Last year was a challenging one for this country, affecting every industry without exception. A new study by Yakov & Partners has found the voluntary sector in Russia has basically switched to a "survival mode". Infrastructure funds now tend to focus on statutory activities rather than take on new projects or develop new areas of work. Major funds providing targeted assistance are pivoting towards basic assistance to those in most need, while mid-sized and smaller funds are struggling to survive and retain their employees.

According to the study carried out last December, charitable donations in Russia dramatically decreased in 2022 as donors cut back on giving to charity, disposable household incomes declined, cross-border inflows ebbed, while the expenses of charitable organizations increased.

Although this may be a temporary situation, the Russian charitable sector is unlikely to return to the way it was before due to the changing society needs. For instance, environmental issues are being superseded by more pressing problems, such as assistance to and rehabilitation of the disabled. This is why it is crucial that charitable giving should remain high on the agenda, as concern for others and readiness to help shape the society we will live in.

The new reality

One of the main factors now affecting this sphere is the ever-increasing atomization of society. In a recent poll we conducted jointly with Romir Holding, more than half of the respondents (53%) admitted that their mental state had deteriorated, while 21% had seen their relations with family and friends go sour. This makes people less inclined to reach out and offer a helping hand, especially when it comes to strangers, compelling them instead to care more about their inner circle rather than broader society. Once you add in the "attrition" of active citizens who used to give generously to charity and contribute to the organization of the process itself, it is safe to say that this sphere is facing problems of an unprecedented scope.

Yet, despite a drop in donations fr om those donors who have left Russia, the average amount of one-time and recurring donations from private donors increased by more than 5% in 2022. While this is not enough to offset even the increase in inflation, it signals that charity providers who remain in the country are still willing to support local organizations. The greatest increase in the share of donors was observed in the categories related to the events of 2022 – aid to victims of disasters and military conflicts (+33%), migrants and refugees (+200%) – though admittedly it could be partially chalked up to a lower baseline in these areas in the previous years. The share of non-financial targeted aid soared last year: every second donor handed over various items, including clothing and hygiene products, to reception centers, while every third donor provided targeted aid to specific people. Other categories to which support had migrated, included children with disabilities and children in need of medical treatment (+15.4%).

What’s in store for the sector?

Under the circumstances, one of the viable solutions could be to switch from the financial model habitually applied in Russia to the resource model as is practiced in China and India. Corporate social activity may well transition from a "let's do something nice because it makes us look good" modus operandi to a normal business practice with clear metrics, performance management tools, and sound operational management, which has often been lacking until now. This means that social responsibility programs and corresponding budgets of Russian companies could be used with greater efficiency.

