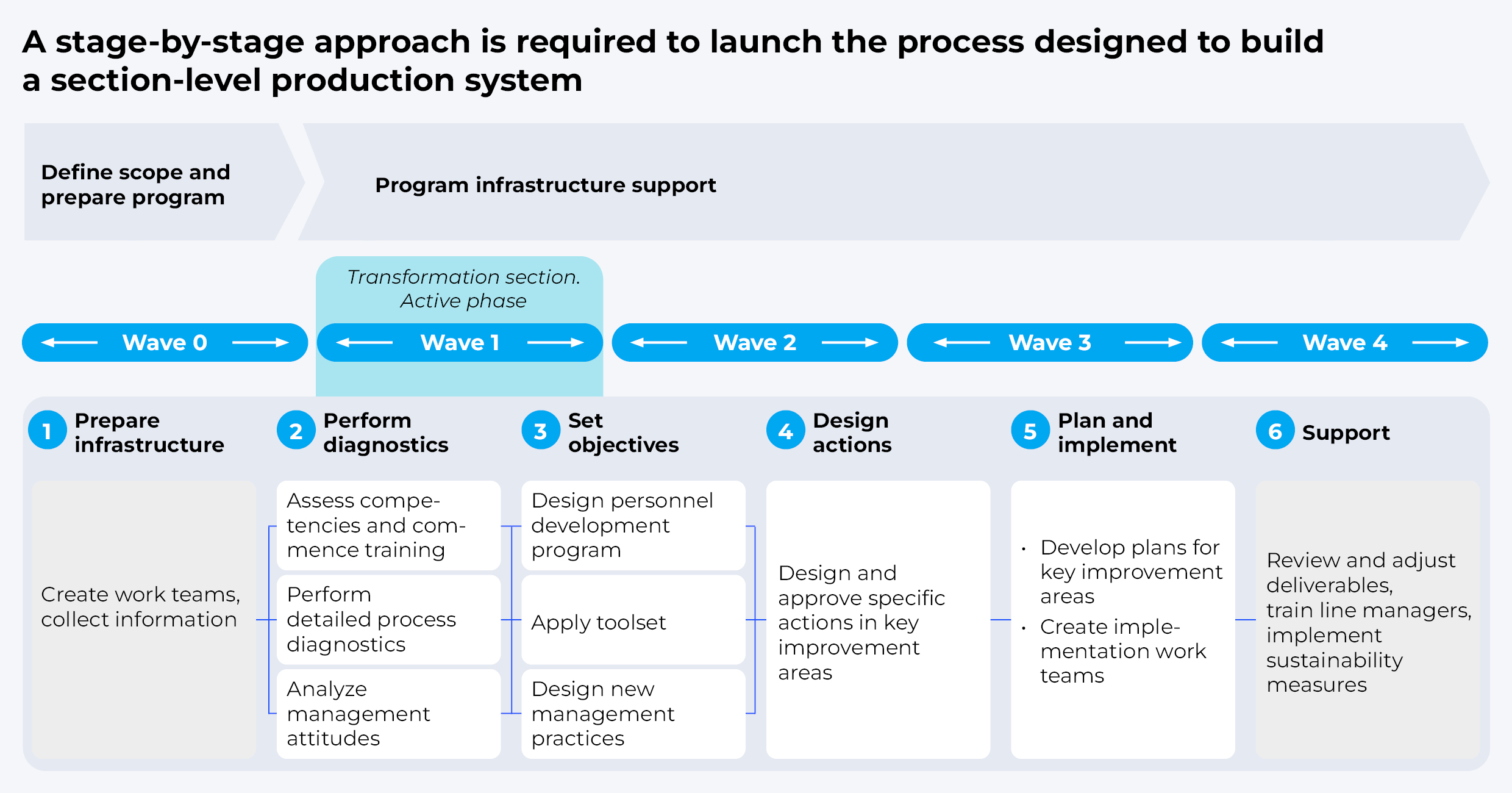

Today, almost every business is confronted with sweeping changes in their production chains. Far-sighted leaders are beginning to reevaluate their strategies. But introducing large-scale changes simultaneously across the entire organization could set you up for failure. That is why any large transformation program implemented by the Big Three consulting companies is traditionally carried out in waves, or stages. The zero wave includes a session where top managers align their positions on critical issues, such as:

— Why do we actually need a transformation?

