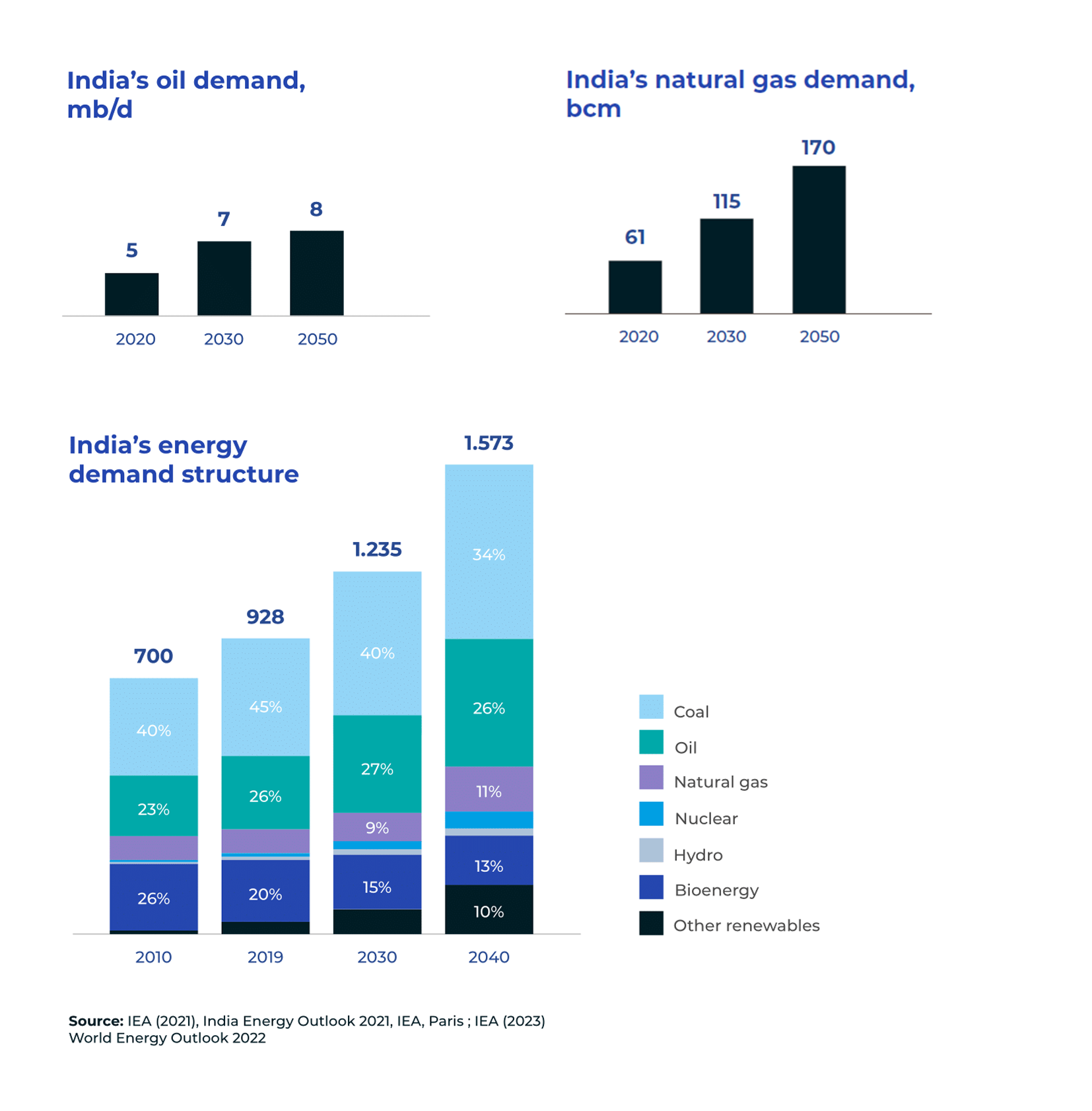

India is the world’s third-largest energy consuming country, with rising per capita income and improving living standards. Energy use has doubled since 2000, with 80% of demand still being met by coal, oil and solid biomass. On a per capita basis, India’s energy use is less than half the world average, as are other key indicators such as vehicle ownership, steel and cement output.