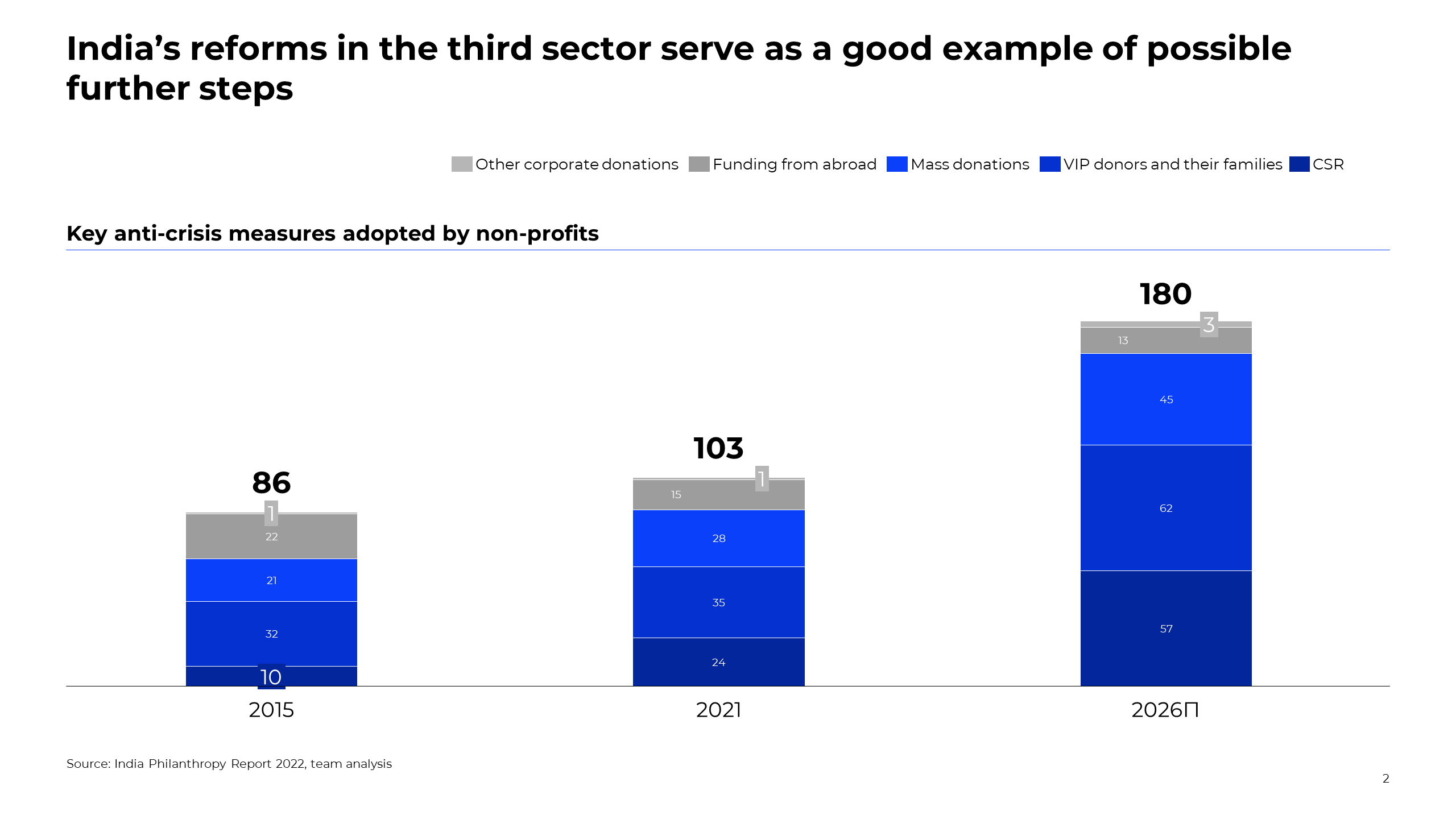

For example, in India, 70% of corporate social responsibility (CSR) donations are channeled into healthcare, education, regional development, environment, poverty alleviation, and disaster relief. It bears noting that this is the only country in the world wh ere CSR provisions are mandatory. Companies with a net profit of at least 50 million rupees are required to pay a minimum of 2% of their average net profit over a period of three years to support one area of CSR at their discretion. Corporate contributions allow the government to cover a broader range of areas, and donation volumes are expected to increase by more than 70% by 2026. All in all, India's experience proves that corporate philanthropy can be made highly effective through a set of transparent and sensible rules.

The role of the state

Although state support for the voluntary sector would be extremely helpful given the difficulties with corporate charitable giving, allocating additional funds in the current environment might prove problematic. But even without federal or regional allocations, there are quite a few things the government could do to help right now. One such example would be passing of the disability bills. Public organizations have long pushed for a law allowing distributed custody for legally incapable or partially incapacitated citizens. The State Duma approved the bill in first reading in 2016, but has yet to pass it in second reading. The state could also accelerate the allocation of funds for prosthetics, so that those in need could receive them faster.

In view of this, the optimum solution would be to merge the isolated elements of state support into a single system and integrated "customer journeys". Those journeys should consist of multiple elements and last at least 1.5–2 years in order to retain a fully socialized member of society and ensure that the necessary means of rehabilitation are provided in full during the first weeks following incapacitation. Today, unfortunately, in order to receive support, one has to overcome the bureaucratic obstacles on their own, losing precious time and faith in social institutions. But this could be put right if infrastructure funds join forces with businesses and consulting companies to act as intermediaries, lobby for legislative initiatives, and drive the development of this sector.

Looking for a solution

In times of crisis, organizations are not infrequently forced to switch to an emergency mode when they work hard to reduce operating costs, take fewer risks, and cut off investments into development. After that, they find it hard to get back on track and resume doing what made them leaders in the first place. This is also true for the charitable sector. So, right now the top priority for charitable organizations will be to do all they can to retain their key experts whom they have been handpicking for years and who will be difficult to re-engage in this sector.

Another task is to analyze current processes and find ways to maximize their performance. Before the crisis, some professionals, for example, psychologists working in children’s homes, would spend less than 50% of their time working directly with patients. This is no longer good enough, so it is important to make sure that such employees devote at least 80% of their time to working directly with children.

Yet another task is to assess whether the available set of aid instruments is still relevant amid the increasing atomization of society and growing demand for certain types of charity, or if it needs adjusting.

Many charitable organizations still handle large sets of programs. Those should be trimmed down to include only critical programs; another option is to change their footprint or consolidate them. For example, if several funds in different regions specialize on similar problems, they could try and join their forces after deciding on a methodology. That way, they could capture some positive results due to economies of scale without losing their "specialization". As our December study showed, major foundations providing targeted assistance could start consolidating the efforts and resources of smaller charities (including regional organizations) and directing the funds of corporate foundations to alleviate the most acute problems.

This way, the landscape of the Russian charitable sector could shift from competition to collaboration, which, in turn, could help unite society in the new reality. Such an approach would be extremely relevant, because in charity, unlike other sectors of the economy, an increase in the number of market players usually leads to lower efficiency of individual organizations.

Among the new players, there are a number of organizations that got "spontaneously" involved in supporting refugees. They tend to focus on horizontal connections, which helps them marshal the resources more effectively. However, at the moment the process is disorganized and leaves out conventional charitable institutions, which can undermine the results.

In the current crisis the mechanisms of providing targeted support remain as finely tuned as ever, because those organizations which have long been active in the market know all the ins and outs of this segment. Due to lack of resources, charitable organizations are now facing a difficult and rather unpleasant choice. They can either distribute the available amount of aid among the same circle of people they used to help, thus reducing the level of support for individual beneficiaries, or restructure their programs to provide the same level of support to fewer people. Under the circumstances, charitable organizations will be forced to make tough decisions. However, it is possible to overcome the crisis through concerted and purposeful efforts of non-profits, businesses, and the state. This, in turn, could help answer the question that has been looming large over our society: how to bring oneself to care about the problems and sufferings of others at a time when the country is undergoing such sweeping changes.

For more detailed findings please see the presentation.