— How do we set priorities at the start?

— How do we set up a program office and get all other employees on board?

Typically, consultants participate in three to four transformation waves, which can progress fr om function to function, fr om asset to asset, or from core to support processes. Any change starts with stating the fundamental questions, discussing how to look at the business as a whole, and often a preliminary diagnostic.

Transformation itself can take from several months to several years, depending on the size of a business and the ambitions of its CEO. The most successful tech players turn transformations into a continuous business improvement process. This could be best illustrated by Apple or Yandex – the latter evolved from an Internet search engine to an entire ecosystem of digital services within 25 years.

Like an entire program, each wave includes a set of traditional stages: diagnostic, goal setting, and initiative development. This is followed by planning, implementation, and support stage, which often takes as long as the active phase.

The first and most important step in any program, however, is the first stage, that is diagnostic. In everyday terms, it is a lot like visiting a GP. A patient notices alarming symptoms or, on the contrary, wants to build up strength and stamina, and goes to the doctor. Together, they come up with a treatment or exercise plan and monitor the effect.

Running Organization Diagnostics

Basic Tools At the diagnostic stage, companies resort to three key tools.

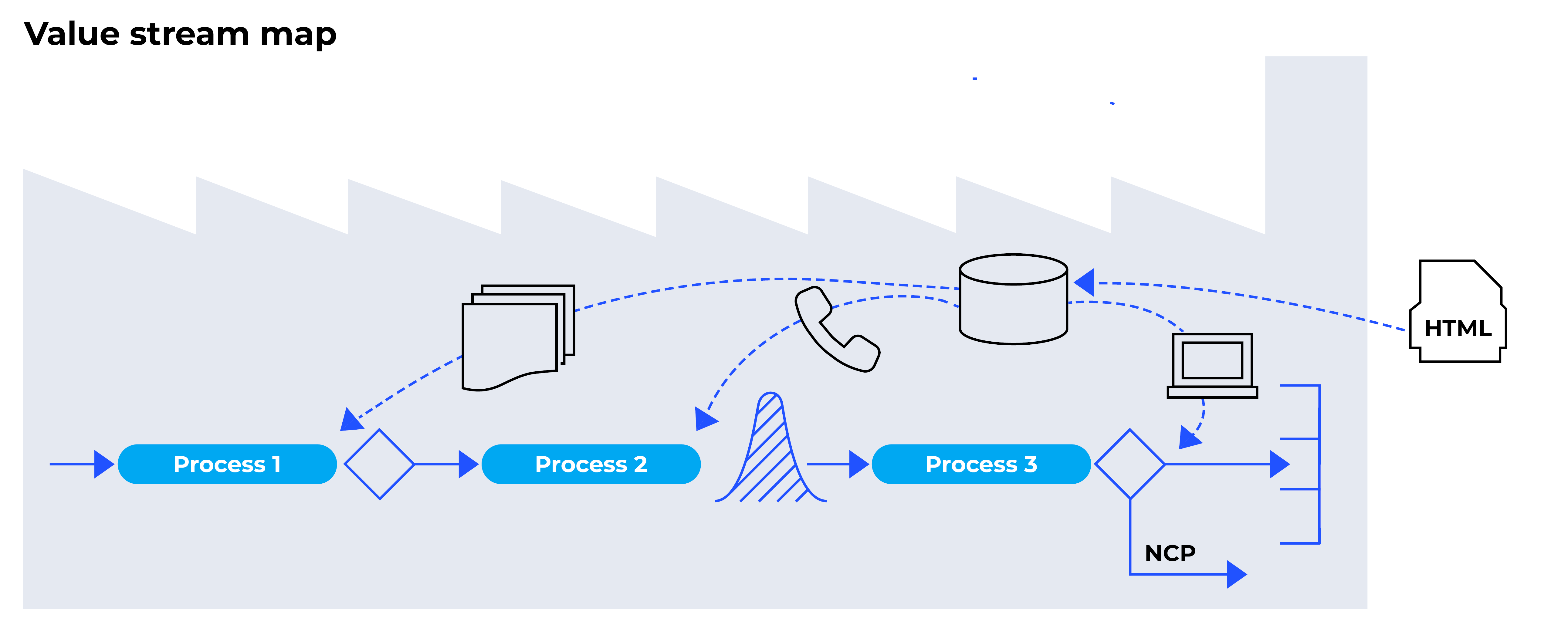

1. Value Stream Map

Helps visualize and better understand the business and identify process bottlenecks.

Bringing together leaders from different levels and functions is a good way to thoroughly understand how the business is structured and set about creating a “to-be” vision. A value stream map is usually designed by business unit leaders in a “criss cross” fashion, with each expert examining how one process outside their sphere of competence is arranged. They identify bottlenecks in the process and prioritize them.

Traditionally, leaders tend to be close to the Gemba (process points) during the mapping exercise. However, it can also be done remotely. This is important for large companies with remote assets and locations. In this case, it is advisable to appoint a facilitator capable of translating process knowledge into a diagram, i. e. into a single chain. This is how we coordinated stream mapping efforts between employees of an oil company operating a pipeline and a loading terminal.