The IEA forecasts that India’s oil demand will increase by almost 80% from 4.7 mb/d in 2021 to 8.3 mb/d in 2050, while demand for natural gas is expected to almost triple to 170 bcm from the current 66 bcm over the same period. Russia, as a major global energy producer and exporter, is vital for India’s economic growth: reliable supplies of crude oil, petroleum products and coal from Russia could meet India’s growing energy needs.

Reliable supply of agricultural inputs to ensure food security

Energy imports matter for Indian agriculture, which is an important sector contributing close to 20% of the country’s GDP and employing more than 40% of its workforce. India is the world’s largest rice producer and a net exporter of food. It is also a major importer of agricultural inputs, such as fertilizers.

India has made tremendous progress over the last few decades in boosting food grain production and reducing malnutrition rates. Nevertheless, further growth of agricultural output remains crucial for the nation’s wellbeing as the population continues to grow. As a large producer and exporter of fertilizers, Russia can ensure fertilizer supplies to India, serving the interests of both countries.

Achieving technological independence together

Access to and localization of existing competitive Indian and Russian technologies, together with joint technological research and development could contribute to the much-needed technological independence of both countries.

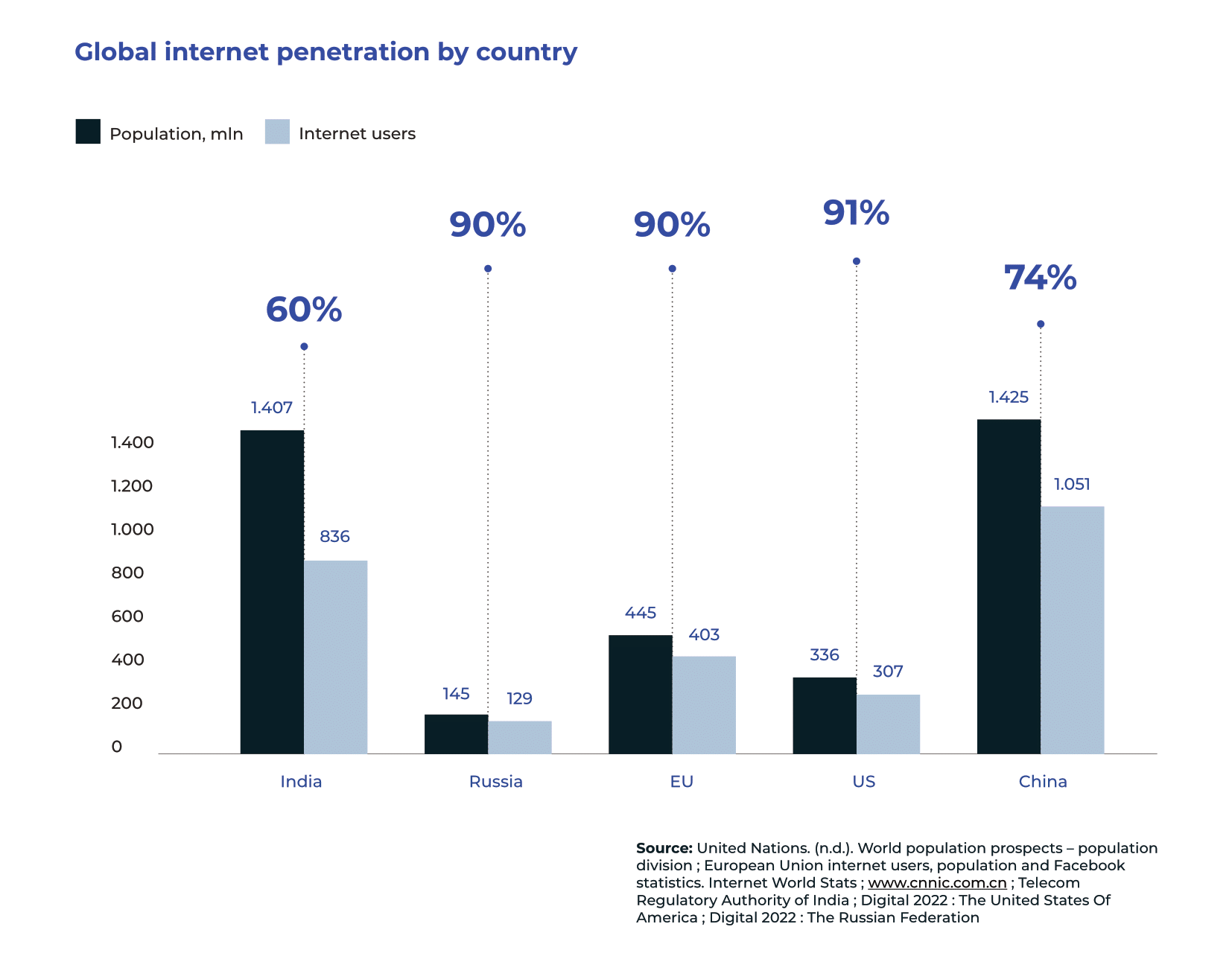

In 2015, the Indian government launched its large-scale Digital India initiative, which has turned into a transformational campaign for the entire country. Eight years on, digitalization is impacting virtually everyone in the country – 1.3 bn people in India have their own unique digital identity. India has 1.2 bn mobile phone users and 750 mln smartphone users, and is already a global leader in digital transactions.

As a result of this rapid digitalization combined with a strong enterprise culture, India currently contributes 1 out of 10 unicorn startups worldwide.