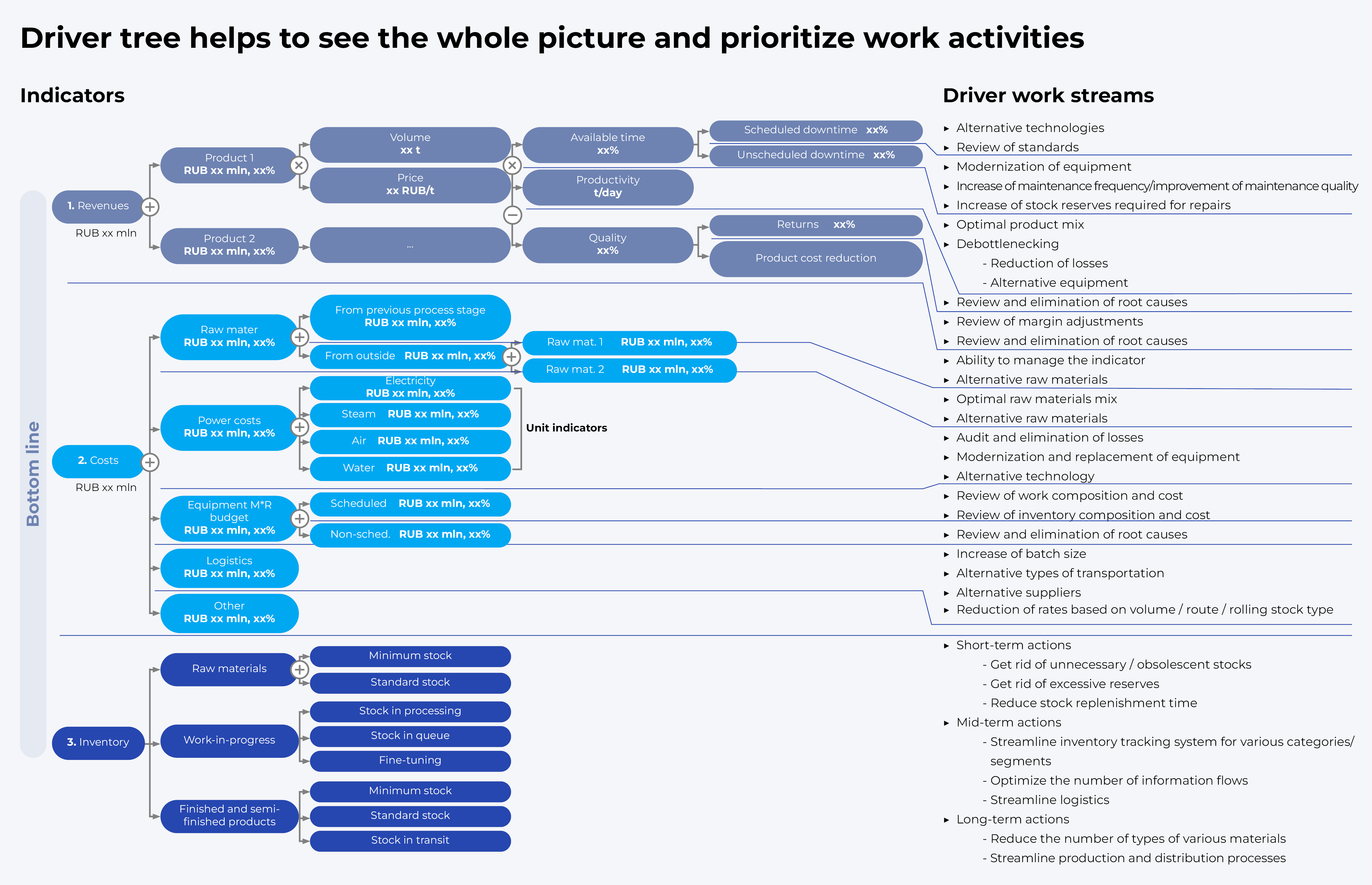

2. Driver Tree

Helps visualize BU economics and assess impact of specific factors and processes on its general performance.

A driver tree usually starts with a financial indicator of the BU, e. g. profitability. This indicator is then broken down into production, costs, and inventories. In this way, we drill down on all aspects of the operations, going as deep as drivers at the level of individual processes, such as downtime of key equipment, staffing levels, cost of inventory in the warehouse, etc.

Driver trees help to build up the big picture and the logic behind the business organization. Apart from that, they can serve to create a coherent system of KPIs: just map out key responsibilities of each function and conflicting indicators. We conducted a four-week diagnostic of a metallurgical plant. In each shop, the number of potential initiatives indicated on the map and on the driver tree ranged from 50 to 100. Not all assumptions made at the diagnostic stage evolved into fully-fledged initiatives. Yet, at the initial stage the approach we used to tackle the identified problems was "the more, the better".

3. The “Voice of the Customer”, or Kano Model

Helps analyze the real needs of internal and external customers.

Looking into the needs of core business process customers could help organizations shape the expectations regarding quality levels, product specifications, timelines for service delivery, granularity of required information, and other costly aspects of operations. Sometimes companies may discover they tend to gold-plate, which makes their products difficult to market, or on the contrary, they fail to meet customer quality requirements. Both undoubtedly are fraught with hidden wastes. During one transformation program, experts found that giving feedback to the internal customer in the lab, as well as specifying the exact location of materials in the warehouse, allow for more efficient fine-tuning of processes down the line.

The three key tools provide a lot of leeway for companies to examine BU performance.

Approaches to Unlock Hidden Potential

A variety of approaches could be used to shape a holistic view of a business and unlock its hidden potential.

1. Internal benchmarking against best indicators (historical data) — wh ere we were six months ago / last week / during last shift.

If you compare instances when performance was below average with those when it clearly exceeded expectations, you may come up with interesting conclusions and develop new initiatives. However, you should not rely on internal benchmarks alone. Findings extrapolated fr om previous experience should not be applied to situations that your company has never been in before. For example, it would be wrong to scale up the experience of a successful week without analyzing the factors that were conducive to those great results.

2. Brainstorming in focus groups.

There are different formats for brainstorming, but one of them, the collision workshop, may prove the most effective. The moderator divides the brainstormers into two groups and gives each the same task. When it is solved, the participants compare the lists of solutions, discuss the results, and critique each other's ideas. Thus, best solutions get top priority right from the start.

3. Bottleneck analysis for key processes.

Process owners and technical experts verify equipment capabilities, especially in process bottlenecks. They ask the following questions:

— What is the actual technical lim it of key processes?

— Has it been reached, or is there still room for development?

— What if the processes undergo a major overhaul?

4. Benchmarking against high-performing industry players and search for new ideas.

Due to a variety of constraints, it is not a question of visiting all the most efficient companies in the industry, but rather of learning from their experience. It is better to choose companies similar to yours to study. Tread cautiously, though. If the team relies too much on benchmarking, you might get hung up on what your competitors are doing and lose focus on the uniqueness of your own customer processes.

5. Visits to other company sites and other companies.

Executives often ask consultants to help them learn from other companies, suggest what companies they could visit, and wh ere to get new ideas. They visit companies that produce an entirely different product, provide an entirely different service, or are located in a different geography. That way, best solutions and practices migrate fr om one industry and geography to another. Quite often this brings significant economic effect.

For instance, a team of executives from a Russian-based company spent a week studying companies from a variety of segments, including heavy machinery, electronics, and paper manufacturers. Each inspired a host of ideas related to better work organization and visual management, predictive maintenance and repair (MRO), and so on. The ideas were later presented to the company president and put to good use.

6. Revisiting forgotten ideas.

This aspect of analysis is particularly beneficial for large companies with a long history. More often than not, companies have whole layers of data, developments, and solutions that never reach the point wh ere they could deliver value, and with time are lost altogether. As former Siemens CEO Heinrich von Pierer famously noted: “If Siemens only knew what Siemens knows, then our numbers would be better”.

That is why generation of initiatives during an efficient transformation program can and should come in a variety of genres and formats that will complement each other.

In Search of Ways to Improve Organizational Effectiveness

Apart fr om diagnostics, many managers would like to look at their organization as a holistic organism and gauge its well-being through more general methods of assessment. Here we will review two methods with a long history of use.