Russia has a lot to offer and also a lot to learn from India in the technological domain. Alongside India, Russia is one of only a handful of countries globally that have created their own ecosystems over the past 20–25 years (for example, Yandex, Ozon, Tinkoff, etc.). Yet Russia still remains dependent on imported hardware, making its technology sector vulnerable to geopolitical changes.

Attraction of high-quality workforce to implement investment projects of strategic importance

India is embarking on a massive program of industrialization and infrastructure building. By 2047, it aims to operate the biggest rail network in Asia and the second-biggest road network globally, while also quadrupling its port handling capacity and growing air travel sevenfold. To achieve all of this, India will increasingly need to train and mobilize large numbers of skilled specialists, especially engineers, technologists and technicians. Despite the young average age of the Indian population and workforce, labor mobilization is rather low, at 55%, down by more than 20 pp since 1960 and below China’s 80%. This could create additional challenges for the implementation of major industrial projects.

India may need to boost its educational and training capacity to achieve these transformational development targets. Since Soviet times, Russia has been a traditional destination for Indian students willing to study abroad. In the coming years, Russia could expand training and educational programs offered to Indian students in Russian universities, while also providing Russian specialists to work on largescale projects in India.

Full potential of India – Russia cooperation goes far beyond their own economies

As India and Russia are equally interested in a polycentric world, both nations can formulate new development horizons based on their strong economic potential, leading to largerscale projects beyond their bilateral cooperation. Examples of such projects are given below.