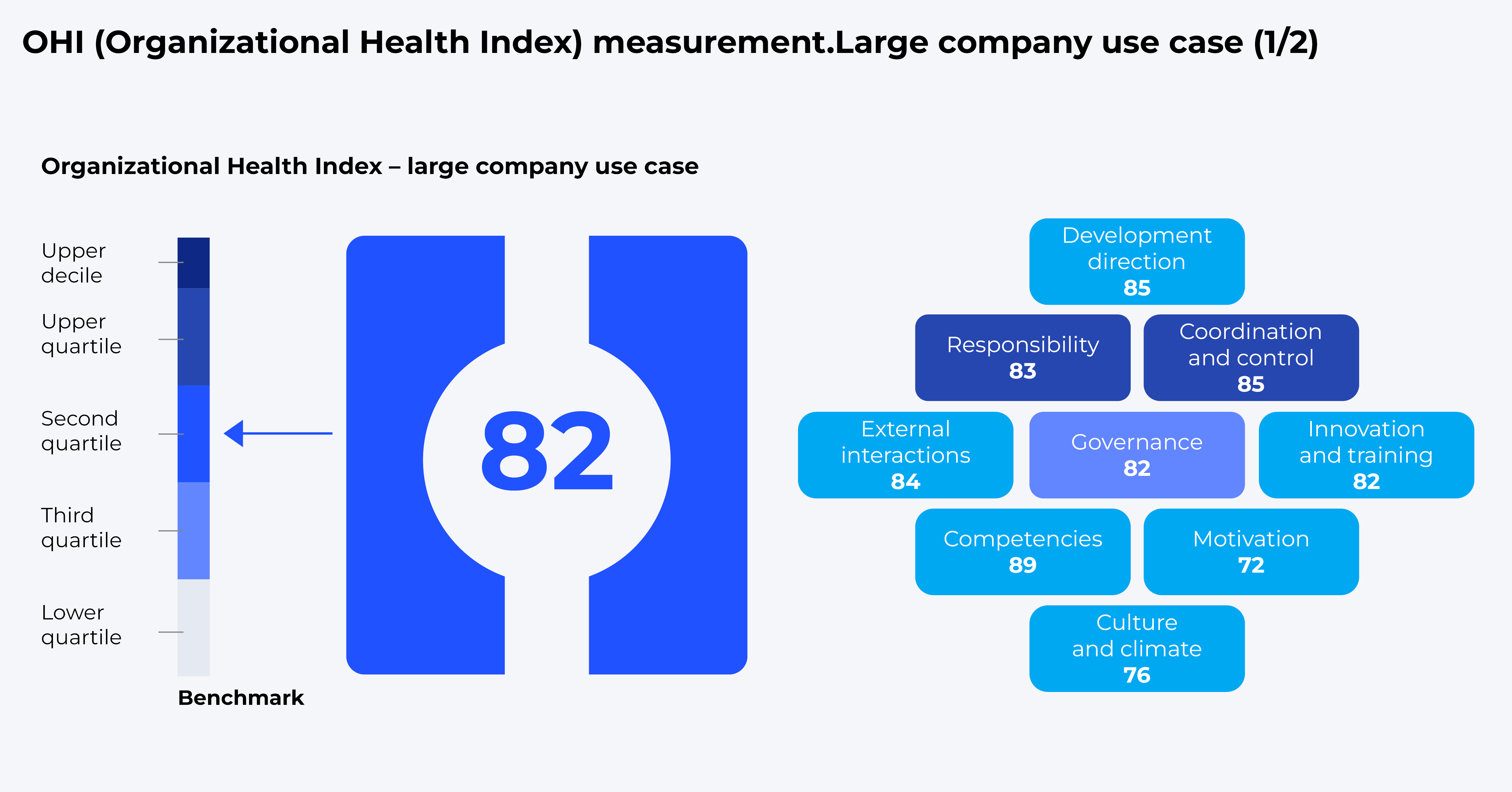

1. Organizational Health Index.

The Organizational Health Index (OHI) has been in use for a relatively short time (about 8 to 10 years), yet has proven reliable many times since. It is based on comparing a company's measurement results with those of other industry leaders.

In order to assess overall company performance, experts survey employees on issues across 37 practices, that are grouped into nine larger blocks. The survey covers employees at all levels, from frontline to the CEO. Experts sum up all the answers and compare the score to other companies in the industry. To get a reliable result, it is necessary to collect opinions of about 90% of employees. In large companies or their divisions, it could be thousands of people, so the analysis may take from one and a half to two months.

Next, workshops are held in each BU that participated in the survey. These usually take a full day to complete and help leadership and their teams learn a lot about their own organization. At the same time, executives begin to think of ways to solve the problems identified. At one company, the leadership believed sustaining an open dialogue about problems was enough. However, during the workshops, they came to the conclusion that it was necessary to appoint a person responsible for solving each problem and to monitor the results. Otherwise, no tangible effect could be achieved.

There is a direct correlation between a company’s organizational health index and performance. That is why measuring the OHI calibrated against the results of thousands of real companies helps organizations secure long-term growth and success, including capitalization growth. Healthy organizations move faster, they are more agile and dynamic, and ultimately more profitable.

2. Operational Excellence Index.

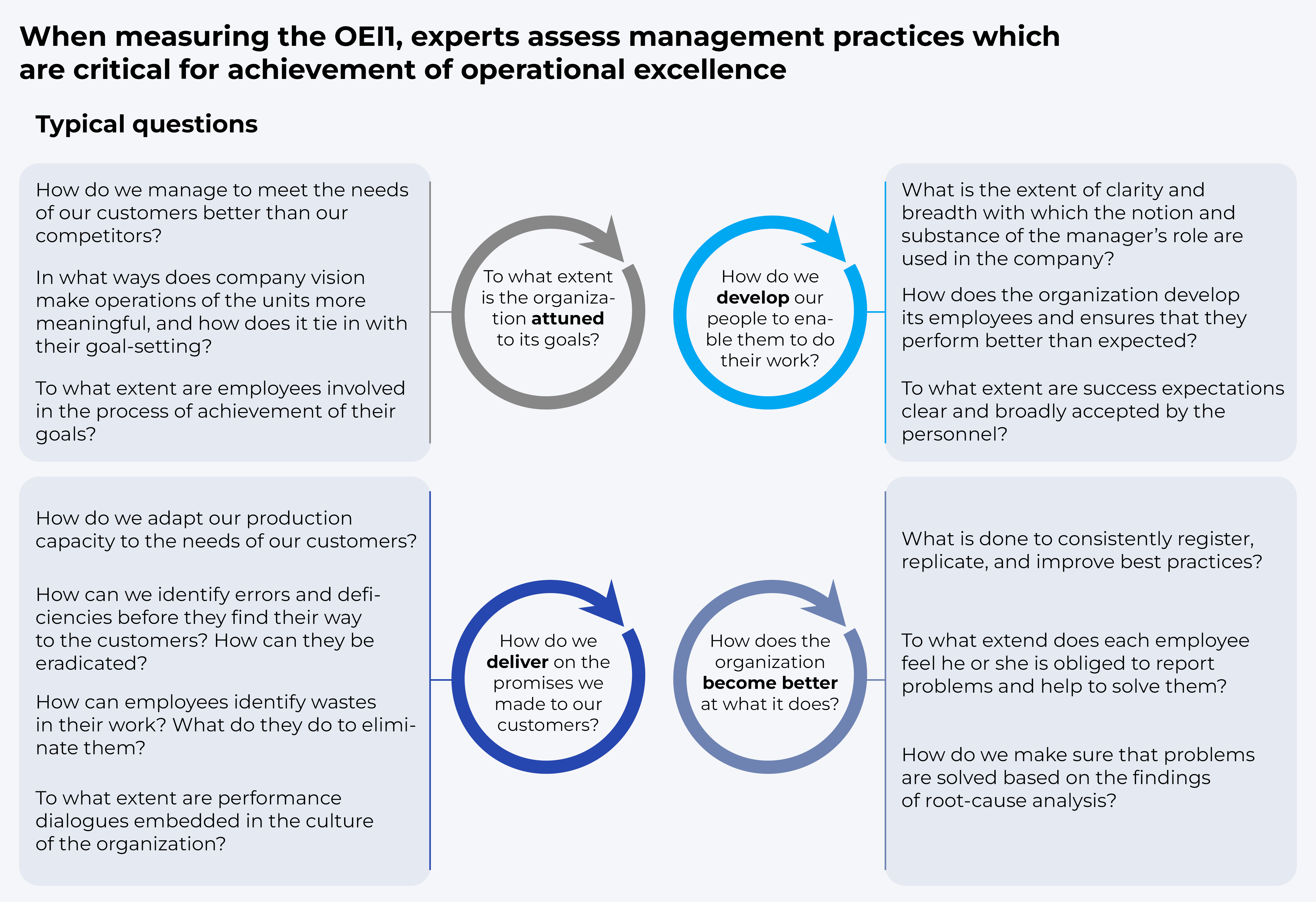

The Operational Excellence Index (OEI) allows a more technocratic look at the organization, than the OHI. It helps assess process efficiency, employees’ ability to improve them, and the management’s readiness to invest in the company development. The index includes four elements. Two of them look at “immediate” efficiency, i. e. satisfaction of clients' needs. The other two are more forward-looking and deal with future development of the company.

The first set of questions pertains to the organization’s commitment to achieving its goals. The other deals with how it ensures fulfillment of its obligations. Typical questions to be answered within these assessments are as follows:

— How do we meet the needs of our customers?

— How are we better than our competitors?

— To what extent are employees involved in the achievement of our common goals?

The last question entails another, much more difficult question: "Do employees know about their own goals and how to achieve them?"

The next two sets of questions seek to find out how the company develops people to do their jobs effectively and how the employees get better at what they do. Typical questions here are as follows:

— Who is the head of the company and what is their role in the company?

— How does the organization develop its employees and ensure that they are productive?

The improvement block deals with the following questions:

— Wh ere do our best practices come from, how do we replicate them?

— How do we make sure that employees both solve problems and analyze the root causes?

— How do we correct and learn from our mistakes?

It usually takes a few days at a manufacturing facility or an office in case of a non-manufacturing organization to gauge those metrics, and two or three experts to put the results together. In a week and a half, a company can learn a lot about its operating system. Production system experts might pick up on certain similarities between the OEI assessment and the Shingo Prize, which is valued in the business world about as much as the Oscars are in the film industry. In a way, that is exactly so. The criteria are similar, but the OEI is more geared towards quick development of improvement measures.