International North-South Transport Corridor to speed up Eurasian transformation

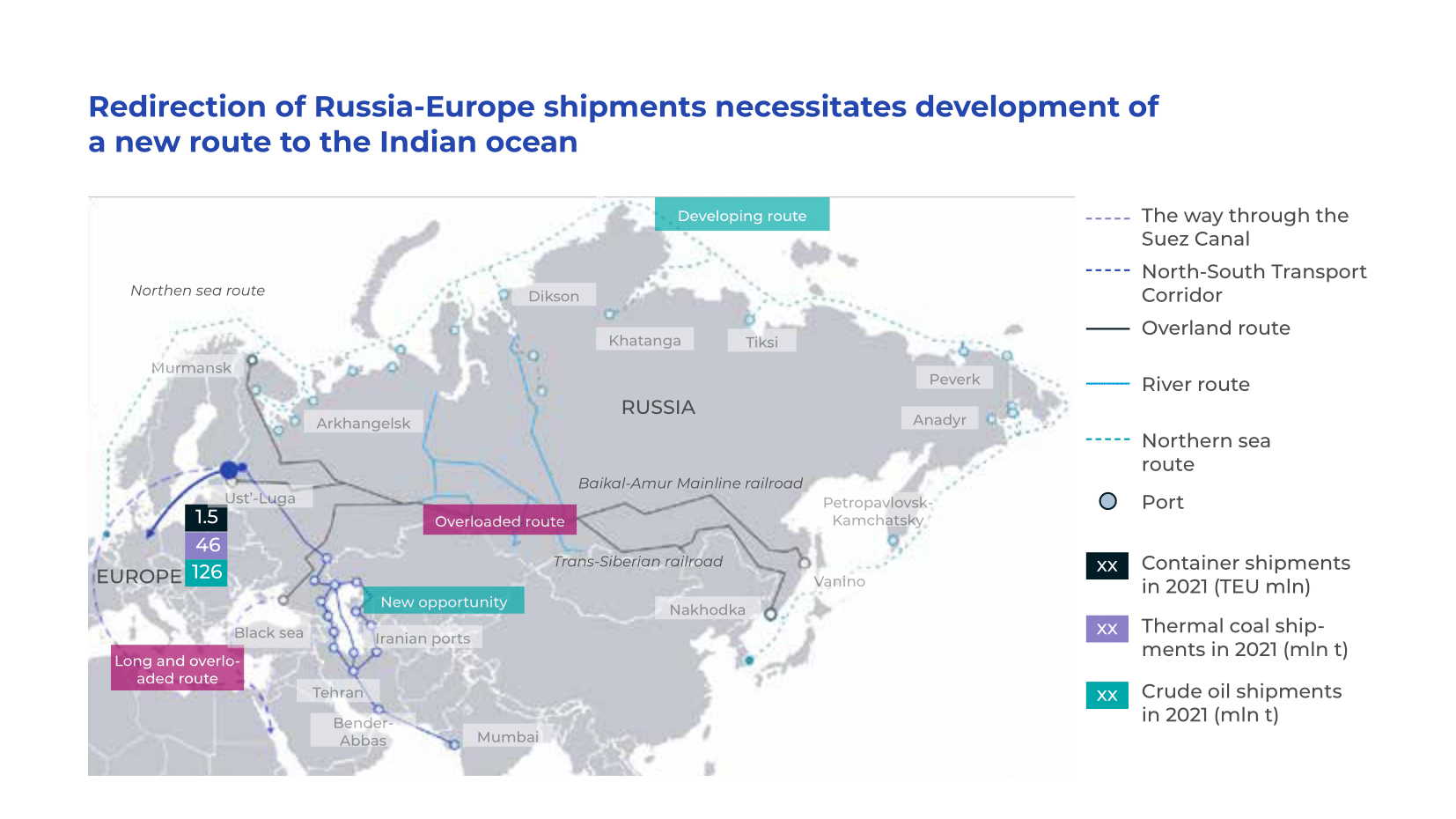

The new International North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC) was agreed upon by Russia, Iran and India in 2002. Since then, the project has not really taken off, although more than 10 other member states have joined it.

Last year’s change in Russia’s relationship with the West is lending new impetus to the NSTC. On 31 March, acceleration of the project was mentioned in Russia’s new Foreign Policy Concept as an important driver of Eurasia’s transformation into a unique economic space. The NSTC is expected to link up its member states into a single transport system which will ensure peaceful and smooth overland transit between different parts of the Eurasian continent, primarily via a high-speed railway network away from military conflict zones. The creation of this corridor will boost the economies of Eurasia and help reverse the flow of Russian resources towards the Global South.

We expect the NSTC’s cargo turnover to exceed 70 Mt by 2030 and 150 Mt by 2050. The project includes three different routes via the Caspian region. The Western Route via Azerbaijan should be developed first and will require up to USD 16 bn of investment. The Transcaspian Route via the Caspian Sea and the Eastern Route via Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan will require capex of up to USD 18 bn and USD 22 bn, respectively.

The NSCT’s economic and social benefits justify its high price tag. We expect the project to contribute USD 23 bn (1.3%) to Russia’s GDP and USD 44 bn (1.1%) to the combined GDP of India, Iran, Azerbaijan and Pakistan. It will also create 110,000 new jobs in Russia and 160,000 in the four other participating countries.

The NSTC will help reroute key Russian exports, including coal, fertilizers, chemicals, oil products, metals and agricultural products, to the countries of the Global South. In particular, the launch of the NSTC should boost shipments of Russian coking coal and fertilizers to India:

- The cost of coking coal production in Russia is about half the average cost in Australia, US and Canada. Up to 14 Mt of Russian coking coal exports could be redirected from the Japanese and South Korean markets to India, and a further 5 Mt of new volumes could be sold in India under current transportation tariffs. If a unified transportation tariff is introduced on the NSTC, Russia could add another 33 Mt and become the main supplier of coking coal to India by 2030.

- The same logic applies to fertilizers, with Russia’s production costs far below those of some other exporters to India (for example, China). Post the launch of the NSCT’s Western Route, Russia should be able to add another 6 Mt of fertilizers to the Indian market to become the dominant supplier.

The NSCT should also help to boost Indian exports to Russia. We expect northbound shipments via the NSTC to reach 1 mln TEU by 2030 and 2.7 mln TEU by 2050. These are significant volumes compared with the 4.3 mln TEU handled by all Russian ports in 2022.

New payment systems to facilitate regional trade

The trade between large countries could be done in their national currencies to decrease dependence on the Western financial infrastructure and institutions. The discord between Russia and the West has proven the need to create alternative payment and clearing mechanisms for large countries pursuing their own sovereign interests. Such independent clearing centers could be created within large international organizations (for example, BRICS) and facilitate transactions between the member countries.

Bringing partnership to third countries

India and Russia have traditionally maintained strong ties with a number of developing countries via investment, technological and scientific cooperation. Since 1961, India has been a pioneer and leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, a forum of countries that prefer not to join any major power bloc. The Soviet Union forged relationships with many non-aligned nations in Asia, Africa and Latin America, and Russia has continued this policy.

Today, joint industrial, technological and infrastructure projects in third countries wh ere India and Russia have both maintained a strong presence could become another fulcrum of bilateral cooperation. Africa, South Asia and the Middle East, in particular, would seem to be natural regions of choice for such cooperation due to their large Indian communities and historically strong ties with Indian and Russian businesses.

India – Russia cooperation may generate up to USD 200 bn

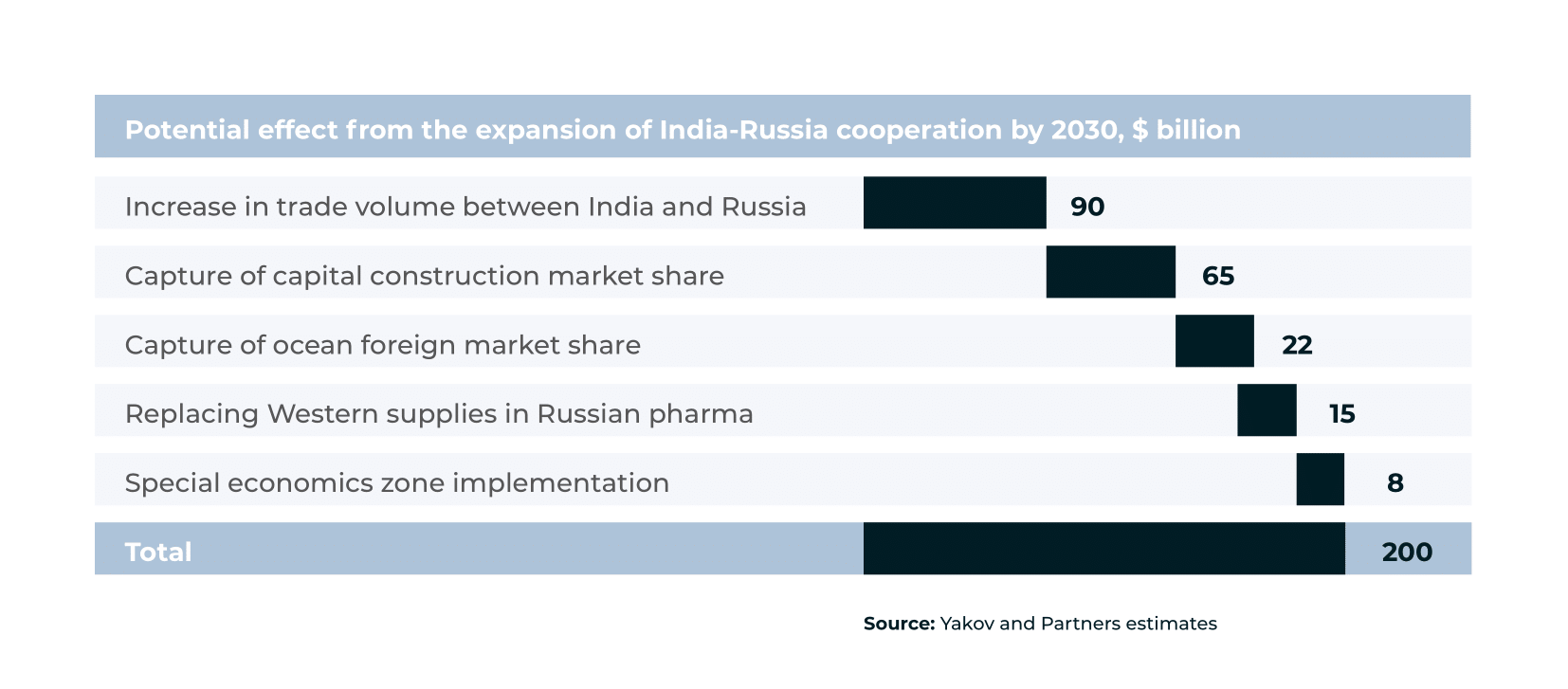

We estimate the potential impact from the expansion of India – Russia cooperation to be up to USD 200 bn of additional annual revenue by 2030, with the key growth areas detailed below.

Growth of trade between India and Russia

We estimate that trade volumes between India and Russia will generate additional USD 90 bn of revenue per annum by 2030. This will be driven mainly by higher exports of Russian crude oil, petroleum products and coal to India as Russia redirects trade flows from its traditional markets in Europe. Oil and petroleum products should be the main drivers of Russian exports as India’s oil demand is expected to grow by 40% (2 mb/d) to 7 mb/d by 2030 vs. 2020. Coking coal should be another driver as India’s total imports are expected to grow by 12% over the same period, while Russian low-cost coal can gain market share.

Joint projects in third countries

Many countries in the Middle East, Asia and Africa need to upgrade and expand their infrastructure. India and Russia could potentially capture a significant share of that market in countries with which they have strong ties (for example, the UAE, South Africa, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam and others). According to our estimates, a 20% market share could lead to around USD 60 bn of additional annual revenue by 2030.

Capture of ocean freight market share

A new Indian-Russian player in the ocean freight market could facilitate the growing trade volumes between the two countries and ease the redirection of Russian trade flows to India. Assuming that such a joint venture captures a 25% share of shipments between India and Russia, it could generate around USD 22 bn of revenue by 2030.

Replacing Western suppliers in the Russian pharma sector

We expect the Russian drug market to grow to USD 60 bn by 2030 from USD 42 bn in 2022. About 50% of all drugs currently supplied to Russia come from Western countries. Last year, more than 10 Western drug producers announced the termination of their clinical trials in Russia, potentially resulting in a shortage of innovative original drugs in the medium-tolong term. In addition, most of those producers have also stopped investing in marketing and promotion, which could lead to the complete withdrawal of their drugs from the Russian market.

India is a leader in the global pharmaceutical industry, with a 20% share of exports of generic medicines. Drug exports from India have grown by 103% between 2014 and 2022. As India’s pharmaceutical industry is expected to double its revenue to USD 130 bn by 2030, we see significant opportunities for India in the Russian market as Western players withdraw. Taking a 25% share of the Russian market (about half of the Western companies’ share) could generate around USD 15 bn of revenue for Indian companies by 2030.

Transfer of manufacturing capacity and technology to India

India is experiencing rapid industrialisation and Russia can contribute to that via setting up production facilities that would target both the Indian domestic market and exports. It would benefit many industries in India facing shortage of capacity currently and expecting significant demand growth in future: shipbuilding, power generation, railway machinery, chemicals and fertilizers, steel and other areas. It would create a reliable supply of products to the growing Indian market and localize technologies. As an example, combining several production units from the above sectors in one special economic zone may have a potential positive impact of around USD 8 bn of sales per annum.

Action plan to capture the cooperation potential

We outline below a number of practical steps that could help India and Russia fulfill the potential of their long-term cooperation.

- Facilitate the bilateral trade in Indian rupees and Russian roubles to decrease dependence on the Western financial infrastructure.

- Introduction of incentives for Indian companies to participate in the development of the International North-South Transport Corridor.

- Creation of a strategic alliance to jointly implement infrastructure projects, targeting markets in which India or Russia have had a strong historical presence (for example, Africa, the Middle East, South and South-East Asia).

- Creation of a new logistical operator to securely handle the growing volumes of resources and goods traded between India and Russia.

- Agreement on drug certification with Russia to boost exports of Indian medicines and replace the high share of Western medicines in the Russian pharmaceuticals market.

- Development of incentives for Russian companies to transfer manufacturing of goods in the later stages of the value chain to India.